Origin of the Great War - 1918

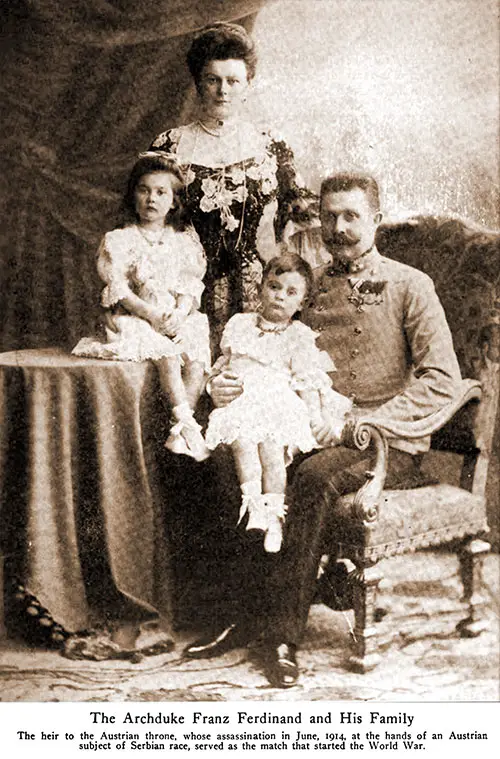

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and His Family. The Heir to the Austrian Throne, Whose Assassination in June 1914 at the Hands of an Austrian Subject of Serbian Race, Served as the Match That Started the World War. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 1: The Great Explosion, 1920. GGA Image ID # 197e7a0700

The greatest war in history resulted from Germany's claim to dominate the world and the inevitable resistance, which such a pretension excited. Visions of an Empire, transcending the power of a Louis XIV or a Napoleon, had long dazzled the eyes of William II., the German Emperor, and the German military class.

The merchants and manufacturers, intoxicated by their increasing success in commerce and industry, shared in the illusion of their rulers.

For more than forty years, Germany's claims had divided Europe into hostile camps. Each continental nation was armed to the teeth; every accidental dispute became dangerous because it might provoke an internecine conflict.

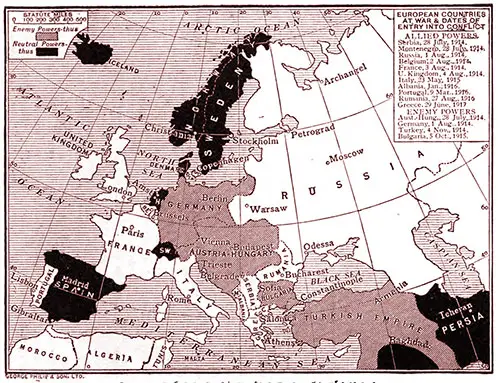

On the one side stood the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers, Germany, Austria, and Italy, which latter State was, however, becoming conscious that she was dragged in the wake of her mighty allies without regard to her special interests. Opposed to the Triple Alliance stood the Dual Alliance of Russia and France.

Alone of the great European powers, Britain did her best to keep free from the rival leagues' trammels. Even after necessity had forced her to show strong sympathy for the Dual Alliance, she hoped still to live on friendly terms with Germany and made no attempt to rival the armaments of the continental powers.

Her politicians turned a deaf ear to the veteran Lord Roberts's warnings that only general national service could prepare her for a great war. Haldane, who, as war minister, had done more than any other man for army reform, declared that enough had been accomplished to meet any eventuality.

Thus Britain blinded herself to the increasing arrogance of German claims. If war was avoided for so long, it was mainly because Germany was well content with the success of her policy of " peaceful penetration," supplemented upon occasion by threats, which generally resulted in her obtaining what she wanted.

Continental Troubles 1911-1913

Between 1911 and 1913, three new troubles showed that armed peace would not last much longer. The first of these was in Morocco, where there was war between the French and the disorderly government of that kingdom.

In 1911, the German Emperor sent the gunboat Panther to the port of Agadir, thus revealing his desire to interfere between France and Morocco.

The Anglo-French agreement had laid down that Morocco was within the French sphere of influence; Britain declared that she was prepared to support France against German attack.

The Kaiser withdrew the Panther and accepted a treaty that left France undisturbed in Morocco. It was a great triumph for the entente cordiale, but it left bad blood behind it.

Map of the European Countries Engaged in the Great War. Advanced History of Great Britain To 1918, 1920. GGA Image ID # 180338547a

The Turkish Revolution 1909

A second trouble was even more disturbing to Germany because it foreshadowed the Triple Alliance's breakdown by Italy's secession and opened up once more the eternal Eastern question, which had been comparatively quiet since the powers had put an end to the Greece-Turkish War of 1897.

There had been many disputes among the Christian states, between which the greater part of the Balkan peninsula had been divided since 1878. These became more dangerous since Turkey went through a domestic revolution in 1909.

By this, the Sultan, who had so cruelly oppressed the Armenians, was overthrown, and a new government set up, controlled by the Young Turks, who boasted that they would revive the Turkish power by introducing western methods of democracy and liberty.

They sought and obtained support in Germany and prepared to reorganize the Turkish army under German advisers. But the Christian subjects of Turkey, finding the Young Turks' rule as oppressive as that of the old Sultans, rose up in revolt, especially in Macedonia.

The Christian rebels included Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgars, but their jealousies of each other prevented the kingdoms of Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria from rendering effective aid to them.

For a time, the Macedonian troubles were thrown into the war's background, which broke out between 1911 and 1912 between Italy and Turkey.

To the disgust of Germany and Austria, Italy imposed a peace upon the Turks by which Tripoli and many islands in the Eastern Ægean remained in her hands.

The Balkan League 1912 and its Dissolution 1913

Worse for Germany was now to come, for the conclusion of the peace between Italy and Turkey was followed by the serious renewal of the Balkan troubles.

The easy defeat of the Turks encouraged the Balkan peoples to make up their feuds, and in 1912 all, except Romania joined in the Balkan League, concluded through the wise statesmanship of the Greek Prime Minister, Venizelos.

In 1912 the league took up arms against the Turks and drove them out of Macedonia. Behind the Balkan League was the unconcealed support of Russia and the sympathy of the Western powers.

But its success imperiled Germany's schemes of using her Turkish tools to establish her influence in Western Asia and threaten the British power in Egypt and India.

The league even more directly attacked Austria because Serbia's expansion blocked her path to Salonica and exposed her to Serbia's danger becoming the champion of the Southern Slavs of Croatia and Bosnia.

With the help of German princes, who reigned over most of the Balkan States, Germany and Austria broke up the Balkan League. Their task was easier since Greece and Serbia were quarreling with Bulgaria over the Turkish spoils' division.

Bulgaria now went to war against her rivals, whereupon Turkey resumed hostilities against her. But Romania, hitherto neutral, joined in Bulgaria's attack, which was soon forced to disgorge many of her conquests. The intervention of the powers forced an unsatisfactory peace on the Balkans in September 1913.

By it, Turkey in Europe was reduced to the districts between Adrianople and Constantinople, and the Balkan States, to which Albania was added, received large territory accessions.

But Austria annexed Bosnia and stopped Serbia from access to the sea. Moreover, Bulgaria secretly joined hands with the Central Powers. Like Turkey, they courted their support to re-establish her position at the Serbs' expense.

The Crime of Sarajevo and Its Consequences, June-August 1914

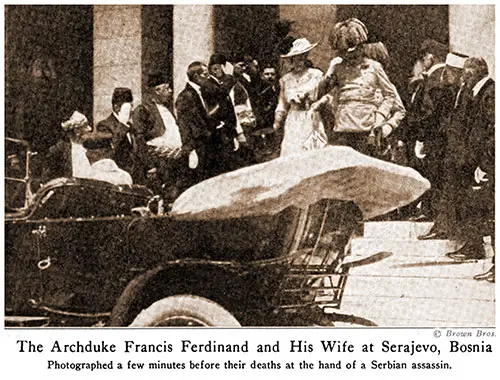

Archduke Francis Ferdinand and His Wife at Sarajevo, Bosnia. Photographed a Few Minutes before Their Deaths at the Hand of a Serbian Assassin. Photograph © Brown Bros. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 1: The Great Explosion, 1920. GGA Image ID # 197ef1e394

A great change now took place in German policy. There had long been an active German war party, but hitherto it had been kept in some check by the Emperor. But the threatened withdrawal of Italy from his alliance and the Central Powers' inability to stop the increase of Serbian territories convinced him that the time has come when Germany must fight.

If this was to be done, the sooner the war began, the better since Germany was ready, and her rivals, despite their elaborate preparations, were neither willing nor able to bring their forces rapidly into the field.

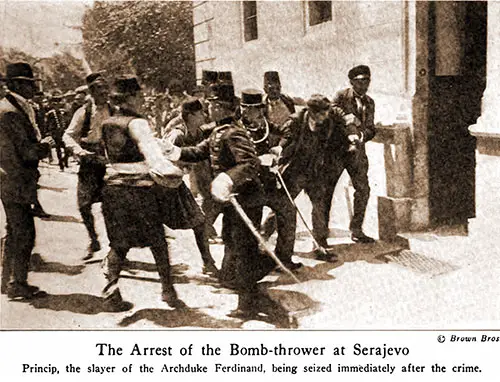

The arrest of the Bomb Thrower at Sarajevo. Princip, the Slayer of Archduke Ferdinand, Being Seized Immediately after the Crime. Photograph © Brown Bros. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 1: The Great Explosion, 1920. GGA Image ID # 197f4d7f95

An accidental calamity soon gave the pretext to fire the train, which set the world ablaze. In June 1914, as the archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne was driving through the streets of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, a Serb fanatic assassinated him.

Austria accused Serbia of complicity in the crime and demanded her unconditional submission. Serbia yielded nearly all that was asked, but in her terror appealed to Russia, Slavonic peoples' natural protector in distress.

Russia answered by setting her army on a war footing, whereupon Austria began hostilities against Serbia. Germany, who knew and approved Austria's action, ordered Russia to demobilize under the threat of immediate war.

On Russia's refusal, Germany and Austria declared war against her. Thereupon France, as bound by treaty, took up arms in defense of her eastern ally. Thus a general European war became inevitable.

T. F. Tout, M.A. F.B.A., "Origin of the Great War," in An Advanced History of Great Britain from the Earliest times to 1918, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1920.