The Loss of The Lusitania - 1920

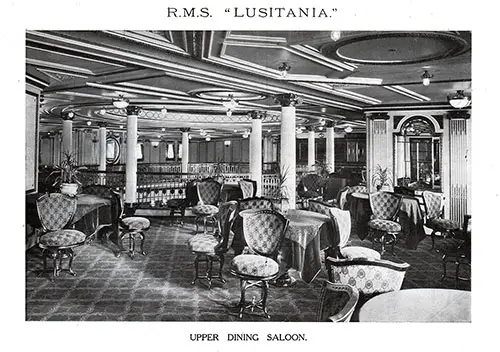

Upper Dining Saloon on the RMS Lusitania of the Cunard Line. Cunard Daily Bulletin, Campania Edition, 24 January 1908. GGA Image ID # 1980752734

The Official Report of the Inquiry into the Destruction of the Cunarder by a German Submarine

Lord Mersey's Report of The Sinking

The story of the Lusitania's loss is best told in the official report of Lord Mersey, the Wreck Commissioner of Great Britain:

Official Report on The Loss of The Lusitania (7 May 1915)

The Court, having inquired carefully into the circumstances of the disaster as mentioned above, finds, for the reasons appearing in the annex hereto, that the loss of the said ship and lives was due to damage caused to the said ship by torpedoes fired by a submarine of German nationality whereby the vessel sank. In the Court's opinion, the Germans did the act not merely to sink the ship but also to destroy the people's lives on board.

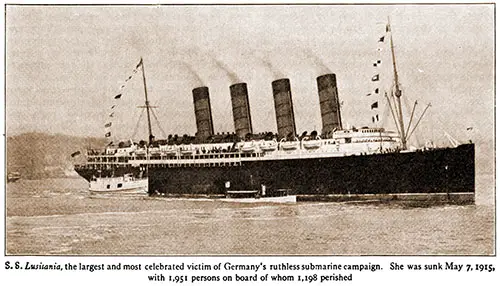

The Ship

SS Lusitania, the Largest and Most Celebrated Victim of Germany's Ruthless Submarine Campaign. She Was Sunk 7 May 1915 with 1,951 Persons on Board of Whom 1,198 Perished. The US in the Great War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 198048ff59

The Lusitania was a turbine steamship, built by John Brown & Co., of Clydebank, in 1907, for the Cunard Steamship Company. She was built under the Admiralty survey and following Admiralty requirements and was classed to A I at Lloyd's. Her length was 755 feet, her beam 88 feet, and her depth 60 feet 4 inches. Her tonnage was 30,395 gross and 12,611 net. Her engines were 68,000 h.p. and her speed 24 1/2 to 25 knots. She had 23 double-ended and two single-ended boilers situated in four boiler rooms.

The Captain, The Officers, And the Crew

The ship captain, Mr. William Thomas Turner, had been in the Cunard Company's service since 1883. He had occupied the position of commander since 1903 and had held an extra master's certificate since 1907. He was called before me and gave his evidence truthfully and well. The Lusitania carried an additional captain named Anderson...

The two captains and the officers were competent men, and ... they did their duty. Captain Turner remained on the bridge till he was swept into the sea. Captain Anderson was working on the deck until he went overboard and was drowned. Mr. Arthur Jones, the first officer, described the crew on this voyage as well able to handle the boats and testified to their carrying out the orders capably given to them.

One of the crew, Leslie N. Morton, who, when the ship was torpedoed, was an extra lookout on the starboard side of the forecastle head, deserves a particular word of commendation . . ..

He and Parry rowed the lifeboat some miles to a fishing smack, and, having put the rescued passengers on board the smack, they reentered the lifeboat and succeeded in rescuing twenty or thirty more people. With his mate, Parry, this boy was instrumental in saving nearly one hundred lives ...

No doubt there were mishaps in handling the boats' ropes and other such matters. Still, there was, in my opinion, no incompetence or neglect, and I am satisfied that the crew behaved well throughout and worked with skill and judgment. Many more than half their number lost their lives.

The entire crew consisted of 702. Of the males, 397 were lost, and of the females, sixteen, making the total number lost 413. The total number saved 289. I find that the conduct of the masters, the officers, and the crew was satisfactory. They did their best in complex and hazardous circumstances, and their best was good.

The Passengers

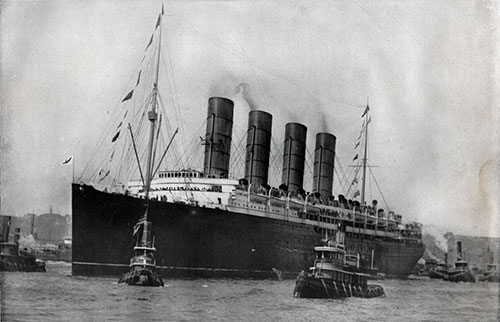

The RMS Lusitania of the Cunard Line Leaving Her Pier in New York. GGA Image ID # 19804653b2

The number of passengers on board the Lusitania when she sailed was 1,257, consisting of 290 saloon, 600 second-cabin, and 367 third -cabin passengers. Of these, 944 were British and Canadian, 159 were American, and the remainder were seventeen other nationalities.

Of the British and Canadian, 584 perished. Of the Americans, 124 perished, and of the rest, 77 perished. The total number was 785, and the total number saved was 472. The 1,257 passengers were 688 adult males, 440 adult females, 51 male children, 39 female children, and 39 infants.

Of the 688 adult males, 421 were lost and 267 saved. Of the 440 adult females, 270 were lost, and 170 were saved. Of the 51 male children, 33 were lost, and 18 were rescued. Of the 39 female children, 26 were lost, and 13 were saved. Of the 39 infants, 35 were lost, and four were saved.

Many of the women and children among those lost died from exhaustion after immersion in the water. I can speak very well of the conduct of the passengers after the striking of the ship.

There was little or no panic at first, although later on, when the steerage passengers came onto the boat deck in what one witness described as "a swarm," there appears to have been something approaching panic.

Some of the passengers attempted to assist in launching the boats and, in my opinion, did more harm than good. It is, however, quite impossible to attribute any blame to them. They were all working for the best.

View of the Upper and Lower First Class Dining Saloon and Dome on the RMS Lusitania. Travelling Palace, 1913. GGA Image ID # 1980898b9c

The Cargo

The cargo was a general cargo of the ordinary kind, but part consisted of several cases of cartridges (about 5,000). This ammunition was entered in the manifest. It was stowed well forward in the ship on the orlop and lower decks and about 50 yards away from where the torpedoes struck the ship. There was no other explosive on board.

The Ship Unarmed

It has been said by the German government that the Lusitania was equipped with masked guns, that she was supplied with trained gunners, with special ammunition, that she was transporting Canadian troops, and that she was violating the laws of the United States.

These statements are untrue: they are nothing but baseless inventions, and they serve only to condemn the persons who use them. The steamer carried no masked guns nor trained gunners or special ammunition, nor was she transporting troops or violating any United States laws.

The Torpedoing of The Ship

By 7 May, the Lusitania had entered the 'Danger Zone,' that is to say, she had reached the waters in which enemy submarines might be expected.

The captain had therefore taken precautions. He had ordered all the lifeboats under davits to be swung out. He had ordered all bulkhead doors to be closed except such as were required to be kept open to work the ship.

These orders had been carried out. The portholes were also closed. The ship's lookout was doubled—two men being sent to the crow's-nest and two men to the eyes of the ship. Two officers were on the bridge, and a quartermaster was on either side with instructions to look out for submarines.

Orders were also sent to the engine room between noon and 2 p.m. on the 7th to keep the steam pressure very high in case of emergency and give the vessel all possible speed if the bridge's telephone should ring.

At 2:15 p.m., when ten to fifteen miles off the Old Head of Kinsale. The weather is then clear and the sea smooth, the captain, who was on the lower bridge's port side, heard the call.

There is a torpedo coming, sir, given by the second officer. He looked to starboard and then saw a streak of foam in the wake of a torpedo traveling toward his ship.

Immediately afterward, the Lusitania was struck on the starboard side somewhere between the third and fourth funnels. The blow broke the number 5 lifeboat to splinters.

A second torpedo was fired immediately afterward, which also struck the ship on the starboard side. The two torpedoes struck the ship almost simultaneously.

Both these torpedoes were discharged by a German submarine from a distance variously estimated from two to five hundred yards. The Germans gave no warning of any kind.

It is also evidence that shortly afterward, the Germans fired a torpedo from another submarine on the port side of the Lusitania. This torpedo did not strike the ship; the circumstance is only mentioned to show that perhaps more than one submarine was taking part in the attack.

On being struck, The Lusitania took a heavy list to starboard, and in less than twenty minutes, she sank in deep water. Eleven hundred and ninety-eight men, women, and children were drowned.

Sir Edward Carson, when opening the case, described the course adopted by the German government in directing this attack as 'contrary to international law and the usages of war, and as constituting, according to the law of all civilized countries, a deliberate attempt to murder the passengers on board the ship.

This statement is, in my opinion, accurate, and it is made in a language, not a whit too strong for the occasion. The defenseless creatures on board, made up of harmless men and women and helpless children, were done to death by the German submarine crew acting under the directions of the officials of the German government.

In the questions submitted to me by the Board of Trade, I am asked, 'What was the cause of the loss of life? The answer is plain. The adequate cause of the loss of life was the attack made against the ship by those on board the submarine.

It was a murderous attack because made with a deliberate and wholly unjustifiable intention of killing the people on board. German authorities on the laws of war at sea themselves establish beyond all doubt that though the destruction of an enemy trader may be permissible in some cases, there is always an obligation first to secure the safety of the lives of those on board.

The guilt of the persons concerned in the present case is confirmed by the vain excuses put forward on their behalf by the German government as before mentioned...

It may be worthwhile noting that Leith, the Marconi operator, was also in the second-class dining saloon at the time of the explosion. He speaks of but one explosion. In my opinion, there was no explosion of any part of the cargo.

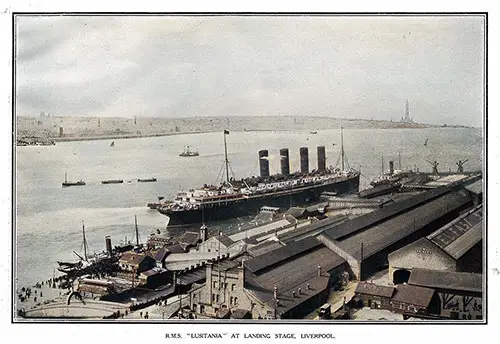

The RMS Lusitania at the Landing Stage at Liverpool, England. Cunard Daily Bulletin, Summer 1912 Edition. | GGA Image ID # 1980a5e1fb

Orders Given and Work Done After the Torpedoing

The captain was on the bridge when his ship was struck, and he remained there, giving orders until his vessel foundered. His first order was to lower all boats to the rail.

This order was obeyed as far as it possibly could be. He then called out, 'Women and children first." The order was then given to hard-a-starboard the helm to head toward the land, and orders were telegraphed to the engine room.

The orders delivered to the engine room are complicated. The crew obeyed this orders, apparent confusion about them. However, it is not essential to consider them, for the engines were put out of commission almost at once by the inrush of water and ceased working, and the lights in the engine room were blown out.

Leith, the Marconi operator, immediately sent out an S. O. S. signal and, later on, another message, 'Come at once, huge list, 10 miles south Head Old Kinsale.

These messages were repeated continuously and were acknowledged. At first, the messages were sent out by the power supplied from the ship's dynamo.

Still, in three or four minutes, this power gave out, and the messages were sent out employing the emergency apparatus in the wireless cabin.

All the collapsible boats were loosened from their lashings and freed so that they could float when the ship sank.

The Launching of The Lifeboats

Some made complaints of the witnesses about how the crew launched the boats and about their leaky condition when in the water. I do not question these witnesses' good faith, but I think their complaints were ill-founded...

The conclusion at which I arrive is that the boats were in good order at the moment of the explosion and that the launching was carried out and the short time, the moving ship, and the severe list would allow.

The Navigation of The Ship

At the request of the Attorney-General, part of the evidence in the inquiry was taken on camera. This course was adopted in the public interest.

The evidence in question dealt, firstly, with detailed advice given by the Admiralty to navigators generally regarding precautions to be taken to avoid submarine attacks; and secondly, with the information furnished by the Admiralty to Captain Turner individually of submarine dangers likely to be encountered by him in the voyage of the Lusitania.

It would defeat the object that the Attorney-General had in view if I were to discuss these matters in detail in my report; I do not propose doing so.

But it was made abundantly plain to me that the Admiralty had devoted the most anxious care and thought to the questions arising out of the submarine peril and that they had diligently collected all available information likely to affect the voyage of the Lusitania in this connection...

Indeed, Captain Turner did not follow the advice given to him in some respects. It may be (though I seriously doubt it) that had he done so, and his ship would have reached Liverpool in safety.

But the question remains, was his conduct the conduct of a negligent or of an incompetent man. On this question, I have sought my assessors' guidance, who has rendered me invaluable assistance, and the conclusion at which I have arrived is that blame ought not to be attributed to the captain.

Although meant for his most profound and careful consideration, the advice given to him was not intended to deprive him of the right to exercise his professional judgment in the difficult questions that might arise from time to time in the navigation of his ship. His omission to follow the advice made respect cannot reasonably be attributed either to negligence or incompetence.

He exercised his judgment for the best. It was the judgment of a skilled and experienced man, and although others might have acted differently and perhaps more successfully, he ought not, in my opinion, to be blamed.

The Whole Blame

The whole blame for the cruel destruction of life in this catastrophe must rest society with those who plotted and with those who committed the crime.

In the Metropolitan Magazine, August 1915, Colonel Roosevelt published Mrs. Wharton's translation of the following German poem, which illustrates how the Germans gloried in their wickedness:

The Hymn of the "Lusitania"

The swift sea sucks her death-shriek under

Aft the great ship reels and leaps asunder.

Crammed taffrail-high with her murderous freight,

Like a straw on the tide, she whirls to her fate.

"A warship she, though she lacked its coat,

And lustful for lives as none afloat,

A warship, and one of the foe's best workers,

Not penned with her rusting harbor-shirkers.

"Now the Flanders guns lack their daily bread,

And shipper and buyer are sick with dread,

For neutral as Uncle Sam may be,

Your surest neutral's the deep green sea.

"Just one ship sunk, with lives and shell,

And thousands of German gray coats well!

And of each of her gray coats, German hate.

Would have sunk ten ships with all their freight.

"Yea, ten such ships are a paltry fine.

For one good life in our fighting line.

Let England ponder the crimson text:

TORPEDO, STRIKE! AND HURRAH FOR THE NEXT!"

Based on the Article "The Loss of the Lusitania: The Official Report of the Inquiry into the Destruction of the Cunarder by a German Submarine," in Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume I: The Great Explosion -- Background and Origins of the World War, New York-London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1920, pp. 362-365