The Sinking of the Lusitania and WW1 - 1917

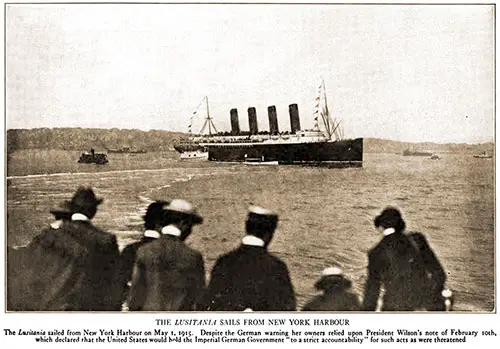

The Lusitania Sails from New York Harbor. The Lusitania Sailed from New York Harbor on 1 May 1915. Despite the German Warning, Her Owners Relied upon President Wilson's Note of 10 February 1915 Which Declared That the United States Would Hold the Imperial German Government "To a Strict Accountability" for Such Acts as Were Threatened. History of the World War, Vol. 4: America and Russia, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18a43c2647

The Lusitania was, in the eyes of the German Admiralty, the symbol of Great Britain's supremacy on the seas. The big, graceful vessel, unsurpassed in speed, had defied the German raiders that lurked in the Atlantic hoping to capture her and had eluded the sub marines that tried to find her course.

Time and time again, the Germans had planned and plotted to "get" the Lusitania and, every time, the ocean greyhound had slipped away from them every time save when the plot was developed on Ameri can territory.

To sink the Lusitania, the German admiralty had argued, was to lower England's prestige and to hoist the black eagle of the Hohenzollerns above the Union Jack. Her destruction, they fondly hoped, would strike terror to the hearts of the British; for it would prove the inability of the English navy to protect her merchantmen.

It would prove to the world that von Tirpitz was on a fair way of carrying out his threat to isolate the British Isles and starve the British people into submission to Germany. It would be a last warning to neutrals to keep off the Allies' merchant 163 men and would help stop the shipment of arms and ammunition to the Allies from America.

It would — as a certain royal personage boasted — shake the world's foundations.

Gloating over their project and forgetting the rights of neutrals, the mad war lords did not think of the innocent persons on board, the men, the women and babies. The lives of these neutrals were as nothing compared with the shouts of triumph that would resound through Germany at the announcement of the torpedoing of the big British ship, symbol of sea power.

GERMAN OFFICIAL REPORT

[By The Associated Press.]

BERLIN, May 14, (via Amsterdam to London, May 15.)—From the report received from the submarine which sank the Cunard Line steamer Lusitania last Friday the following official version of the incident is published by the Admiralty Staff over the signature of Admiral Behncke:

The submarine sighted the steamer, which showed no flag, May 7 at 2:20 o'clock, Central European time, afternoon, on the southeast coast of Ireland, in fine, clear weather.

At 3:10 o'clock one torpedo was fired at the Lusitania, which hit her starboard side below the Captain's bridge. The detonation of the torpedo was followed immediately by a further explosion of extremely strong effect. The ship quickly listed to starboard and began to sink.

The second explosion must be traced back to the ignition of quantities of ammunition inside the ship.

It appears from this report that the submarine sighted the Lusitania at 1:20 o'clock, London time, and fired the torpedo at 2:10 o'clock, London time.

The Lusitania, according to all reports, was traveling at the rate of eighteen knots an hour, as fifty minutes elapsed between the sighting and the torpedoing, the Lusitania when first teen from the submarine must have been distant nearly fifteen knots, or about seventeen land miles.

The Lusitania must have been recognized at the first appearance of the tops of her funnels above the horizon. To the Captain on the bridge of the Lusitania the submarine would ha"c been at that time invisible, being below the horizon.

The attitude was truly expressed by Captain von Papen who on receiving news of the sinking of the Lusitania remarked: “Well, your General Sherman said it: 'War is Hell.' "

So the war lords schemed and the plots which resulted in the sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, bringing death to 113 American citizens, were developed and executed in America, through orders from Berlin.

The agents in America put their heads together in a room in the German Club, New York, or in a high-powered limousine tearing through the dark. These men, who had worked out the plot, on the night of the successful execution had assembled in a club and in high glee touched their glasses and shouted their devotion to the Kaiser.

One boasted afterward that he received an Iron Cross for his share in the work. On the night of the tragedy, one of the conspirators remarked to a family where he was dining - a family whose son was on the Lusitania - when word came of the many deaths on the ship: " I did not think she would sink so quickly. I had two good men on board.”

Warriors at Work in America

In their secret conferences the conspirators worked their way round obstacles and set their scheme in operation.

Hired spies had made numerous trips on the Lusitania and had carefully studied her course to and from England, and her convoy through the dangerous zone where submarines might be lurking. These spies had observed the precautions taken against a submarine attack. They knew the fearful speed by which the big ship had eluded pursuers in February.

They also had considered the feasibility of sending a wireless message to a friend in England a message apparently of greeting that might be picked up by the wireless on a German submarine and give its commander a hint as to the ship's course. In fact, they did attempt this plan.

Spies were on board early in the year when the Lusitania ran dangerously near a submarine, dodged a torpedo and then quickly eclipsed her German pursuer. Spies also had brought reports concerning persons connected with the Lusitania and had given suggestions as to how to place men on board in spite of the scrutiny of British agents.

All these reports were considered carefully, and the conclusion was that no submarine was fast enough to chase and get the Lusitania; that it was practically impossible to have the U-boats stationed along every half mile of the British coast, but that the simplest problem was to send the Lusitania on a course where the U-boats would be in waiting and could torpedo her.

The scheme was, in substance, as follows:

- “Captain Turner, approaching the English coast, sends a wireless to the British Admiralty asking for instructions as to his course and convoy. He gets a reply in code telling him in what direction to steer and where his convoy will meet him.

- First, we must get a copy of the Admiralty Code and we must prepare a message in cipher giving directions as to his course. This message will go to him by wireless as though from the Admiralty.

- We must make arrangements to see that the genuine message from the British Admiralty never reaches Captain Turner.”

That was the plan which the conspirators, aided and directed by Berlin, chose. Upon it, the shrewdest minds in the German secret service were set to work. As for the British Admiralty Code, the Germans had that at the outbreak of the war and were using it at advantageous moments.

How they got it, has not been made known; but they got it and they used it, just as the Germans have obtained copies of the codes 166 used by the American State Department and have had copies of the codes used in our Army and Navy.

While the codes used by the British officials change almost daily, such is not the case with merchant vessels on long voyages. The next step of the conspirators was to arrange for the substitution of the fake message for the genuine one.

Germany's spy machine has a wonderful faculty for seeking out the weak characters holding responsible positions among the enemy or for sending agents to get and hold positions among their foes. It is now charged that a man on the Lusitania was deceived or duped.

Whether he was a German sympathizer sent out by the Fatherland to get the position and be ready for the task, or whether he was induced for pay to play the part he did, has not been told . Neither is his fate known. Communication between New York and the German capital, ingenious, intricate and superbly arranged, was just as easy almost as telephoning from the Battery to Harlem.

Berlin was kept informed of every move in New York and in fact selected the ill-fated course for the Lusitania's last voyage in English waters. Berlin picked out the place where the Lusitania was to sink.

Berlin chose the deep, sea graves for more than 100 Americans. Berlin assigned two submarines to a point ten miles south by west off Old Head of Kinsale, near the entrance of St. George's Channel.

Berlin chose the commander of the U-boats for the most damnable sea-crime in history Just here, there is a rumor among U-boat men in Europe that the man for the crime was sent from Kiel with sealed instructions not to be opened till at the spot chosen. With him went "a shadow" charged with a death warrant if the U-boat commander "balked” at the last moment.

Berlin Gives Warning

The German officials in Berlin looking ahead —and the Kaiser's statement have a wonderful faculty of foresight— sought to prearrange a palliative for their crime. Their plan, which in itself shows clearly how carefully the Germans plotted the destruction of the Lusitania, was to warn Americans not to sail on the vessel.

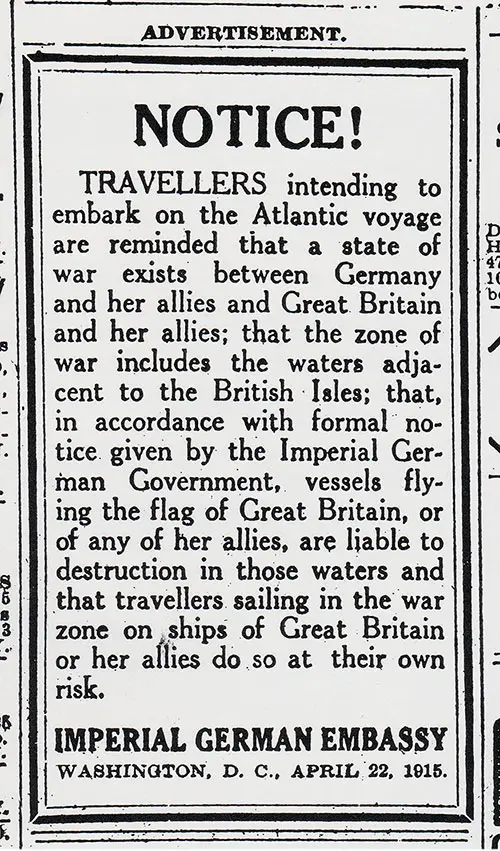

While the German Embassy in Washington was kept clear of the plot and Ambassador von Bernstorff had argued and fought with all his strength against the designs of the Berlin authorities, he, nevertheless, received orders to publish an advertisement warning neutrals not to sail on the Allies' merchantmen.

Acting under instructions, this advertisement was inserted in newspapers in a column adjoining the Cunard's advertisement of the sailing of the Lusitania:

NOTICE — Travelers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her Allies and Great Britain and her Allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her Allies are liable to destruction in these waters and that travelers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her Allies do so at their own risk. Signed: Imperial German Embassy Washington , D. C., April 22, 1915. | GGA Image ID # 1976d3069d

Germans in New York, who had knowledge that German submarines were lying in wait off the Irish coast to "get" the Lusitania sent intimations to friends before the sailing of the ship.

The “New York Sun” was told of the plot and warned Captain Turner by wireless after the ship sailed. The German secret service in New York also sent warnings to Americans booked on the Lusitania.

One of the persons to receive such a message signed “morte” was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt. Many other passengers got the same warning that the ship was to be torpedoed; but they all laughed at it. They knew she had outrun submarines on a previous voyage and tricked them on another voyage.

Besides, before the horrors of this war, optimistic Americans firmly believed the world was a civilized place. It was only after the destruction of the Lusitania that many neutral Americans could credit the atrocity stories of Belgium

Fateful 1 May 1915

So when the Lusitania backed from her pier in the North River on the morning of May 1, 1915, there was more than the average levity that makes the sailing of an ocean liner so absorbing.

On the pier were anxious friends somewhat perturbed by the mysterious whisperings of impending danger. Mingling among them also were men who knew what that danger was, and who had just delivered final instructions to German hirelings on board.

On the deck of the great vessel, as she swung her nose down-stream toward Sandy Hook, was not only the man who had promised to see that the false message in code reached Captain Turner, but there also were those two friends, good and true, of von Rintelen's — men who, in the event that the Lusitania should run into the appointed place at night, would flash lights from port holes to give a clear aim to the captain of the stealthy submarines.

On board the vessel swinging out past Sandy Hook into the ocean lane were a notable group of passengers, many of them representative Americans of inestimable value to this country. Besides Mr. Vanderbilt, there was Charles Frohpart, a talented theatrical producer, who had furnished by his artistic shows genuine amusement to millions; Elbert Hubbard, talented and inspiring writer; Charles Klein, writer of absorbing plays; Justus Miles Forman , novelist, and Lindon W. Bates , Jr., whose family had befriended von Rintelen.

Merchants, clergymen, lawyers, society women, a large list of useful men and women in the 1,254 passengers. These, added to the crew of 800, made more than 2,000 lives under the care of the staunch, blue-eyed captain. Of that number, 1,214 were being rushed over the waves to doom. And as the ship sped eastward, submarines leaving their bases at Cuxhaven and Heligoland clipped their prows under the waves, and made for Old Head of Kinsale on the south coast of Ireland, where they were instructed to pause, upon sealed instructions and obey them to the letter.

Meantime, Berlin, counting almost to the hour when the Lusitania would near the British Isles, prepared the exact wording for the false instructions to Captain Turner. This was sent to New York by wireless, where it was put into British code.

The next step was to have this message substituted for the British Admiralty's instructions to the Lusitania. The inside details of how this substitution was effected can only be surmised. This secret is buried with the British Admiralty and with the Bureau in Berlin.

Berlin's Deliberations

For such intricate action Germany had been preparing with infinite patience both before and after the war began.

Prior to the outbreak, representatives of Germany had started the building of the wireless plant at Sayville, Long Island, by which aerial communication was established with Berlin.

After the war began, the equipment of the station was increased, and instead of 85 kilowatt transmitters, 100 kilowatt transmitters were installed, the machinery for tripling the efficiency of the plant having been shipped from Germany via Holland to this country.

Wireless experts, members of the German navy, also slipped away from Germany to direct the work of handling messages between the two countries. Everything was in readiness at Sayville, consequently, to catch the directions that were flashed through the air.

There was an operator specially trained to take the message coded for the deception of Captain Turner, and send it crackling fatefully through the air. Everything was ready and only the request of the operator on the Lusitania for directions south of Ireland was needed.

All this was in violation not only of our neutrality laws, but also in disregard of American statutes governing wireless stations. Meantime, the vessel had reached the edge of the war zone decreed by Germany in violation of international law, and Captain Turner sent out his call for instructions.

Presently the order came. It was hurried to Captain Turner's stateroom. Captain Turner, carefully decoding the message by means of a cipher book which he had guarded so jealously, read orders to proceed to a point ten miles south of Old Head of Kinsale, and run into St. George's Channel, making the bar at Liverpool at midnight.

He carefully calculated the distance and his running time, and adjusted his speed accordingly. He felt assured, because he relied on the assumption that the waters over which he was sailing were being thoroughly scoured by English cruisers and swift torpedo boats in search of German submarines.

The Explosion That Rocked the World

The British Admiralty also received his wireless message -- just as the Sayville operator had snatched it from the air, and dispatched an answer. The order from the head of the Admiralty directed the English captain to proceed to a point some 70 or 80 miles south of Old Head of Kinsale and there meet his convoy, which would guard him on the way to port.

But Captain Turner never got that message, and the British convoy waited in vain for the Lusitania to appear on the horizon.

The Lusitania headed northeast, going far away from the vessels that would have protected her. Swiftly she slipped through the waves on the afternoon of May 7.

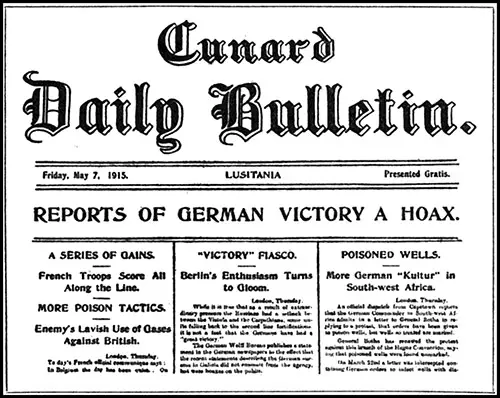

Lusitania's Last Cunard Daily Bulletin, Lusitania Edition, from Friday, 7 May 1915. GGA Image ID # 1d4bee9105

Unsuspecting, the ship moved directly toward certain death. The proud, swift liner steered straight between two submarines, lying in wait.

As Captain Tuner heard the explosion of the torpedo he instantly knew that there had been treachery. He knew he had been decoyed away from the warships that were to escort him to his pier. The manner in which the captain had been lured to the waiting submarines was made clear at the secret session of the Board of Inquiry that investigated the sinking of the ship.

Captain Turner told at the Corner's inquest how he had been warned, supposedly by the British Admiralty, of submarines off the Irish coast, and that he had received special instructions as to course. Asked if he made application for a convoy, he said: “No, I left that to them. It is their business, not mine. I simply had to carry out my orders to go , and I would do it again.”

At the official inquiry, the captain produced the orders which he had received, directing him to proceed southwest of Old Head of Kinsale. The British Admiralty produced its message which had directed Captain Turner to go by an utterly different course. It produced also orders which had been issued to the convoy to meet the Lusitania . The orders did not jibe. They showed treachery , and further investigation pointed to Sayville.

America Revolted and Appalled

The indignation and the revulsion of Americans against Germany because of the destruction of the Lusitania with the appalling loss of life was a surprise to the Kaiser and his war staff.

They apparently had believed that the warning contained in the official announcement of Ger many, declaring the waters about the British Islands a war zone, and the advertisement published would be sufficient excuse, and that their act would be accepted calmly by America.

They were not prepared for Colonel Roosevelt's invective stigmatizing the act as piracy or the editorial denunciation throughout the country. Their effrontery was displayed by one of their agents, who announced that American ships also would be sunk.

But this agent's removal from the country and mob violence threatened other agents was emphatic proof of America's state of mind.

Immediately Germany turned as a defense to the argument that the Lusitania carried munitions of war and other contraband in violation of the United States Federal statute. But the American laws were quoted to Ambassador von Bernstoff to prove to him that cartridges could be transported in a passenger ship. That argument proved of no avail.

Secretary Bryan's note, written by President Wilson , and forwarded to Berlin, demanded a disavowal of the sinking of the Lusitania , an apology and reparation for the lives lost. But Germany sought to parley with a reply that would lay the blame on Great Britain, charging that the Lusitania had been an armed auxiliary cruiser, requested an investigation of these alleged facts, and refused to stop her submarine warfare until England changed her trade policy. But this note again aroused the wrath of Americans.

Lies and Deceit

German secret agents began to manufacture evidence to support the Kaiser's contentions. Here a hireling of Boy-Ed looms as an obedient servant of the naval attaché, whether he knew all the facts or not. It was Koenig, who, using the alias of Stemler, obtained from Gustave Stahl an affidavit to the effect that he had seen four fifteen centimeter guns on the decks of the Lusitania before she left port on her ill-fated voyage.

There were three other supporting affidavits. All these documents were handed to Boy-Ed on June 1, 1915, and the following day were in the hands of von Bernstorff, who turned them over to the State Department in Washington.

It required but little work on the part of Federal agents to establish the untruth of Stahl's affidavit. Stahl, a German reservist, appeared before the Federal Grand Jury where he again repeated his lies. He was indicted for perjury and upon a plea of guilty was sent to the Federal prison at Atlanta.

It was Koenig who had hidden Stahl away after the latter had made his affidavit, and it was Koenig who, at the command of the Federal authorities, produced him . So here again Germany's efforts to deceive and to palliate her piratical act came to naught, and left her even more damned before the world.

Time came within a few days for President Wilson to reject forcibly the flimsy defense made by Germany, but before that note was drafted, the United States authorities by a thorough investigation of Sayville, and a scrutiny of the German naval officers employed there, discovered that the fake code message that drove the Lusitania to her grave in the sea had been flashed out from neutral territory; that the conspiracy had been developed in America, though the details were not obtainable at that time as they are presented here.

President Wilson was determined to demand the absolute safety for Americans at sea. Though Bryan resigned, Mr. Wilson sent a note, asserting that the Lusitania was not armed, and had not carried cargo in violation either of American or international law.

The action of Bryan weakened the position of America in demanding a cessation of Germany's submarine warfare. It gave encouragement to Austria, after Germany had promised to obey international law, to try a series of similar evasions.

It gave impetus to Germany's plans to make a settlement of the submarine controversy and to try to divide Congress on the issue. The loss to America was 113 lives and a great amount of prestige; to Germany, a tremendous amount of sympathy.

But through it all, stand out the pictures of secret agents, boasters , schemers and reckless adventurers, one of whom, having aided in the sinking of the Lusitania and the drowning of hundreds of her passengers and crew, had still the audacity to dine on the evening of this ghastly triumph at the home of an American victim.

One agent high in international affairs, overcome by the force of the tragedy done in answer to the Kaiser's bidding, had still enough decency left to remark: “Oh, what foul work !"

GERMAN NOTE OF REGRET

BERLIN, (via London.) May 10.—The following dispatch has been sent by the (Sermon Foreign Office to the German Embassy at Washington:

Please communicate the following to the State Department: The German Government desires to express its deepest sympathy at the loss of lives on board the Lusitania. The responsibility rests, however, with the British Government, which, through its plan of starving the civilian population of Germany, has forced Germany to resort to retaliatory measures.

In spite of the German offer to stop the submarine war in case the starvation plan was given up, British merchant vessels are being generally armed with guns and have repeatedly tried to ram submarines, so that a previous search was impossible.

They cannot, therefore, be treated as ordinary merchant vessels. A recent declaration made to the British Parliament by the Parliamentary Secretary in answer to a question by Lord Charles Berc8ford said that at the present practically ail British merchant vessels were armed and provided with hand grenades.

Besides, it has been openly admitted by the English press that the Lusitania on previous voyages repeatedly carried large quantities of war material. On the present voyage the Lusitania carried 5,400 cases of ammunition, while the rest of her cargo also consisted chiefly of contraband.

If England, after repeated official and unofficial warnings, considered herself able to declare that that boat ran no risk and thus light-heartedly assumed responsibility for the human life on board a steamer which, owing to its armament and cargo, was liable to destruction, the German Government, in spite of its heartfelt sympathy for the loss of American lives, cannot but regret that Americans felt more inclined to trust to English promises rather than to pay attention to the warnings from the German side. FOREIGN OFFICE.

ENGLAND ANSWERS GERMANY

[By The Associated Press]

LONDON, Wednesday, May 12.—Inquiry in official circles elicited last night the following statement, representing the official British view of Germany's justification for torpedoing the Lusitania which Berlin transmitted to the State Department at Washington:

The German Government states that responsibility for the loss of the Lusitania rests with the British Government, which through their plan of starving the civil population of Germany has forced Germany to resort to retaliatory measures. The reply to this is as follows:

As far back as last December Admiral von Tirpitz, (the German Marine Minister,) in an interview, foreshadowed a submarine blockade of Great Britain, and a merchant ship and a hospital ship were torpedoed Jan. 30 and Feb. 1, respectively.

The German Government on Feb. 4 declared their intention of instituting a general submarine blockade of Great Britain and Ireland, with the avowed purpose of cutting off supplies for these islands. This blockade was put into effect Feb 18.

As already stated, merchant vessels had, as a matter of fact, been sunk by a German submarine at the end of January. Before Feb. 4 no vessel carrying food supplies for Germany had been held up by his Majesty's Government, except on the ground that there was reason to believe the foodstuffs were intended for use of the armed forces of the enemy or the enemy Government.

His Majesty's Government had, however, informed the State Department on Jan. 29 that they felt bound to place in a prize court the foodstuffs of the steamer Wilhelmina, which was going to a German port, in view of the Government control of foodstuffs in Germany, as being destined for the enemy Government, and, therefore, liable to capture.

The decision of his Majesty's Government to carry out the measures laid down by the Order in Council was due to the action of the German Government in insisting: on their submarine blockade.

This, added to other infractions of international law by Germany, led to British reprisals, which differ from the German action in that his Majesty's Government scrupulously respect the lives of noncombatants traveling in merchant vessels, and do not even enforce the recognized penalty of confiscation for a breach of the blockade, whereas the German policy is to sink enemy or neutral vessels at sight, with total disregard for the lives of noncombatants and the property of neutrals.

The Germans state that, in spite of their offer to stop their submarine war in case the starvation plan was given up, Great Britain has taken even more stringent blockade measures. The answer to this is as follows:

It was not understood from the reply of the German Government that they were prepared to abandon the principle of sinking British vessels by submarine.

They have refused to abandon the use of mines for offensive purposes on the high seas on any condition. They have committed various other infractions of international law, such as strewing the high seas and trade routes with mines, and British and neutral vessels will continue to run danger from this course, whether Germany abandons her submarine blockade or not.

It should be noted that since the employment of submarines, contrary to international law, the Germans also have been guilty of the use of asphyxiating gas. They have even proceeded to the poisoning of water in South Africa.

The Germans represent British merchant vessels generally as armed with guns and say that they repeatedly ram submarines. The answer to this is as follows:

It is not to be wondered at that merchant vessels, knowing they are liable to be sunk without warning and without any chance being given those on board to save their lives, should take measures for self-defense.

With regard to the Lusitania: The vessel was not armed on her last voyage, and had not been armed during the whole war.

The Germans attempt to justify the sinking of the Lusitania by the fact that she had arms and ammunition on board. The presence of contraband on board a neutral vessel does render her liable to capture, but certainly not to destruction, with the loss of a large portion of her crew and passengers. Every enemy vessel is a fair prize, but there is no legal provision, not to speak of the principles of humanity, which would justify what can only be described as murder because a vessel carries contraband.

The Germans maintain that after repeated official and unofficial warnings his Majesty's Government were responsible for the loss of life, as they considered themselves able to declare that the boat ran no risk, and thus "light- heartedly assume the responsibility for the human lives on board a steamer which, owing to its armament and cargo, is liable to destruction." The reply thereto is:

First — His Majesty's Government never declared the boat ran no risk.

Second—The fact that the Germans issued their warning shows that the crime was premeditated. They had no more right to murder passengers after warning them than before.

Third—In spite of their attempts to put the blame on Great Britain, it will tax the ingenuity even of the Germans to explain away the fact that it was a German torpedo, fired by a German sea. man from a German submarine, that sank the vessel and caused over 1,000 deaths.

John Price Jones, "The Story of the Lusitania" in America Entangled, New York: The William G. Hewitt Press, 1917, pp. 161-

The Associated Press, "The Warning and The Consequence--German Official Report," in The New York Times Current History: The European War, June 1915, Vol. II, No. 3, pp. 413-414.

German Foreign Office, "The Warning and The Consequence--German Note of Regret," in The New York Times Current History: The European War, June 1915, Vol. II, No. 3, p. 415.

The Associated Press, "The Warning and The Consequence--England Answers Germany," in The New York Times Current History: The European War, June 1915, pp. Vol. II, No. 3, 415-416.