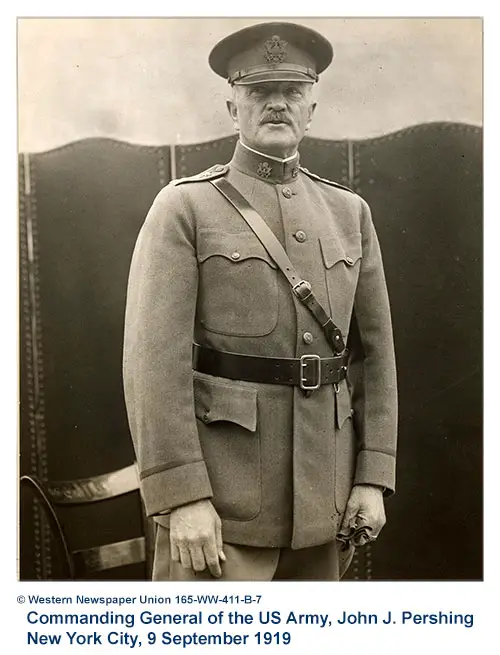

John J. Pershing Commander of The Army of The United States

Commanding General of the US Army, John J. Pershing at New York City, 9 September 1919. Photograph by Western Newspaper Union. National Archives & Records Administration No. 45528933. Local ID: 165-WW-411-B-7. GGA Image ID # 186b7a5cd7

WHEN the United States entered the great world war it did so from purely chivalrous motives. England and France had borne the brunt of furious fighting for four years and their armies had lost their snap, or “ pep.” As a matter of fact, upon the western front the situation was about that which one calls “stalemate” in chess: neither side, Germans or Allies, could move either way. They were locked in each other’s embraces in a deathly, vice-like grip.

It was for the soldiers of the United States to turn the balance in favor of the Allies, and this they were intent upon because it became evident to all that it required more men than either France or England could muster to make a “ clean up ” and to push the German hordes back upon their own soil.

The United States army was, therefore, utilized as a third team, put into the scrimmage when the game between the other two teams was about over. Fresh men can always beat an exhausted eleven, and so the United States Army, full of élan, well equipped, eager to do or to die, turned the balance in favor of the Allies and helped very materially to win the day.

To command the American troops was selected General John Joseph Pershing, familiarly known as “Blackjack," who was the son of a section foreman on one of the western roads. His only advantageous heritage was that of a sound and healthy body. Handicapped by poverty and lack of early opportunity, he created a career by sheer force of personality and will power.

When a small boy the General determined that he wanted to lead the life of a soldier and he hoped to attain this ambition. Born in the Middle West, at La Clede, Missouri, quite naturally his schooling there was simple and rudimentary, as the facilities for education were meager, and he began to think that he could never be a lighting man.

Young Pershing, however, learned enough to secure his admission to the Normal School at Kirksville, where, in order to support himself, he taught a class of negroes. He instructed these young charges with all the pains and the patience that he was to use later in the instruction of the cadets at West Point.

Just at this time the Attorneys were having a great deal of business in the Middle West, so the youthful teacher decided that he wanted to follow in the steps of Abraham Lincoln and become a member of the learned profession of the law.

But there was an opportunity offered for attaining a cadetship at West Point, and, after taking the competitive examination, young Pershing found himself chosen to learn the profession to which he had always aspired — when not contemplating a legal career. The Missouri teacher and son of a section-hand boss now found himself a plebe at West Point.

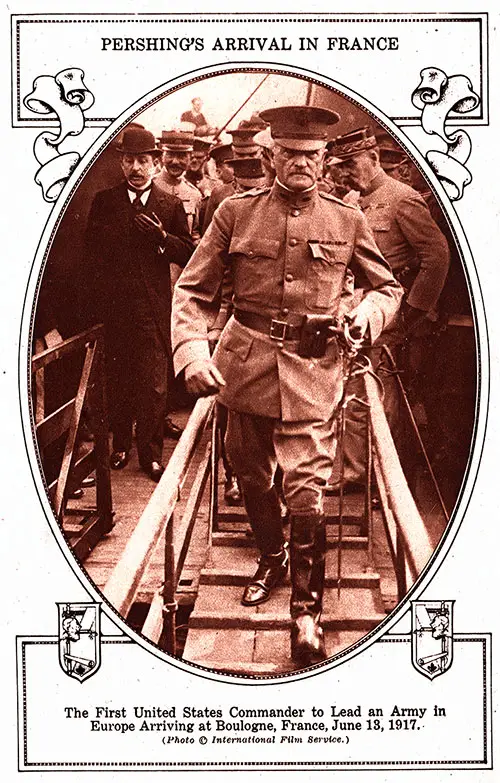

General John Pershing's Arrival in France. The First United States Commander to Lead an Army in Europe Arriving at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, 13 June 1917. Photograph © International Film Service. Current History Magazine, August 1917. GGA Image ID # 18def12deb

In the bracing air of the Hudson River, the energetic Pershing learned how to be a soldier and how to do “squads right.” He also learned that physical fitness was an excellent thing to have, so that in after years the now famous General has always taken particular pains to keep himself in good condition. He has been a great horse-back rider, a good fencer, and keen shot and sportsman. He first was taught how to lead the athletic life at Uncle Sam’s great military preparatory school.

Graduating in 1886, our newly fledged Lieutenant Pershing was sent out West where the wild Geronimo, the bloodthirsty Apache Chief, was murdering the peaceful settlers of Arizona and New Mexico. This arrogant savage was followed across the Mexican border and was chased for miles, until he was finally surrounded and captured in the mountains. It was the same ground over which Francisco Villa was to operate, with his Mexican bandits, against the United States in 1916.

In this campaign the young and ardent lieutenant received his first distinction. He was highly complimented by General Miles for marching his troop, with its pack train, one hundred and forty-six miles in forty- six hours, and for bringing in every man and every pack animal in good condition. The same interest which he then displayed for the welfare of his men he now displays for the welfare of the great army under his command.

Young Pershing was kept out on the plains and had a great deal of experience with the redskins, both peaceful and war-like. In 1896, the Zuni Indians became obstreperous and had considerable trouble with the set- tiers in the neighborhood of their reservation. Pershing happened to be near at the time, and when he learned that some cowboys had been imprisoned by the redskins, he hastened to their rescue.

The Zunis had decided to torture their prisoners and to have a good time while they were doing it, but Lieutenant Pershing had arrived just in time. The cowboys were rescued before the Indians had an opportunity to vent their wrath upon the poor fellows.

This incident was brought to the attention of the Lieutenant's superior officer, General Carr, who immediately recommended him to the Secretary of War, as an officer “high in his discretionary powers.” Yet the ambitious soldier was not jumped forward to a Captaincy at this time. He had to win his way by slow and gradual stages, and by still harder work.

The life of the now prominent General was practically without incident until the time of the Spanish war in 1898. At this time he was Captain of the 9th Cavalry and was sent immediately to Cuba in order to engage in the Santiago campaign, he was at the battles of San Juan and of Santiago, where he showed such bravery under fire that he was recommended for the brevet-commission of Colonel "for personal gallantry, untiring energy, and faithfulness."

Returning to the United States shortly after the surrender of the Spaniards, he was immediately dispatched to the Philippine Islands in order to subdue the war-like and vindictive Moros, a tribe which the Spaniards had not conquered in three hundred years.

That Pershing conducted himself well is known to all. The Moro was beaten into taking up “the white man’s burden,” and yet when subjugated they were treated with such kindness and fairness by the great white chieftain that he was made an hereditary ruler with royal rank and power of life and death over the natives.

General Pershing on His Way to Hotel de Ville on the French Independence Day, 14 July 1918. Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18deff3e00

This title was bestowed upon him by the Sultan of Oato, who also presented him with his son, a boy eighteen years of age. But the United States Government made him Governor of the Islands, and we now find him busied in attempting to conciliate these people whom Spain could never control.

The Moros were treated with tact, firmness, and fairness. In spite of all of his kindness, Captain Pershing would wage unrelenting warfare against the islanders whenever they rebelled. His soldiers would chase them through jungles and fever-stricken swamps and would allow them no rest, whenever their hearts turned bad against the whites.

Yet, when they were made to behave, no one treated them with more gentleness or consideration than did the future leader of the American army in France. Governor Pershing learned the native language and also the traditions and customs of this island people. He heard their grievances, their needs, and their various troubles. In time the Moros appreciated that here was not an enemy but a friend, and they changed their vindictive hatred of the white invader to friendliness.

The Governor of these fierce tribesmen conducted himself in such an able fashion that his merit was recognized by President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1903 Congress was asked to enact legislation which would allow a promotion of Captain Pershing to a higher rank, without jumping him to the position of Brigadier General. But Congress would not and did not act, so the energetic Roosevelt jumped the Governor to the Moros over the heads of eight hundred and sixty-two officers of grades senior to his, which was the longest jump in the history of army promotions.

Because of his excellent conduct in the Moro campaign, the hard-working soldier had thus received unsolicited promotion, but in addition to this he bears the unique distinction of being the only army officer complimented by name in the President’s message to Congress. Of course this compliment had paid him because of his excellent conduct of the Moro campaign.

But other compliments had handed him, for, when war broke out between Russia and Japan, he was selected as the military observer for the United States, and still later, when chaos reigned in Mexico, Pershing was asked to control the vast United States army collected upon the border, and later was ordered to head a punitive expedition which penetrated Mexican territory.

The expedition was successful in that it had the desired effect: it put a stop to disorder in Northern Mexico, and although living in an unfertile and arid land, the General succeeded in bringing out his army with but few deaths from disease and the missiles of snipers.

Although seldom heard of before, the name of Pershing was now upon every tongue, and he was one of the best-known soldiers in the United States. The newspapers rang with the name of the leader of the Mexican Expedition. The moving pictures showed numerous scenes in Mexico and on the border, in which the erect, gray-haired general was to the front, and the paragraph writers spoke now of Pershing and not of Funston, the capturer of Aguinaldo, who had recently died of heart failure.

General Pershing at the Tomb of Lafayette. Photo by International Film Service. Though a man of few words, the American commander in France is a forceful speaker and evidently his sentiments have met with the approval of Marshal Joffre who stands directly in front of him and is applauding enthusiastically. Perhaps the occasion recalls to the Hero of the Marne the days of his own visit to America when he, and not the American general, laid wreaths on tombs and was the center of popular enthusiasm. This picture, however, is proof of the success of Joffre’s mission to America, for he came to ask that American troops be sent to France’s aid immediately, and here we see the United States commander-in-chief in France, while in his audience is a United States admiral who commands a large destroyer flotilla in European waters. Preserve this picture, which was taken on Independence Day, for it holds more than passing interest. The tomb of Lafayette is the most hallowed spot in Europe to Americans, the fame of Joffre will live for all time and it is within the realm of probability that the name of Pershing will be written with those of the world’s greatest soldiers. Scenes such as this are epochs in history. Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18df5dc749

The Mexican problem was now practically settled, the punitive expedition was withdrawn, and the army once again marked time on the border, while the fearful European war turned the once peaceful soil of France into a veritable quagmire of blood.

By diplomacy and evasion, President Wilson endeavored to keep the United States out of war, but it was of no avail. The gods willed it that the German people would go stark, staring mad; would disregard all laws of civilized warfare, and would drag the United States into the conflict by sheer barbarity and lack of decency for civilized conduct.

When Congress had admitted that a state of war existed with the German Government, troops were immediately dispatched to Paris, and from thence to the front. With them, as Commander, went Pershing. Stern, square-jawed, erect, soldierly-looking, he was a splendid and fitting example of the perfect military man produced by the West Point Military Academy.

When asked to make an address, he told the French, that, as the representative of a Government which liked to see things done in a business-like manner, he was there to help to win the war as speedily as possible. And, still later, he made the remark:

“Lafayette, we are here!”

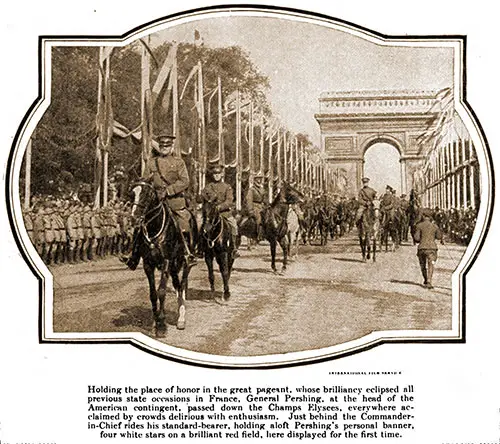

General Pershing Heading Down the Champs Elysées in Paris. Holding the Place of Honor in the Great Pageant. Whose Brilliancy Eclipsed All Previous State Occasions in France, General Pershing, at the Head of the American Contingent, Passed down the Champs Elysées. Everywhere Acclaimed by Crowds Delirious with Enthusiasm. Just behind the Commander-in-chief Rides His Standard-bearer, Holding Aloft Pershing's Personal Banner, Four White Stars on a Brilliant Red Field, Here Displayed for the First Time. Photo by International Film Service. Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18df6face7

He meant by this that the debt which the United States owed to France because of the assistance given the struggling colonies by Lafayette and Rochambeau in 1775 1776 was now to be repaid, and right glad was the United States to repay that debt tenfold. For when Uncle Sam was in knee-breeches, the French had helped the poor boy who was being spanked by his big brother, Great Britain.

Now, the little boy had grown to be a very powerful man and the rich and prosperous old fellow was all ready to help out those who had given him assistance when he was poor and weak. A fine speech, General Pershing, was that you made, and all people are grateful to you for expressing the chivalrous sentiments of the vast majority of those who live in the United States.

The soldiers of America made a good impression. They are lean, spare young men, all athletic and quick- thinking. Received with tremendous enthusiasm by the French, they were soon able to show what stuff they were made of on the battlefield, and went forward with such superb courage and élan, that a French General said that the only fault he had to find with the Americans was they were too brave and exposed themselves with a too great recklessness and dare-deviltry.

As for the victories at Château-Thierry, Verdun, and the capture of the St. Mihiel Salient with ten thousand German prisoners, we cannot say that it was Pershing himself who did this, no — it was the United States soldiers who did it.

Yet they were well directed by their keen-eyed General, and all acknowledge that he has well represented the country which dispatched him to the scene of conflict. As for his men, they fought with a superb courage and heroism.

Inheriting a love for sport from their English forebears, the Americans are naturally an athletic race. Fighting a battle is like playing a game of football, and it is thus natural that the United States soldiers took to fighting with a zest that was unusual. The Germans, on the other hand, are not a sport-loving people, their interest in athletics being mainly directed to gymnastic exercises.

In all of Germany there are no inter-city games of any variety, or any indulgence in sport for sport’s sake as in the United States and in England. The Germans have been made to become soldiers, and all of their youthful activity which American and English boys put into sport is utilized by them in drill and military exercise. The Kaiser and his advisers made a race of docile soldiers and not a race of sportsmen.

General Pershing is a splendid rider and has always excelled as a cavalryman. He is also a good shot and is fond of bird shooting. Like all Americans, he has a keen sense of humor and delights in a good joke, even at his own expense. No one played more practical jokes than he did when at West Point, and he has never lost his delight in the comic side of life.

There is a keen twinkle in his clear eye which denotes the man of humor, and no one can laugh with more gusto than can this leader of the greatest army which Uncle Sam has ever put into the field.

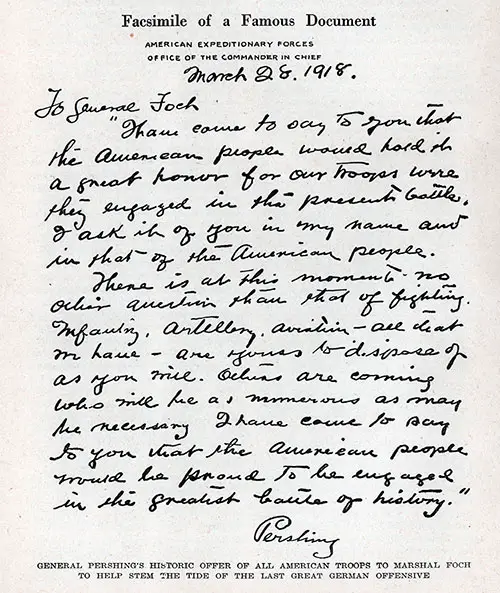

Fascimile of a Famous Document, a Handwritten Letter from General John Pershing to General Foch dated 28 March 1918. It was General Pershing's Historical Offer of All American Troops to Marshal Foch to Help Stem the Tide of the Last Great German Offensive. Current History Magazine, May 1919. GGA Image ID # 18df985058

When his massive army of American troops arrived near the firing-line in France there was a crisis in the German offensive, so, upon March the 28th, General Pershing placed at the disposal of Marshal Foch, who had been agreed upon as Commander-in-Chief of the Allied armies, all of the forces of the United States, to be used by him as he might decide. The first American division was, therefore, transferred from the Toul sector to a position in reserve at Chaumont en Vexin. Ten American divisions were sent to the British army area, where they were trained and equipped.

On April 26th the 1st Division went into the firing line on the Montdidier sector on the Picardy battlefront. The Americans, confident of their training, were eager for a brush with the Germans.

On the morning of May the 20th this division attacked the commanding German position, in front, taking the town of Cantigny with splendid dash and spirit. Here they held firmly against the Prussian artillery. This brilliant action had an electrical effect upon the Allies, for it demonstrated the excellent fighting qualities of the Yanks, and it showed that the vaunted Prussian troops were not invincible.

After this battle the Germans made a mighty thrust at Paris, which was their last and most strenuous effort to reach the goal of their ambition. Aiming at Château-Thierry, division after division was hurled upon the French lines which stood in the path of the German invasion.

Every available man was placed at Marshal Foch’s disposal, and the 3d American Division, which had just come from their preliminary training in the trenches, was hurried to the Marne River. Its machine-gun battalions preceded the other units, and, starting for the firing line, were soon in active engagement with the oncoming German divisions. Opposite Château- Thierry these troops successfully held the bridgehead, inflicting terrible slaughter upon the Prussian host.

The brunt of the fighting, during the early part of this affair, was done by the Brigade of U. S. Marines, commanded by Major General James G. Harboard, U. S. A., under whom — as regimental commanders — were Colonels Neville and Catlin. The Major-General commanding was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in France, May 15th, 1917, and had a fine record as a soldier, from the time that he had graduated from the Infantry and Cavalry school in 1895, to the present moment.

He had served in the Spanish War with distinction and, although a volunteer, had been mustered out and appointed a 1st Lieutenant of the 10th U. S. cavalry, July 1st, 1898. He had served as Assistant Chief of the Philippine Constabulary, with the rank of Colonel from August 18th, 1903, to January 1st, 1914. He was to receive the Legion of Honor for his gallant defense of Château-Thierry.

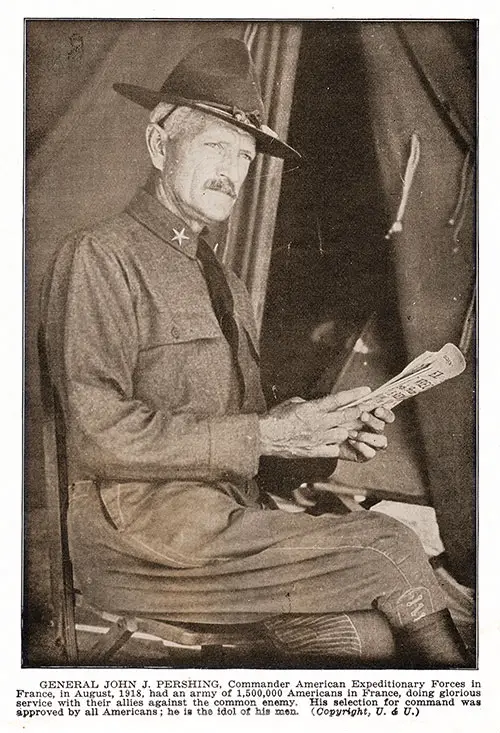

General John J. Pershing, Commander American Expeditionary Forces in France, in August, 1918, Had an Army of 1,500,000 Americans in France, Doing Glorious Service With Their Allies Against the Common Enemy. His Selection for Command Was Approved by All Americans ; He Is the Idol of His Men. The World's Greatest War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18df9d648e

Colonels Catlin and Neville had both graduated in the same class at the U. S. Naval Academy — that of 1886 — and had both had varied service under the Stars and Stripes. The former, now a Brigadier General, had commanded the Marine guard of the Maine, when blown up in Haifa harbor, prior to the Spanish-American war.

He had swum ashore and had been promoted to be Captain, shortly afterwards. He had served in the army of occupation in Cuba, had received a Medal of Honor for gallant conduct — under fire — at Vera Cruz in April 1914, had been sent to France in charge of the 6th Regiment of Marines, and, when directing the advance of the lighting men of the sea, was badly wounded, on June 6th, 1917.

Colonel Neville — now a Brigadier General — had been appointed a 1st Lieutenant in the Marine Corps, July 1st, 1892 had served in the marine battalion in Cuba, and, on June 13th, 1898, had been appointed Captain by Brevet, for conspicuous conduct at the battle of Guantanamo, Cuba. He had served in China, during the Boxer rebellion, had been made a Major, December 9th, 1904; was in the Cuban army of occupation in 1906, was in charge of a brigade of Marines in Panama, in 1910, was a Lieutenant-Colonel at the battle of Vera Crus in April 1914, and bad been given a Medal of Honor for conspicuous courage at this Mexican affair, April 21st, 1914. For two years he had been in charge of the American Legation Guard in China, and from that country, he had been sent to France in December 1917, where he was placed in command of the 5th Regiment of Marines. For his gallant and meritorious services to France he was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French Government.

As the Marine Brigade was the first to strike the enemy in this portentous battle, and, as it suffered most heavily in losses, I will therefore devote myself to a description of the attack, based on the very excellent letter of Major Frank E. Evans to Major General George Barnett, Commandant of the U. S. Marine Corps. This is in no way to detract from the honor due the entire American fighting force in this sector, for all should be lauded for their daring and determination; a determination which seemed to be inspired by the spirit of the old crusaders, and which has fortunately ended in a victory for the Allied arms.

The Marines had never before faced such odds, nor had they been confronted with such a crisis, for, were the Germans not stopped, they would soon be in Paris, and it would be dark for the Allied cause. All the officers and men felt this, and determined to give a good account of themselves. They left their camions near Paris to march to the sound of the guns.

On the way to the front farm-wagons lumbered along with chickens and geese swung beneath in coops, filled with what the retreating farmers could gather together, within, and by their sides walked cattle driven by boys of nine or ten years of age.

The mothers of these children crept along — weeping bitterly at the change of fortune which had forced them to leave their happy homes — while little tots trotted past near their mother’s skirts.

As the Marines advanced, the horror of war became engraved in their very souls, their eyes seemed to burn with a crusading fire, and, as an old lady with snow- white hair came to view, seated like a noblesse upon the top of piled-up boxes and mattresses, in the best farm-cart, a mighty shout went up for, “ The Grand Duchess, may she again be living in her devastated home.”

The town of Meaux was crowded with refugees; everywhere was confusion, disorder, retreat; the flotsam and jetsam of war before the descendants of Attila the Hun.

The road was a living mass of men, women, children, soldiers, horses, teams, bales, boxes — confusion.

French dragoons trotted by with their lances at rest with officers as trim as if they had just left the barracks; trains of ambulances lumbered past, guns of all sizes — from the 75’s to the 210's — cars carrying staff officers whizzed by in a trail of saffron-colored dust, which coated men, wagons, horses, with a gray pall of mummified dirt.

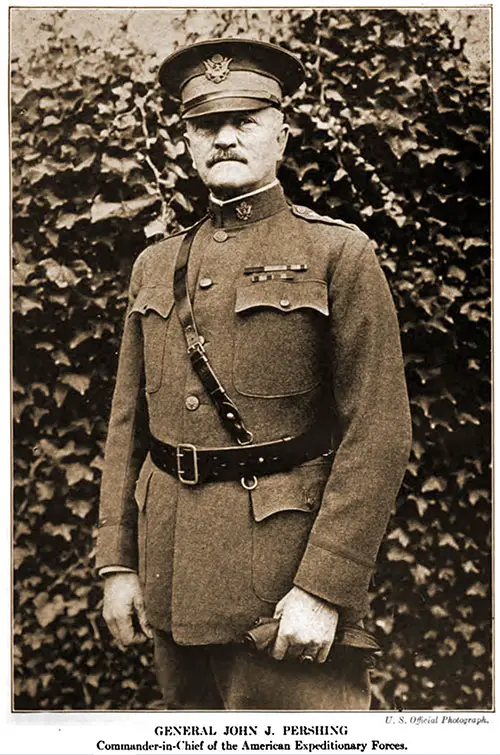

General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces. US Official Photograph. America's Part in the World War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18dfa3c5f1

Late in the evening the Marine Brigade swept to the right, defiled from the road in the direction of the river Marne, and bivouacked on the roadside or in the fields. They were seven kilometers back of where they were to advance into line of battle, and, although orders were found to go into action that evening, the men were so badly in need of rest that it was decided to camp for the night.

The French then determined to let the Americans see what it was to fight the Boche next afternoon. The Poilus were hard pressed in front and they needed assistance badly; numbers of fugitives streamed to the rear, crying out: “Look out, Yanks, the Boche can fight like wild men! Look out, Yanks. You will get it in the morning!”

It was the first day of June, there was death and fire in the valley of the slow-winding river Marne; French videttes came into camp saying that the Boche had fought them with machine guns and hand grenades — they were advancing with great élan and courage, and that their best troops — the Prussian Guard — were in front. On the following day the French began to retreat, tired out with incessant fighting and greatly outnumbered, and that afternoon — by a prearranged plan — they dropped back, passed through the line of the Americans, and thus made the Marines the front line. On the right were the French. With one company, only, as a regimental reserve, the Soldiers of the Sea awaited the battle with calm determination.

At five o’clock in the afternoon the Germans attacked in force. Across a field which looked as flat and green as a base-ball diamond they came swinging on, in two thin gray columns. Shoulder to shoulder, rank on rank, in silence and without confusion, the Kaiser’s men faced a withering fire from machine-guns and rifles of the Americans and French.

Overhead burst thin clouds from shrapnel, — the gunners did not seem to have the proper range — then they found it, and great gaps began to appear in the gray lines. It looked as if great patches of white daisies had begun to grow upon the green fields where those bull-doggish columns were moving.

The white patches from the bursting shrapnel would roll away, and great holes could be seen in the gray masses of Germans. A hail of rifle-fire was being poured into them — no human beings could ever withstand such a rain of shot and shell. The columns staggered — stood still — ha! They broke! Hurray! they were retreating.

An aeroplane was hovering in the air, watching the battle from a safe distance, and, when the French and American gunners got the range of the Hun lines, the operator signaled down “Bravo.” As the Boche broke cover and ran to the woods for protection, they could be followed by ripples in the green wheat through which they coursed in their flight. Once in the woods they hurried from view — a mighty shout went up from the thirsty throats of the Marines — first blood had been in favor of the men from over the sea, and, as the cheer welled over the wheat, a thrush caroled a song from a linden tree.

The French crowded around in order to congratulate the Americans, for, that men should fire deliberately and use their sights to adjust the range, was beyond their experience. The rifle-fire had had a telling effect upon the Germans, for it was something that they had not counted on.

They had steadily pushed back the weakened French — they expected to get to Paris — when they had run into this stone-wall defense. When they attacked, the Germans did not know that the Americans were in the front line, and they were astonished at the way in which the defense had stiffened up; they realized that their days of triumphant progress were to be no more.

It was only the beginning — the real fireworks broke on the sixth day of June — when it was decided to make a general advance upon the front of the entire Brigade, in order to recover territory and straighten out the lines. The 23d Infantry had been brought up to reinforce the Marines, and these fresh troops had been placed upon the right flank.

In front of the eager troops was the Bois de Belleau (Wood of Belleau), and the little village of Bouresches. It was determined to attack at 5 pm which would seem to be late in most countries, but, owing to the long twilight in France, this was an excellent moment to advance. The artillery preparation was short, and, before the Yanks pressed forward, one of the platoons of the machine-gun company laid down a barrage. When all was ready, the men leaped from their trenches and went over the top.

The woods were fairly alive with machine-guns, and, as the boys rushed forward, these spat a deadly fire into their ranks. On the left, the Germans fought stubbornly, doggedly; they mowed down many a youthful and energetic American, yet, about 9 pm, or after four hours of the struggle — a runner came in with word that the left had advanced as far as the right, and that the worst machine-gun nests were surrounded upon a rocky plateau. Word was also brought in that Colonel Catlin had been wounded, and one Marine officer ejaculated:

General John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) by R. J. Hodshon, G Company, 346th Infantry. GGA Image ID # 18dfc77779

“Too bad! Too bad! The bottom of the war has dropped out!”

The Colonel was standing up in a machine-gun pit with his glasses raised when a sniper drilled him clean through the right of his chest. He fell, was carried to the rear, and moved back to a dressing station. As Captain Laspierre went over to report to Captain Feland, a shell burst near him and he was shocked and gassed. Thus two marine officers were done away with in a few moments.

The removal of Catlin was a great loss, as he was a man familiar with all that had to be done, had a complete grasp of military situations, and was looked up to by both officers and men.

The fighting now was furious, and, as shells exploded above the dark woodland, both Germans and Americans grappled with each other in a deadly embrace. As darkness began to fall, word came to Marine Headquarters that the village of Bouresches had been captured; that the Americans — racing through a terrific barrage — had entered the streets, where, after desperate street fighting, they had driven off the tenacious Germans. Prisoners began to stream back of the lines — grinning — as if delighted to be taken, and, with their hands in the air, murmured: “Kamerad! Kamerad!” As darkness fell, the fire from spitting guns reddened the skies, and dull roaring came from the exploding shells.

Meanwhile, spitting telephone and telegraph wires sent back word of what the American boys were doing, and, far to the rear, the anxious Parisians, learning of the smashing advance by our men, shrugged their shoulders, smiled — even laughed — saying to each other: “Voila! What did I tell you of these Americans? They are true fighters. The aid which we gave them with Lafayette will now be doubly repaid.”

And far, far, away, in the fresh, new land of America, the newsboys called the EXTRAS, and the eager purchasers read how the Marines were stemming the torrent at Belleau Wood. Men and women gathered in crowds — silently read the news, with drawn faces, anxiously awaiting the still later dispatches, including the casualty list.

The fighting went on next day, and dawn saw American and German in another furious embrace. Machineguns spat, shrapnel screeched, big guns boomed, but on, on went the Yanks, on, on, right through the hail of lead and over the German trenches. So fierce was the attack that the Soldiers of the Sea lost nearly their entire force — of eight thousand engaged, all but two thousand were either killed, captured, or wounded. Prisoners streamed through the French and American lines.

One Marine officer, Timberman, charged a machine- gun nest at the point of the bayonet and sent in seventeen prisoners. Meanwhile, word came back to send up ammunition, so a truck raced down the road for Bouresches, guided by Lieutenant W. B. Moore — the Captain of the Princeton track team, and half-back of the football eleven. A fierce counterattack upon the town was repelled, and, as the Boche sullenly retired in the direction of Germany, they were greeted by victorious cheering from those who had survived this holocaust.

The Americans had captured Belleau Wood, Château- Thierry, and the smoking village of Bouresches. Grimly they watched the puffing lines of German fire, and grimly they took account of their many wounded, while struggling onward came the great guns to shell the Boche earthworks; and Pershing, far in the rear, yet vigilant, aggressive, confident that his boys would live up to their reputations of dare-devilish fighters, received the warm congratulations of the French.

General Pershing will Rank in History with the World’s Greatest Generals. Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 18e0200074

His boys had well sustained the athletic supremacy which they had always won for the old flag in athletic contests at the Olympic games. They had shown themselves to be as competent to wage war as they had been to run the quarter mile.

The Boche had had the fight knocked out of him and he admitted it. The artillery had simply pulverized the German earthworks and stone defenses. The last draft of prisoners taken had been cut off from supplies for three days by the incessant and rapid fire of the Yankee gunners. The prisoners varied in size: some being fine big chaps — apparently retired farmers — but others being undersized and weak-looking, many of them very young.

At first the Germans thought that they were opposed by Canadians, but this illusion was dispelled, the last lot of captives saying that they knew the Americans to have about seven hundred thousand men, and that they did not wish to fight them, for the Yanks gave them no rest, and their artillery punished them terribly.

Many diaries were taken from both the dead and living, and these started off with “Gott Mit Uns,” and boasted of what the Germans were going to do to the Americans. Then they proceeded to tell of lying in the woods under a hell of steel, and they spoke of the big, brave Americans who seemed to know no fear. The papers would usually end with the statements that they knew themselves to be defeated, for, with the vast horde of fresh Americans in the line, it would be impossible for them to keep up their drive.

As the Germans indulged in gloomy forebodings of coming disaster one Yankee officer tipped this message to the rear:

“The chickens have arrived, and they are all scratching.”

Not only were they scratching, but the cocks were soon to be all crowing. The five days of fighting had resulted in the capture of the village of Barzy-le-Sac by the First Division, who also had gained the heights above Soissons. The Second Division took Beau Benaire farm and Viceizy, and, upon the second day of their advance, took Tigny. Both Divisions captured seven thousand prisoners and over one hundred pieces of artillery.

As the Prussians were being driven back in this sector, to the south — at St. Mihiel — combined French, English, and American land and air forces started another big drive. At 5 am on September 12th, seven American Divisions advanced, assisted by a limited number of tanks, preceding this attack by four hours of artillery preparation.

As at Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood, the Americans here fought like demons. Preceded by groups of wire-cutters and other scouts, armed with Bangalore torpedoes, they went through the successive bands of barbed-wire which protected the German front-line and supporting trenches in irresistible waves and on scheduled time.

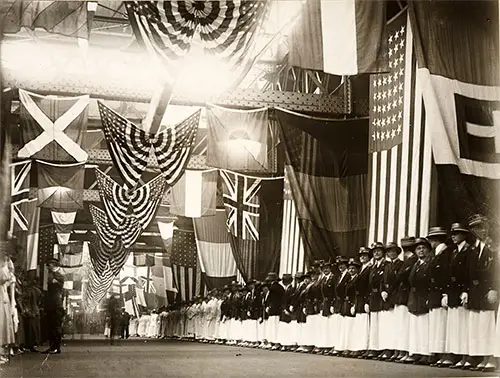

General Persing Arrives 8 September 1919 at Hoboken. a View of the Pier, Decorated la Honor of the Returning Commanding General of the U.S. Army, General John J. Pershing. at the Side, Red Cross Workers Are Lined up to Salute the General as He Leaves the Leviathan. Photograph by Western Newspaper Union. National Archives and Records Administration 165-WW-94-A-1. GGA Image ID # 186b6ee1c3

Half hidden by fog, the gallant Yanks quickly routed the enemy, already demoralized by the furious artillery fire. At the cost of only seven thousand casualties, mostly light, the Americans captured ten thousand prisoners, four hundred and forty-three guns, a great quantity of war material, and released the inhabitants of many villages from the grasp of the terrible invader. The battleline was soon established in a position to threaten Metz.

General Pershing, in his official report, says that: “The signal success of the American First Army, in its first offensive, was of prime importance. The Allies found that they had a formidable army to aid them, and the enemy learned formally that he had one to reckon with.”

In fact, the great victory at the St. Mihiel salient had prepared the way for the supreme effort of the Allies to win a conclusive victory. The American army moved forward at once to its greatest battle — the fight at the river Meuse.

This action began on the night of September 25th, when the Americans took the place of the wearied French on this long sector. The attack opened on September 26th, and the Americans drove through all the wire entanglements in their path, across No Man’s Land, and took all of the enemy’s front-line positions. They pushed steadily onward, and eastward.

On November 6th, a Division of the 1st Corps reached a point on the Meuse opposite Sedan, the strategic goal for which the French Commander, General Foch, had aimed. Now, the Yanks had cut the main line of communications of the Kaiser’s mighty forces, and nothing but an armistice or a surrender, could save the German army from complete disaster.

Forty German divisions had faced the overseas fighters in these battles near the river Meuse. Between September 26th and November 6th the Americans took twenty-six thousand and fifty-nine prisoners and four hundred and sixty-eight guns. They had put a final nail into the coffin of the Kaiser and his armies of would-be world conquerors by their aggressive advance.

And that General Pershing is appreciative of the valor of his noble “boys” may be seen from the following:

“I pay the supreme tribute to our officers and soldiers of the line. When I think of their heroism, their patience under hardships, their unflinching spirit of offensive action, I am filled with emotion which I am unable to express. Their deeds are immortal, and they have earned the eternal gratitude of their country.”

So, General Pershing, we salute you! Chosen to command an army of honorable deliverers, who have been truthfully spoken of as Pershing’s Crusaders, you have seen that your men fought fairly, conducted themselves cleanly, and have dealt with innocent non-combatants with chivalrous courtesy.

Arriving in stricken France at the propitious moment, your troops, by their dash and spirit, have broken the backbone of the invading Boche, have driven the Germans from Alsace and Lorraine, and are now policing this territory, once the property of France, and soon to be returned to its former owner, as is the wish of the French people, and the desire of many of the inhabitants of this border country.

Conducting yourself as a man of high moral and intellectual courage, you have set a splendid example for future officers to emulate, and you have brought both credit and distinction to the flag of the United States, which has never been unfurled in battle for an ignoble cause, and which will always, we trust, be the symbol of justice, equality, and fair dealing to all people, whether they be strong and prosperous, or weak and poverty-stricken.

Charles H. L. Johnston, Famous Generals of the Great War Who Let the United States and Her Allies to a Glorious Victory, Boston: The Page Company, 1919.