General Joffre - Hero of The Battle of The Marne

General Joffre Commanded the French During the First Seventeen Months of the War, Was Then Retired as Marshal of France, and in April, 1917, Came to America as a Member of the French War Commission. He Was the Idol of the Soldiers Who Spoke of Him Affectionately as "Grand-Papa" and "Our Joffre." His Ringing Message to the Army Before the Battle of the Marne Will Long Be Remembered: "Cost What It May, the Hour for the Advance Has Come; Let Each Man Die in His Place, Rather Than Fall Back." Photograph © International News Service. History of the World War, Volume 1, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18bdd33e98

“Papa” Joffre

The French army had been retreating for weeks before the onrushing Prussian hordes. The Poilus had, therefore, begun to wonder how much longer they would have to make this retrograde movement, when the following order was read to them:

“Soldiers:“ At a moment when a battle, on which the salvation of your country may depend, is about to begin, you must remember that this is not the time for retrospective glances, for all our efforts must be employed to attack. An army that cannot advance, must, no matter what the cost, maintain the territory won, and die rather than retreat.

(Signed) “Joffre.”

Fired by these stirring words, and by the still more portentous fact, that, should they not beat back the Hunnish avalanche, the city of Paris would soon be in the hands of the invader, the French soldiers turned to fight the grimmest battle which their countrymen had engaged in since the fierce conflict of Sedan, in 1870.

In command of their entire force was a man who had been born at Rivesaltes, in the southern part of France, and near the Pyrénées mountains, January 12th. 1852.

The son of a cooper, Joseph-Jacques-Cesaire Joffre, the future Generalissimo of the French army was one of eleven children, of whom but three—two brothers and a sister, Madame Artus, the widow of a Captain of artillery—remain alive to-day. The Joffre home was humble, plain, and inartistic; such a home as a man of very moderate means would occupy.

The childhood of General Joffre differed little from that of thousands of other boys and girls who went to school and played with him in the streets of Rivesaltes.

Young Joffre was a silent boy, a fair scholar, but neither brilliant nor over-industrious. It seems that he lacked the ability to make himself popular with other boys. He was an obstinate child and preferred lonely rambles to play with his schoolmates.

“My mother used to say that she remembered the general’s mother saying that, when a baby in the cradle, the general never cried,” declared several old residents of Rivesaltes. At any rate, all of the great soldier’s schoolmates remember better than anything else his unwillingness to talk, his peculiar gift of silence, which, in later years has come to be known as “Joffre’s taciturnity.”

France now needed men for its army, for, during the revolutionary period, the nobility had been decimated and exiled. The army now became a great democratic institution, and the French middle class filled the different training schools with their young men.

The future career of little Joffre was decided at a family council, and it was there determined to send the boy to Paris where he was to prepare for the Polytechnic. So, at the age of fifteen and a half years, Joseph Joffre left his paternal home. This was in 1869. A year later he entered the army that defended Paris against the besieging Prussians.

Beaten and humiliated at Sedan, Napoleon III capitulated to the Prussian King, and, when the exultant Germans advanced upon Paris, young Joffre was given an emergency commission as a lieutenant of artillery.

He took his post with one of the siege batteries hastily formed for the defense of the capital against the dreaded foe. As you all know — Paris fell — the Prussians exacted an indemnity of $15,000,000 from the bleeding city, and marched back to Germany richer and more overbearing than when they came.

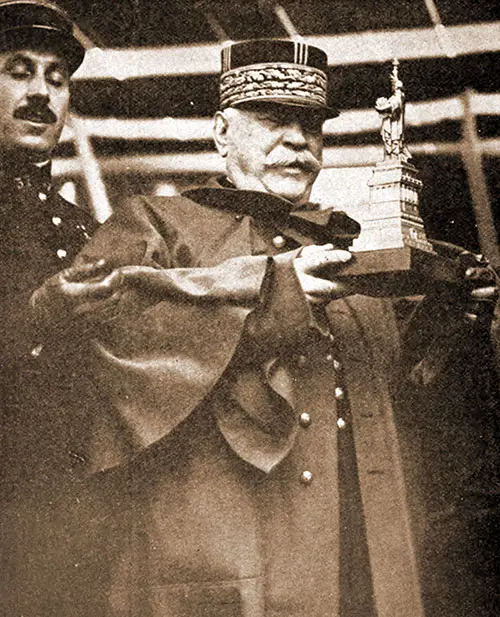

Marshal Joseph Jacques Joffre. Marshal Joffre Is Holding the Golden Miniature Liberty Statue Presented to Him When He Visited New York City in 1917. Photograph by Underwood & Underwood, New York. Lest We Forget, 1918. GGA Image ID # 18bfe264c0

After the war young Joffre gave up his commission as a gunner, returned to the Ecole Polytechnique to complete his course of study, and left during the following year, 1872, having the rank of lieutenant, attached to the 2nd Regiment of Engineers.

He was now twenty, and his marvelous ability to manipulate figures rapidly and accurately, his thorough knowledge of the higher mathematics, his logical mind, and his great common sense, soon secured him a foremost place among his fellow officers.

The Paris defenses were much in need of improvement at this time, and Lieutenant Joffre was now employed in the occupation of rendering them more secure.

In 1876 Marechal de MacMahon, who was the President of the Republic, made a personal and thorough inspection of the work already accomplished by his officers, and, being pleased with what had been done, took occasion to congratulate those who had made such excellent progress.

Turning to a squarely built, unassuming sapper, who was standing near one of the fortifications, he said, in an abrupt manner: “I congratulate you, Captain Joffre, which was all.

Lieutenant Joffre was astonished, for he little expected the unsought-for promotion. Yet this was a splendid acknowledgment of his worth and energy, and never was honor more justly deserved or more modestly borne.

Without more ado he turned back to his work of perfecting the defenses of Paris, and labored so persistently that in five years the city had been made practically impregnable; or as impregnable as it was humanly possible to make it.

Joffre, in fact, became a master in the art of building fortifications. His work was noticed, and, when Admiral Courbet telegraphed from Kelong—a port in the Island of Formosa—for a French officer who understood thoroughly the way to dig trenches and to erect forts, Joffre was very naturally chosen for the task.

Kelong had been occupied by the French for but one year, yet it was essential that an army of occupation should be placed there to establish French rights and to exclude the growing German influence in the Far East.

To Joffre was to be given the task of making Kelong into a formidable fortress, and so well did he accomplish this duty that he was decorated with the Legion of Honor.

For three years the robust young Frenchman remained in Formosa, occupying himself—for the most part—in effecting a system of housing which was practically perfect.

Under his direction barracks were put up, and they afforded the men such excellent protection against both heat and damp, that many valuable lives were saved which otherwise would have been claimed by malaria or enteric, fever.

In 1888, Captain Joffre returned to France, and on May 6th, 1880, was made Major and Commandant at the War Office in Paris. Soon after this he left Paris for Versailles, where he was appointed Major to the 5th Regiment of Railway Corps.

In this position he acquired a great practical knowledge of the French railways, which was to be of such advantage to him when troops were to be mobilized against the Prussian invasion of 1914.

Promotion now came rapidly for the young officer. On April 7, 1891, he was appointed Professeur de Fortification, or lecturer on the art of science and fortification, at the famous artillery school for officers, the Ecole d’Application at Fontainebleau.

It proved to be an excellent teacher and was so greatly appreciated that many were anxious to have him remain in France in order to give the younger generation of officers the benefit of his extensive knowledge of military science. But Major Joffre had adventure in his soul; he longed to go to French Africa and to know something of the great and mysterious Black Continent.

France has an immense African domain. Upon the western coast of Africa she possesses valuable colonies, which are from north to south: Senegal or Senegambia, French Guinea, the Ivory coast, Dahomey, and French Congo.

Upon the northern coast she has highly prosperous territories, stretching from Tunis to Morocco. Forced to retire inland to inaccessible regions, the unruly native tribes are a perpetual menace and a source of grave danger to the peaceful native population in the interior.

It has been one of the duties of the French army to accomplish the task of civilizing the country and of chastising the natives. Also of building railroads from the coast to the interior.

In December 1892, Major Joffre landed upon Dakar’s busy quay, and, in 1893, he was surveying the lines for a railroad to run from Kita to Bammako.

His stay upon the scene was short, but it is largely due to his influence that the Senegal-Niger Railway is a success to-day. At this time the natives in the interior were getting unruly, so in the following year Major Joffre was asked to take command of a column which was to march from Segu to Timbuktu.

This expedition consisted of fourteen French and two native officers. Twenty-eight French and three hundred and fifty-two native non-commissioned officers and men, about two hundred pack horses and mules and some seven hundred native carriers.

The Frenchmen and native assistants were to follow the left bank of the river from Segu to Timbuktu, where a Colonel Bonnier was to receive them.

They were expected to invite the native chiefs, who had not already made submission to the French flag, to join the column and come to Timbuktu. If they showed themselves to be unruly, there was to be a fight.

Leaving Segu on December 27th, 1893, Major. Joffre and his party reached Timbuktu on February 12th, 1894. Their march had not been an easy one, for the population of some of the villages upon the way had been distinctly hostile and the necessary supplies had to be taken by force or cunning.

On several occasions, a number of natives, called Tonaregs, had attacked the expedition with great daring, and, although they had attempted to kill many of the French troops, they had not succeeded in their attempt. Only one French sergeant had been wounded.

When nearing Timbuktu Major Joffre learned that Colonel Bonnier and most of his men had been surprised and murdered by the Tonaregs at Taconbao, early in January; a feat which had emboldened all of the other native tribes and had made them eager to take up arms against the French.

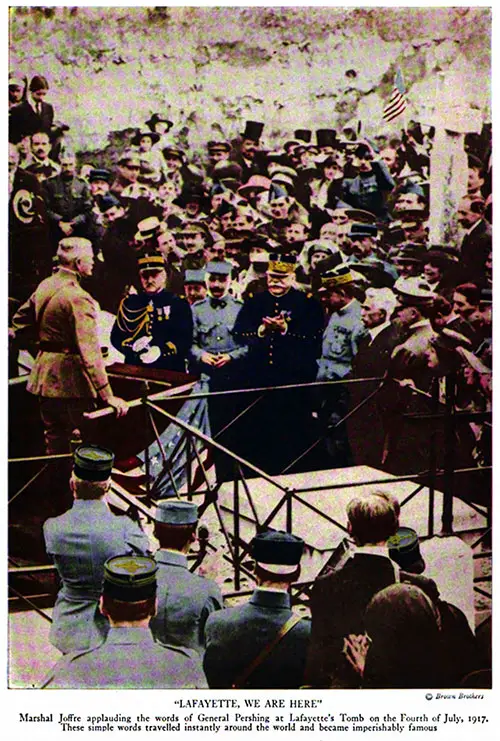

"Lafayette, We Are Here." Marshal Joffre Applauding the Words of General Pershing at Lafayette's Tomb on the Fourth of July 1917. These Simple Words Traveled Instantly Around the World and Became Imperishably Famous. Photograph © Brown Brothers. The United States in the Great War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18dd82db20

So, without waiting for orders or instructions from the authorities at home, Joffre at once abandoned all idea of returning to Kayes. Instead, he lost no precious moments in taking such measures as would enable him to deal a crushing blow to the natives, and thus to restore confidence to the peaceful population, which had begun to doubt the ability of the French to cope with the hostile invaders.

For six months he and his soldiers now fought and chased the hostile Tonaregs, and so successfully was this done, that, at the end of that time, the fighting tribes had been practically annihilated and the inhabitants of Timbuktu and of the river districts were at last free from all danger of pillage and rapine.

Communications with the exterior were re-established and prosperity soon returned to the desolate regions. So well was he thought of at home that the appreciation of his conduct was publicly acknowledged by the gazetting of his name as Lieutenant Colonel. This was on March 6th, 1894.

The work in Sudan was difficult, but Joffre seemed to enjoy it, and, when told to report again in France, he was right loath to give up his labors.

Still, a soldier has to do what he is told to do, so, returning to his native land, he was appointed Secretary to a learned body known as the Commission d'Examen des Inventions Interessant les Armees de Terre et de Mer,— a committee of experts and scientists whose mission consists in the examination of the claims of inventors and of the merits of all inventions and discoveries likely to be of use to, and add to the efficiency of France’s land and sea forces.

Joffre retained this post for four and a half years, and, of course, gained a vast store of technical knowledge which was of much assistance to him when, later on, he was called to the stupendous task of whipping France into shape for the terrible battles with Prussia, for the liberty of her people.

On November 10th, 1899, the studious and taciturn soldier was appointed to the position of officer commanding the 5th, or Railway Regiment, at Versailles, and on December 23rd, 1899, was sent to Madagascar, that fertile spot off the coast of Africa which has been the property of France for so many years.

Here he again used his engineering skill in making a system of defenses and was as successful as at the chain of fortifications around Paris. Less than two years after his arrival at this distant post, Joffre had, by hard work, ability, and an indomitable tenacity, perfected a splendid system of fortifications about Diego Suarez.

His valuable services to the mother country were officially recognized by his promotion to the rank of Brigadier General, on October 12th, 1901.

Returning to France from this African possession, the newly appointed general was given command of the 19th artillery brigade. In July, 1903, he was raised to the dignified position of Commandant de la Légion d’Honneur, and, shortly after this, was told to take supreme control of the whole corps of engineers. In March,

1905. he was promoted to the rank of General of Division, but remained at the War Office until January, 1906, when he was placed in command of the 6th Infantry Division. In May 1908, he was put at. the head of the 2nd army corps.

Realizing, at this time, that war with Prussia was imminent, the general set about to drill the army in preparation for the mighty conflict which he knew would be soon upon the people.

By word and writing he endeavored to prepare the mind of the French for the war which all knew to be inevitable. “The French,” he said, “should have a tenacious purpose to win. They must have victory written in their very soul.”

“The material organization of an army,” he added, “perfect though it may be; its understanding no matter how highly developed, will be insufficient to insure us a victory, if this army, strong and intelligent as it may have become, will lack a soul.”

Napoleon the great said many a good thing, and one of the best remarks which he ever made, was: “The primordial virtue of a general commanding an army is his character.”

General Joffre is a man of character, and this force has been felt throughout the ranks of the entire French army, until every soldier in the trenches, every trooper in the held, owns, as a part of himself, this precious gift.

A strict disciplinarian, he became the idol of the army. “A well-balanced mind, — a well-balanced soul,” is the verdict pronounced upon him by one of France’s most eminent thinkers.

Fairly tall and quite broad, the figure of General Joffre is massive and strong looking. His head is large, his hair is thick and wavy, his eyes are deep-set and grayish blue. His neck is short, and his broad shoulders give him the appearance of great strength.

His gray eyebrows are very long and bristly; his forehead is wide; his nose straight and fully developed. His lower jaw is powerful, but not brutal, his chin round and clean shaven.

Free from all vanity, simple of dress and habit, scrupulously fair and strictly just, eminently sincere and loyal to his friends, his soldiers, and his country, Joffre is loved and trusted by all who know him.

His soldiers have a blind confidence in his ability, and thus — when after weeks of retreat, although exhausted and fatigued — they heard the voice of Joffre cry out: “Halt! and Fight!” all turned heroically and willingly to drive the Prussian invader from the soil of the beloved country.

When Prussia declared war on France and her soldiers crossed into Belgium, Joffre was ready. Years before the advance upon Paris he had selected the line of the river Marne as the place at which in the event of a German invasion a great battle should be fought.

Here he halted the French army and here is where he said to his men, “Now is the time and the opportunity to save France; let all advance who can, let all die where they stand who cannot advance! ”

His words raised the spirits of the weary, march-worn soldiers, and his message sank deep into their hearts.

It was the morning of September 1st, 1914, and the sun shone hazily down upon the great surging masses of men who faced each other along the slow-winding Marne, soon to meet in a death struggle for the mastery of the soil of France, and to fight the greatest battle of all history.

Years before, Attila — King of the Huns — had come down victoriously from the north, sweeping all before him, and killing and massacring as he came on. He had been met by Aetius and Theodosius, who had signally defeated him, and had sent his greedy, ferocious host of vandals and freeloaders reeling back across the Rhine. Now history was to repeat itself.

Then the wild cries of barbarians echoed over the fair fields of France. Now the growl of great, massive guns; the sudden, short orders of Officers, the grumble of artillery wagons, and the tramp, tramp, tramp of thousands of hob-nailed shoes sounded above the swishing of the river.

Bugles blared, horses neighed, drums rumbled, flags went fluttering up the roads, lancers, with pennons streaming, galloped past, — all was bustle, hustle, excitement — for France and Germany were to meet in the most awesome struggle that ever mortal man witnessed.

The most portentous battle of all History was to he fought out. No wonder that the brow of General Joffre was furrowed with wrinkles.

Turning to a Lieutenant on his staff he had said: “The army has retreated far enough. On no considerations will it fall back of the Seine and the region north of Bar-le-Duc. We will fight here — to the Death.”

The French armies were placed in the field in the relation in which he deemed they would be most effective:

The First Array, under General Dubail, was in the Vosges, and the second army, under General Castleneau, was near Nancy; the Third army, under General Serrail, was east and south of the Argonne in a kind of “elbow,” joining with the Fourth army under General de Langle de Cary. The Ninth army, under gallant General Foch, was next in line, towards the northeast: then the Fifth army, under Franchet D’Esperey, joining with the little British army of three corps, under General Sir John French; and then the new Sixth army, under the brave General Manoury.

General Joffre was at the little town of Bar-sur-Aube, fifty miles south of Châlons, and he there watched — with some concern — the outcome of the clash at arms. On the morning of September the fifth all of the commanders received from him the now historic message:

“The moment has come for the army to advance at all costs and allow itself to be slain where it stands rather than to give way.”

For fourteen days the French soldiers had been falling back before the exultant Germans; the skin was worn off from the bottom of their feet; their shoes were stuck to their toes with blood.

Without rest, or much food, for fourteen days the French soldiers had been ceaselessly engaged. Now was the turn to attack. It MUST be settled here who was to rule France — French or Germans.

Attila had found that the French were no easy men to vanquish. How was Von Hindenberg to find the descendants of those who had driven back the boastful and blood-thirsty Huns in olden days?

The patriotic defenders of La Belle France had marched on scorching roads, with their throats parched, and suffocated by dust. “Our bodies had beaten a retreat, but not our heads,” says one Pierre Lassere, and so — when the clarion notes of the bugle called out "

En Avant and when the stirring words of General Joffre were read to them, the faces of all the Poilus from Paris to Verdun beamed with joy.

The men were worn out with fatigue and with constant fighting, their faces were black with powder-smoke and their eyes blinded with the chalk-dust of Champagne, — yet they roused themselves for a mighty stand and their hearts were filled with faith and hope. La Belle France should and must triumph. En avant! En avant!

It was daybreak of Sunday, September 6th, and, without any disturbance, or bravado, a little, quiet, studious- looking man pitched his tent near a modern Château near the village of Pleurs, — some six miles southeast of Sezanne. He took out his glasses and raked the skyline, — then, turning to his Aides, he said: “Ha, boys! This is fine. The Boche will now turn tail.”

This jolly, little man — studious-looking, though amiable and laughing, was General Ferdinand Foeli.

He had been assigned to the line from Sezanne to Camp de Mailly, twenty-five miles east, by a little south. The slow-moving Marne ran twenty-five miles north of his position.

His men were in many a town and village in front of him, some of them in a clay pocket near the Marshes of St. Gond. His van was north of this marsh. As the little General scanned the horizon he could hear the guns begin to growl.

“The 75’s are barking,” said he. “It soon will be quite interesting.”

Meanwhile General Joffre — far to the south and rear, had been pacing up and down behind his automobile. He had placed Foch in the most important position where the Prussian Guard was to attack.

He knew whom to trust in his vast army, and he wanted to have Foch in the MOST crucial point; so he, too, scanned the horizon with his glass and whistled a tune. It was THE MARSEILLAISE.

All the Generals paced up and down and whistled, — then Bedlam broke loose.

BOOM! BOOM! ROAR! ROAR!

The Prussian artillery threw a perfect avalanche of lead into the French lines and laid down a barrage. Then — with wild cheers of victory, the steel-helmeted Germans charged.

As the day wore on the Prussian Guard drove Foch’s Angevins and Vendeans of the Ninth Corps back beyond the marshes and occupied their positions of the early morning.

So too — on the east of the line, the Bretons were hurled backward by the fearful rush of the invaders, and the Moroccans of the Forty-Second Division had to yield to the bayonets of the yelping German Divisions.

Night was coming on — all along the vast line the French, English, and Moroccans were engaged, and the carnage was fearful. Joffre paced before his headquarters uneasily, for it was bad news that his couriers were bringing him. It was this: “ Our lines have given way everywhere. Foch is in retreat.”

True — Foch’s new army had given ground almost everywhere.

It was sad news, dispiriting news to General Joffre. Here and there an aide drew up in a panting, puffing automobile. Their news was not all the same — near Verdun the Crown Prince was being driven off, at Nancy the valiant D’Esperey was fighting a fierce battle and was moving the Germans backward, on the north, General French with his Englishmen was holding his own stubbornly and fiercely, but alack and a day — General Foch’s men — those who held the pivotal point were giving way. Joffre again whistled The Marseillaise — he would see what the morrow had to bring.

The morning of the next day broke clear, the sun shrouded by the banks of sulfurous vapor which came from the roaring, rumbling guns, belching ever a hail of smoke and shell. Again the Prussian Guard came on after the men under Foch, again they attacked fiercely, and the battle was hand-to-hand.

A little man — a bandy-legged man — walked out in front of his Headquarters in the Château at Pleurs, and made a cautious remark to his aide, who was smoking a cigarette. It was:

“They are trying to throw us back with such fury that I am sure that means things are going badly for them elsewhere and they are seeking compensation.”

Could he have mounted in an aeroplane, he would have seen that he was quite right. Von Kluck was retiring in a northeasterly direction under the fierce attacks of General Manoury’s men; while Von Buelow— who was in front of General Foch — was moving vast bodies of troops from the left of the line.

In the center the Prussians attacked with renewed energy. Such vast numbers of troops were hurled against the French that they had to retire. On Tuesday, the 8th day of September, Foch had to move his headquarters to Plancy, eleven miles south. lie had reached the river Aube, behind which Joffre had said, “We cannot go.”

The right wing of Foch’s army was weak — woefully weak — it was giving way. The wing must be strengthened — but all the reserves were used up — how was this to be done?

On the left of the line was the Forty-second division and Foch appealed to it to save the day. This would leave a gap in the line, but General D’Esperey was begged to lengthen out his own line in order to fill this hole, so that the Forty-second could march to the weakened right and repel the exultant Prussian Guard.

It was 10 o’clock in the evening when General Grossetti — who commanded the Forty-Second — was roused from his bed in the straw in the shell-riddled farm of Chapton. He was handed an order from General Foch, which was: “ Give us aid on the right, or the Prussians will get through.”

The Officer sat up, rubbed his eyes, and said: “Mon Dieu, I can do it. It is all for France.”

Immediately he bestirred himself. The Colonels of the different Regiments were told what must be done; they gave the necessary orders to their subordinates, and — by morning the Forty-Second was marching along so as to be in the line of defense, but they marched none too soon, for the Prussian Guards — with a colossal effort — had smashed through the right of Foch’s line, and, wild with joy, were driving the Poilus before them.

General Foch was smiling, but, beneath that smile was a heart beating with anguish. To Joffre he telegraphed:

“My center gives way, my right recedes ; the situation is excellent. I shall attack.”

Calling his aides to him, General Foch gave the necessary orders to them — they must bear them to the different parts of the wavering line, and all MUST attack.

By ten o’clock, upon that September day, must be decided who would win the Battle of the Marne — by ten o’clock it would be said, France rises triumphant from the bitter defeat of 1870 — by ten o’clock it would be heralded far and wide — the Germans have been hurled back, the descendants of Attila the Hun have fared even as he did at Châlons.

Giving his orders in smooth, low tones, the General turned, lighted a cigarette, and went out for a walk on the outskirts of the little village of Plancy.

His companion — Lieutenant Ferasson of the artillery — was one of his staff, and, as they walked slowly along, they discussed Economics and Metallurgy.

The day was a clear one and the grumbling roar of the guns was interspersed with the rattle of the machine guns, the spit, spit of the rides, and the fierce cries of the fighting men.

Dead and dying lay everywhere, the ambulances were doing great and valiant service, but still the Prussians came on. They were breaking through and thought themselves victorious, when up marched the Forty-Second Division, right into the gap which the Germans believed would let them through to Paris.

The men of this chosen Corps were half dead with fatigue, and their eyes—it is said — were blazing with such intensity of purpose, that the Germans were terrified when they saw these fanatics, thinking them spirits.

At any rate they defiled into line, just when most needed, and blocked Von Puelow's way to Paris. The Prussians wavered. Then — at about six o’clock — they were seen to go backward. Hurrah! Foch’s maneuver had won the day for France.

The setting sun cast shadows across the fields of the Marne when the news was brought to imperturbable Joffre: “Foch has them. Von Buelow is in retreat.”

The General smiled — for the first time in two weeks. Again he whistled the Marseillaise.

Night fell over the awful scene. Dead and dying littered the roads. Horses sprawled everywhere. Ambulances dashed here and there — the great star shells lit up the darkness. Next morning would see who would control the Marne, and the men of the Forty-Second rested easily — they had been fired by the spirit of Jeanne D’Arc.

It was now September 10th, and as the sun rose it shone sodden and gray upon the ranks of the men of the Forty-second, who, pushing onward, fighting grimly, entered the village of Champenoise, where they captured numberless Prussian officers, who, thinking that they had won the day, had gone to sleep snugly in wine-cellars.

On, on went the Forty-second — and — two days later were at Châlons— the Prussians in retreat were fleeing across the Marne. On, on went the French, and, as the German host withdrew, they were shelled busily by the 75’s. Attila had here crossed centuries before, his wild riders of the plains dispirited and woebegone after their defeat at Châlons.

Meanwhile, far in the rear stood General Joffre, stolid, rotund, imperturbable: the essence of what we think a Frenchman is not, and an Englishman is. Aides were bringing good news to him and he was smiling.

“The Prussians are retreating all along the line,” they said. “The Battle of the Marne is ours.”

And near Châlons, a little General, who had been a teacher in the Military School, was directing the crossing of the river by the French armies. He was still talking Economics in his spare moments, and was jesting with his aide, and he sometimes mentioned Metallurgy. This was General Ferdinand Foch.

Many, many years hence, patriotic Frenchmen will put up a statue to the imperturbable soldier who stood behind the vast lines of battle at the River Marne and watched the gallant Poilus battle with the Prussians to a fair-earned victory.

It will bear the name of one who will rank with the great war-time heroes of France: Bayard, DuGuescelin, Ney, Henry of Navarre, Lafayette, Jeanne D’Arc, and Rochambeau.

But I wonder if they will carve on it “Papa ” Joffre, or just plain General Joffre ?

Charles H. L. Johnston, '“Papa ” Joffre' in Famous Generals of the Great War Who Let the United States and Her Allies to a Glorious Victory, Boston: The Page Company, 1919.