Americans Arrive in Paris - Homeward Bound Americans - 1919

Front Cover (Title Portion), To The Homeward Bound Americans by V. Van Vorst, 1919. Printed in France, provides an excellent recap of the activities of the Allied Expeditionary Force (A. E. F.) and their activities in France. GGA Image ID # 17fa62b4c0

Introduction

You are about to embark for the United States as the homeward-bound soldiers of the first American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) that ever crossed the seas to fight foreign soil. At the moment of your leave taking, it is the purpose of this little book to state in a few words what your presence has meant to the French people, to express to you their gratitude, and to briefly recount the part you played in winning the war.

At the most critical moment of the struggle, which had lasted for three years against German imperialism, you came as strong youths into a country where the young had perished. To the weeping, you brought a smile, to those who had been despoiled, your generosity restored hope, to the fatherless children you offered joy. The summing up of these recollections must remain an inspiration to you and to those who follow you in all future efforts.

Often, marching toward dusk, along some valley road in France, you have watched the lights as they began to shine out from the windows of the little farmhouses, while the mists gradually enveloped all but the shadowy

forms of objects almost indistinguishable. Let it be so in your minds when you think of France: remember the innumerable small homes which almost two million men have died to save, and those hearths where a fire still burns, though the poilu who left it will never return.

If any harsh thoughts remain, let the mists enfold all that is not the romance of this war — the drawing together in fraternal love of those who have suffered.

This is the prayer of France. Together with the gratitude of her living, there is the stirring memory of her dead. It carries its message to you as a blessing from those who, because of your gallant sacrifice, shall not have given their lives in vain.

France, Thankful to the American Allies. A ses Allies Amèricains La France Reconnaissante. The Homeward Bound American, 1919. GGA Image ID # 17fd6e8e3c

The Americans Arrive in Paris

Early in February 1915, the Kaiser made his first tyrannical assertion with regard to where he would allow the ships of his enemies and neutrals to pass without being attacked by German submarines.

In less than a week, Président Wilson had protested. His first note declared that he would hold the Kaiser to account if one American ship were sunk or one American life taken. The details of the discussion which ensued are present to the minds of all.

The point maintained by the American Government was that citizens of the United States had the right to travel by sea, where and whenever they pleased, on American, neutral or belligerent ships. To this proclamation, the Kaiser continued to make evasive answers.

In the spring of 1916, after the attack on the Sussex, he promised to modify his illicit attitude. But on January 31, 1917, with his customary bad faith, he declared that all ships attempting to approach the English or Irish coast, or any port in the Mediterranean, would be sunk without warning.

Within forty-eight hours, diplomatic relations had been broken off with Germany. On April 6, 191 7, the war was declared by the United States. This was the greatest event since the Battle of the Marne. It meant that German imperialism was to be vanquished.

America had taken her place definitively on the side of democracy and liberty, which she valued more than prosperity and peace. She was going to fight because she did not intend to become German.

Already, before this, the idealism of Americans had begun to be felt among the Allies. The gallant conduct on the battlefield of the vanguard of volunteers, the disinterested generosity of the Ambulance units, the Red Cross workers, the American Fund members for French Wounded, and many others, had revealed the fine American spirit of true brotherly love. Charity, however, was one thing, and the war was quite another.

It was known that the United States had only a small standing army and no regular system of military service. England had not been able to vote conscription until seventeen months after the war began. How was America to recruit soldiers, and what sort of soldiers would they prove, under the baptism of fire? These were the questions the Allies, and even Americans asked.

Within a week after the United States had declared war, France had dispatched to America a Mission which included the Minister of Justice, Mr. Viviani, Maréchal Joffre, Admiral Chocheprat, and the Marquis de Chambrun, followed almost immediately by a French High Commissioner, Mr. André Tardieu, who devoted himself to establishing in Washington a well-organized and harmonious collaboration between the two countries.

The victory of the Marne and France's sufferings were personified for Americans in the presence among them of Joffre. The welcome he received was a national demonstration; it rang out with glory from hearts full to overflowing of compassion and of gratitude.

Congress almost immediately voted conscription. The popular response to this act brought, in a fortnight, over ten million enlistments to the recruiting bureaus. Time and space, no doubt, seemed to rise up as two gigantic obstacles to any very successful military effort on the part of the United States, yet a feeling of moral comfort began to pervade the atmosphere, not only of the fighting forces but of civilians.

Russia had gone to pieces, but America had taken her place in line with the Allies.

So, in June 1917, when General Pershing arrived in Paris with the first contingent of the Expeditionary Forces, there were crowds in the streets and about the station to meet him and to acclaim the American soldiers.

The cheers went up like a cry of relief, and when the French saw the smile which answered them, the smile of youth, happy and glad to lend a hand, to lay down as many lives as need be, then the welcome became more personal, a note of instinctive sympathy sounded in the greeting.

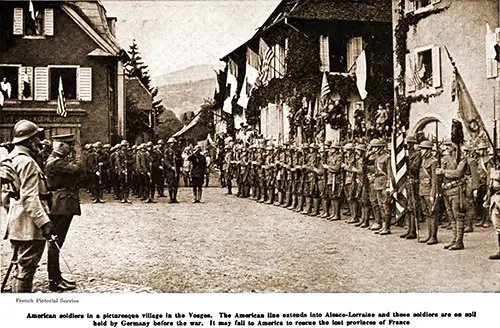

American Soldiers in a Picturesque Village in the Vosges. The American Line Extends into Alsace-Lorraine and These Soldiers Are on Soil Held by German before the War. It May Fall to America to Rescue the Lost Province of France. The Story of the Great War, Volume 14, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18031eb420

From sympathy, the feeling grew to one of respect on the day when General Pershing, standing over the grave of the French General who, in 1776, had helped the United States win her freedom, echoed the lasting gratitude of the American people and pledged the future, in these few words: "Lafayette, here are here!"

That day the four walls of the Invalides resounded to the strains of an American military band. Joffre stood beside Pershing in the courtyard of the historic building. Poincaré was there, and the descendants of Rochambeau and of Lafayette. Flanked by the poilus, tried in battle, alert and resolute, the American soldiers of this first division marched out to meet their fate.

This time it was love that greeted them on their way; women and girls broke up the ranks more than once to embrace these soldiers. From the windows under which they passed; roses were showered down upon them. When they reached the Hotel de Ville, they looked like a moving garden with flowers in their belts, in their hats, in their rifles' barrels.

More appealing still was the spontaneous enthusiasm of the children. The first column of American soldiers as it swayed along at a brisk marching pace, was accompanied by a procession of little people, the lonely little people of France who had seen their fathers, their brothers go out to battle, never to return, and who now clung to the hands of these strong youths from over the seas, with touching confidence.

These were the men they had watched in the "cinemas," they had read about them in books on the Far West; their presence was a dream come true. That first day the children seemed to be leading the American soldiers, showing them to Paris, with pride, as if to say: "They've come, you see. They are our friends. Now we are safe."

One little girl asked if she would sell her American flag, even when offered as large a price as three dollars, stoutly refused. "It is not the flag I cannot sell," she said, "it is my heart."

Nor were their hopes too high. As the Americans increased in numbers and spread out in every direction, waiting to fight, their kindness and generosity became generally known. Speaking of Tours, where many of the troops were quartered, one little, old French woman said: "We have no more poor in our town. The children and the old people are always with the Americans now, and they are all laughing together."

Another day, in a more remote part of the country, a farm goes up in flames. Immediately, the Americans organize an amateur brigade, and when the fire is put out, they pass around the hat and take up a collection of one hundred and fifty dollars to help pay for damages.

"We were so choked," the farmer said, "that we could not even speak."

So the Americans, training for war, went about doing kind deeds. Then, at last, came the call to fight.

The Service of Supplies

The greatest deference and gratitude are due to General Pershing for his far-sighted judgment in planning at once an organization sufficiently vast to accommodate the army, which his military genius realized would be needed to “turn the scale in favor of the Allies.”

The task of preparation to be accomplished was formidable. In the opinion of the Commander-in-Chief, the “immensity of the problem could hardly be overestimated.” Three thousand miles of sea stretched between the most easterly ports of the United States and the most westerly harbors of France.

The best of these, in the north, were crowded by the shipping and supplies of the British Armies. Further down the coast, Saint-Nazaire, Bordeaux, Nantes, La Pallice, while comparatively free, had not sufficient facilities for handling the quantities of material and caring for the numbers of men to be brought across the Atlantic.

Working against all manner of difficulties, in a country which, for over three years, had been devastated by war, the S. O. S. and Engineer contingents built docks, by the mile, they constructed buildings which, if strung out, end to end, would cover a distance of 452 miles; they set up 1,055 locomotives and 14,302 cars sent from the United States, and, for the French, they mended 1,423 locomotives and 45,993 cars.

They laid 1,475 miles of railway and stretched through the air 125,000 miles of telegraph and telephone wire. They handled 129,143,188 objects of clothing; they provided bakeries, which averaged an output of almost two million pounds of bread a day.

When the armistice was signed, the Transportation Service was operating in thirty ports. On the wharves that seemed to have sprung up in a night under American supervision, over five million tons of material had been unloaded.

The record was broken by 135 men of the first company of Railway Engineers to arrive in France. They laid 2.69 miles of narrow gauge railway in about 7 hours. This meant handling 105 tons of steel rails, 1,830 pairs of plates, 7,100 ties, 8 kegs of bolts, 37 kegs of spikes, a total of 230 tons in 433 minutes.

The German Imperial Government had believed it impossible that America could raise an army, equip it and transport it across an ocean beset with submarines which, during the very month when the United States declared war, had sunk 872,300 tons of allied and neutral vessels.

Between June 1917 and November 1918, over two million soldiers crossed the Atlantic. Owing to the convoying of ships, proposed by President Wilson, who, from the first, had proclaimed that America was ready to give her last cent and her last drop of blood, not one life was lost through aggression by the enemy.

America had accomplished the most gigantic industrial triumph in history: she had dumbfounded the Germans who, throughout the world, were celebrated for their system of organization.

All this effort was made so quietly that no one really knew what the Yankees were about, and yet, now that the war is won, the vast accumulation of war material has lost its significance; what endures is the spirit in which the Americans worked. Their ingenuity in saving time and overcoming all obstacles will remain an example of what can be accomplished when the men of g free democracy labor together in fraternal unity for a common cause.

French Assistance

No less quiet and effective was the manner in which the French Government furthered the efforts of the Americans in procuring supplies. Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes, General Purchasing Agent, in his report, has given the following account of French collaboration:

"The demands of the A. E. F. for material in France were tremendous and insistent. Approximately one half of the entire material and supplies used from the beginning to the date of the armistice, to wit about seven million tons, were secured in France."

"The thanks of our nation are due to the members of the French Government. Not only did they assist in every way in protecting the entire purchasing processes of the A. E. F. from exorbitant prices, but they were invaluable in their efforts to expedite the furnishing of supplies from the French Government and to uncover new sources of supply in the open market."

"Whether in the early days we were seeking metal and timber for primary construction, or whether in the later days, in the Saint-Mihiel and the Argonne-Meuse battles we were crying out for horses to take our artillery into action, or for camions to transport our troops, these men of the Haut Commissariat, with an energy and devotion which knew no limit, found in some way, the means to assist us and to enable us to surmount acute crises."

The proof of this cooperation lies in the fact that when the armistice was signed, all of the 75 m/m guns, all of the 155 m/m howitzers together with 65,000,000 shells which had been fired from them, 57% of the long-range guns and 81% of the airplanes in use by the A. E. F. had been supplied by the French.

It had been estimated that the American Army would need 15,000,000 tons of material. Only 9,000,000 tons were actually sent from the United States; the other 2/5 were procured in France.

General Dawes concludes his report with this tribute to the courage which prevailed behind the lines:

"France herself was largely stripped of military supplies. Thus almost every cession to the American Army meant a curtailment acutely felt by some portion of the French people and their brave army. The efforts of the French cooperation remind us that it was not upon the battlefield alone that Frenchmen and Americans were brothers in a common effort."

B. Van Vorst "To The Homeward Bound Americans," University of Virginia, 1918. Note: Pamphlet included in "European War 1917-1818 Pamphlets, Vol. 67.