Foreign Immigration to The United States

Introduction

The article "Foreign Immigration to the U.S. - 1880" provides a detailed analysis of the trends, patterns, and impacts of immigration to the United States during the late 19th century. The article focuses on the year 1880, a period marked by a significant influx of immigrants from various parts of Europe, particularly Southern and Eastern Europe. It explores the factors driving immigration, the demographic characteristics of the immigrants, and the social and economic implications of this large-scale movement of people to the United States.

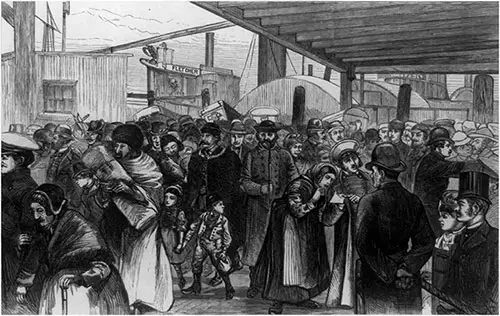

Immigrants Landing at Castle Garden. Drawn by A. B. Shults. Harper's Weekly, 29 May 1880. | GGA Image ID # 1482c22ab1

In busy New York, perhaps the busiest spot during the spring months of 1880 was the Rotunda of Castle Garden. It is a polyglot exchange, the meeting place of the tribes of the sons of men.

Here, a vibrant tapestry of cultures unfolds, each one represented in its unique attire, from the Hungarian's white sheepskin jacket to the Hollander's thick woolen wraps.

Grouped in every possible attitude— some, exhausted by a long voyage, sleeping on the floor, with such chance head-roots as can be found, some cooking, some smoking, some sitting and looking out on what they can see of the New World with wondering eyes—they are n study for an artist.

The diligent servants and officers of the Commissioners of Emigration are ever-vigilant, guiding the newcomers and facilitating their journey to their destinations, be it the nearby states or the distant West. They have efficiently handled as many as four thousand arrivals in a single day.

The volume of immigration to the United States in 1880 promises to be enormous. In 1879, the number of alien arrivals at the port of New York was 179,589; in 1878, 129,866; and in 1877, 109,055. In the first four months of 1880, the number of arrivals reached 81,262, or nearly half of the total of 1879.

In April of this year, more foreigners landed at our port than were ever known to arrive in one month. Of the countries represented, Germany stands first, followed by Ireland, England, and Sweden. Adding England, Scotland, and Ireland together, the total number of immigrants coming from Great Britain in 1879 was 50,206. In supplying us with population, our mother country leads the rest of the world.

Political economists reckon each immigrant's money value to the country. Some have fixed it at $800, some as high as $1200.

When the foreigner who comes to us is usually in his prime and has many years of productive labor before him, the higher estimate does not appear excessive. But this is a very imperfect way of determining the benefit we derive from the inflow of European populations.

Some Old World nations owe a large part of their prosperity to their friendly reception of foreigners driven from their homes. For nearly two centuries, a constant stream of persecuted Protestants poured from the Continent into England, bringing with them arts and manufactures in which they excelled the world over.

Two hundred and fifty thousand of the most moral and industrious of the population of France were exiled by the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In the sixteenth century, upon the arrival of the news of an intended invasion by Alva, one hundred thousand Netherlanders left their homes within a few days.

Historians say that "many of the arts and manufactures which had been most distinctively French passed in the eighteenth century to Holland, Germany, or England."

Twenty thousand French Protestants, "attracted to Brandenburg by the liberal encouragement of the Elector at the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, laid the foundation of the prosperity of Berlin and of most of the manufactures of Prussia."

Therefore, to accurately calculate the value of immigration, we must take into account what it adds to our wealth in the establishment of new industries and the strengthening of existing industries. By importing the artisans of Europe, we import the arts of Europe, domesticate them, and find in them sources of enduring prosperity.

It is not easy to ascertain the number of foreigners who arrived in the United States prior to 1819, as no statistics were collected until that year. It is supposed, however, that it did not exceed 250,000. In 1820, the total number was only 8385; in 1854, it reached 427,833.

Immediately before and during the Civil War, immigration dropped dramatically. When peace was restored, however, the volume of immigration increased again, and in 1869, 595,922 foreigners came to the United States.

During the years of our recent panic, immigration almost entirely ceased. From the foundation of our government to 1870, we added to our population from this source 7,803,605 persons; from May 5, 1847, to December 81, 1879, 5,857,025 arrived at the port of New York alone.

Famine, war, oppressive military systems, the desire to own land, the prospect of better wages, and the preference for a free country will bring the ordinary people of Europe to us in such multitudes as have never before been known. No prophet can predict what the end will be.

The increase in transportation facilities must induce many to migrate who would otherwise shrink from the venture. Those now arriving are said to be superior in quality and to average sixty dollars each.

But where do they all go? One answer to the question must be made—not to the South. Excepting Texas, nothing can induce the immigrants to turn their faces toward the Southern States. To the offers of welcome there and cheap land on easy terms, they turn deaf ears.

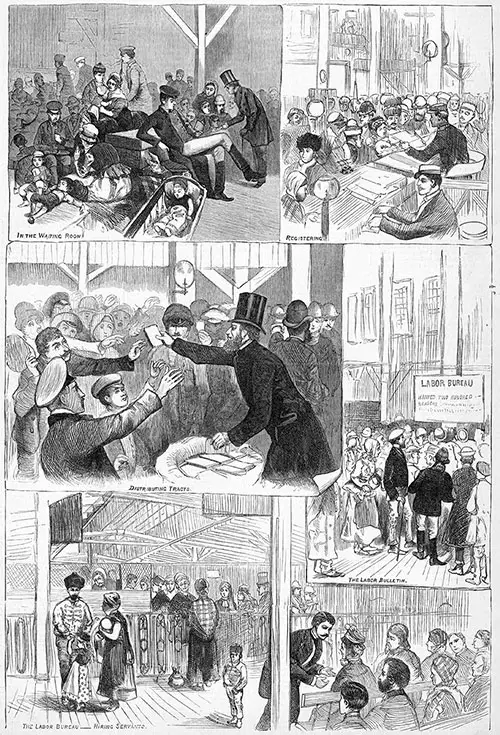

Scenes of Immigrants at Castle Garden. Drawn by A. B. Shults. Harper's Weekly, 29 May 1880. | GGA Image ID # 14b373418d

They are peaceable folk and dread the too-ready knife and revolver. Minnesota absorbs the largest number of strangers, followed by Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, Nebraska, and Kansas. About forty percent remain in the East; some because they are too poor to go farther, others because they meet with good offers of work as artisans, miners, or domestics.

The Commissioners of Emigration, who have been in charge of the landing of immigrants for more than thirty years, have perfected a system that works with mathematical precision. Precision is needed for the six hundred and ninety foreign steamers that bring precious human freight and land to this port each year.

As every New Yorker knows, Castle Garden looks out upon the bay. As soon as a ship arrives, the immigrants' luggage is examined by Custom-house officers and transferred in barges to the landing depot. When the passengers reach the Rotunda, which is spacious enough to shelter several thousand, they are carefully registered.

Every important particular— birthplace, age, point of departure from Europe, occupation, destination—is noted. For some, friends and relatives are in waiting. Loud calls are soon heard, announcing friends' names and the persons waiting.

The Commission officers supervise these meetings to ensure that no fraud is practiced. Packages of money have been sent to some of the newly arrived strangers to pay their fares inland; after proper identification, these are handed over.

Clerks are ready at desks to write letters in any language of Europe, and a telegraph operator with instruments and batteries is nearby to forward dispatches to any part of the continent.

A restaurant under the roof furnishes plain food at moderate prices; cooking stoves with fires enable families to prepare their food if they wish. A missionary, whose ready tongue can change instantly from one language to another, flits to and from giving counsel and distributing religious books.

Sick people are removed to a temporary hospital on the premises, where they receive the best medical attention. Those who are seriously ill are carried by boat to Ward's Island.

Hut, the immigrant, is all this time only on the edge of America. Indeed, he has not yet touched the continent; he has set foot on one of the outlying islands. He can hear the roar of New York outside but dare not trust himself alone to the streets.

The great railway lines have offices inside the Garden, where he can buy his tickets for the far West under the Commissioners' inspection. His baggage is weighed, and a memorandum is given to him explaining the amount of extra weight and the exact charge thereon.

At a broker's desk, he exchanges his foreign money for current American funds. Steam tugs convey the westward bound to the railway stations so that they are not brought into contact with the dense crowds of the city.

Those who will tarry in New York are sent to boarding houses, which are kept under regulations prescribed by the Commissioners of Emigration.

But bow as to work? The abundant work and good pay of America have drawn the foreigner here. How shall he find his way to an employer? The Labor Bureau inside the premises brings the workman and the employer together in a few minutes.

A blackboard in this department announces the wants of the day in English, German, and French. Today, it may announce: "44 Weavers wanted, especially families. Miners wanted. Two hundred farm laborers wanted."

What varieties of labor the motley groups in the Rotunda can supply may be guessed from the 1879 landings of 1,635 professional men at Castle Garden and 21,834 skilled workers.

The professionals were 847 engineers, 17 journalists, 50 physicians, and 28 clergy members. There were only three lawyers, however. Our home legal fraternity need not dread the importation of competitors from abroad at present. The demand for domestic servants is continually beyond the supply.

The immigrants are not by any means an inviting crowd when they arrive. They bear the marks of the rough life of the steerage.

They are the world's poor, but their condition is much above poverty. Despite the begrimed and tumbled look of their persons and household goods, they are full of hopefulness.

The charitable work of the Commissioners of immigration for their benefit is gigantic. All is done without charge to the immigrant. Initially, the expense was met from the payment of head money—not less than one dollar and a half, or more than two dollars and a half, for each passenger—by the ship owners engaged in this trade.

The Supreme Court of the United States, in 1876, declared the law of New York requiring the payment of this sum unconstitutional. Since then, the Legislature of the State has made an annual appropriation of not less than $150,000 for the expenses of the Commission.

This is a temporary expedient only: the National Treasury should bear the charge. The service rendered at the chief ports of entry to immigrants is a service rendered to the whole country. But for this watchful care, many would never find their way to the great fields of West New York, which stands at the principal gate of entrance and superintends the forwarding of the living freight to the sister states.

Indeed, they should not envy the payment of the necessary expense out of our common funds. A bill has been before Congress since January 1877, which places the service now rendered by the State Commissioners under the direction of the Secretary of the Treasury and provides an " Immigrant Fund," from which the cost may be defrayed.

But Congress is busy with President making. We shall have a President in due time —created by the people. Congress would do well to give some thought to the living tide of wealth which, in ever-increasing volume, is pouring into our favored land.

"Foreign Immigration to the United States," in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, New York: Harper & Brothers, Vol. XXIV, No. 1222, 29 May 1880, pp. 341-342.

Foreign Immigration to the U.S. (1880)

An Unmissable Chapter in Immigration History

The article “Foreign Immigration to the U.S. - 1880” provides a vivid and comprehensive exploration of immigration patterns and their profound impact on America during the late 19th century. It focuses on the bustling activity at Castle Garden, the nation’s primary immigrant processing center, and its critical role in managing the influx of diverse immigrant populations. This page offers a wealth of information that is invaluable for teachers, students, genealogists, family historians, and anyone interested in immigration history, illuminating how millions of hopeful newcomers shaped the fabric of American society.

Why Review This Page?

- Rich Educational Insights for Teachers and Students:

- Learn about the socio-economic and cultural impacts of immigration on 19th-century America.

- Study the detailed accounts of Castle Garden's operations and the lives of immigrants passing through its gates.

- An Essential Resource for Genealogists and Family Historians:

- Gain context for tracing family roots, particularly for those descended from immigrants who arrived during this transformative era.

- Discover demographic data and migration trends that could shed light on ancestral journeys.

- Broader Appeal to Immigration Enthusiasts:

- Understand the human stories behind the "living tide of wealth" that immigrants brought to America, from cultural diversity to economic contributions.

- Explore the challenges and triumphs faced by immigrants as they sought better lives.

Key Highlights of the Article

- Castle Garden as a Gateway to America:

- The Rotunda at Castle Garden bustled with activity in 1880, handling as many as 4,000 immigrants daily.

- Immigrants from countries such as Germany, Ireland, and Sweden contributed to the growing diversity of America.

- Immigration Trends and Economic Impacts:

- Between 1879 and 1880, immigration surged, with a record number of arrivals at New York's port.

- Immigrants brought skills, trades, and hope, contributing to the U.S. economy with an estimated value of $800 to $1,200 per person.

- Comprehensive Support System:

- Castle Garden’s operations ensured that immigrants received proper registration, assistance with onward travel, and access to work opportunities through the Labor Bureau.

- Services like money exchanges, affordable food, and medical care underscored the station’s commitment to immigrant welfare.

- Human Stories and Challenges:

- Scenes of joy, hope, and hardship were a daily reality, with immigrants eagerly looking toward their futures in America.

- Barriers such as language, unfamiliarity, and regional biases shaped their early experiences in the New World.

- Policy and Funding Debates:

- The article touches on the financial challenges of operating Castle Garden after a Supreme Court decision ended the immigrant head tax in 1876.

- It advocates for federal funding and oversight of immigrant services, highlighting the national significance of immigration.

Call to Action

This page captures the essence of a pivotal moment in American immigration history, providing detailed narratives, statistics, and cultural insights. It is an essential resource for understanding how immigrants shaped America and how Castle Garden served as both a gateway and a lifeline for millions. Teachers, students, genealogists, and history enthusiasts are encouraged to explore this page to connect with the stories of the past and appreciate the legacy of immigration in building modern America.