A Day At Castle Garden Immigration Station - 1871

Introduction

The article "A Day in Castle Garden Immigrant Station" from March 1871 provides a vivid depiction of the daily activities and operations at Castle Garden, New York City’s primary immigrant processing station in the 19th century. The article offers a detailed account of the experiences of immigrants as they navigated the various procedures at Castle Garden, from their arrival in the harbor to their processing and eventual departure for their new lives in America. It highlights the challenges faced by immigrants, the roles of officials, and the overall atmosphere of this bustling gateway to the United States.

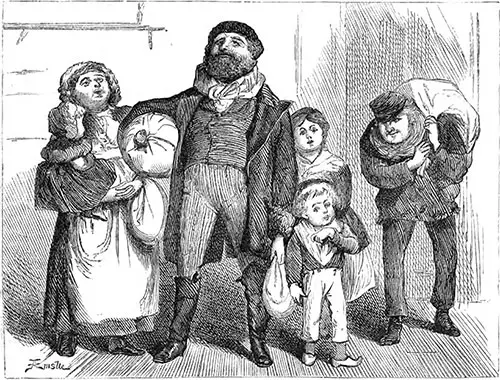

A German Immigrant Family At Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b40de14a

As we made our way down to the Battery in the lower part of Broadway, we encountered groups of newly arrived immigrants. Their faces were aglow with a sense of wonder, as they took in the sights of the city.

Trinity Church and the new magnificent "Equitable Building" on the corner of Cedar Street seemed to be unique objects of attention. In passing, I heard a German woman say of the latter building, "Das muss der Palast sein (This has to be the palace)," an opinion that her companions instantly shared.

A city without a "Palest" of some kind is an impossibility in Germany. At length, we passed through the old iron gate into the Battery grounds. It was a sad sight. What was years ago a blooming garden is now a barren waste on which hardly any sprouting grass is to be seen.

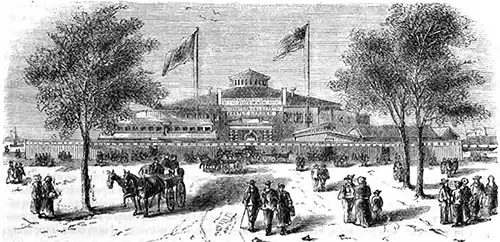

It looks like a large drilling field, with a few trees standing in clusters near the entrance on Broadway. In the background, Castle Garden looms, with its outbuildings, hospitals, and offices—all encircled by a large wooden wall.

Before long, the grounds of the Battery will have assumed their old, almost forgotten, aspect. The landscape is being surveyed and laid out. Gangs of laborers work with pickaxes, shovels, and wheelbarrows to improve the grounds of the Battery. Before another summer, we may hope to see the Battery as it ought to be—one of the most attractive parks in the city.

The location could not be better. There is the fresh sea, with cooling breezes in the hot summer; near opposite lies Governor's Island, and the Jersey shore and the verdant hills of Staten Island are in the distance.

Entering the Grand Castle Garden

Battery and Castle Garden, New York City, circa 1892. Detroit Publishing Company # 7607. Library of Congress # 2016816901. | GGA Image ID # 14b51660a7

Here, the groups of immigrants became more frequent. As we approached the entrance to Castle Garden, we found it almost impossible to make our way through. The passage was blocked up with vehicles, peddlers of cheap cigars, apple stands, and runners from the different boarding houses and intelligence offices that abound in the neighborhood.

Despite the overwhelming scene, we managed to push through, navigating our way through the outpouring stream of new arrivals and the deafening shouts of 'D'ye want a conveyance?' "Hotel Stadt Hamburg!" " Zum goldenen Adler! 'Hotel Stadt Hamburg!' 'Zum goldenen Adler! (To the golden Eagle)' 'This way, gents, this way !' The intensity of the situation was palpable.

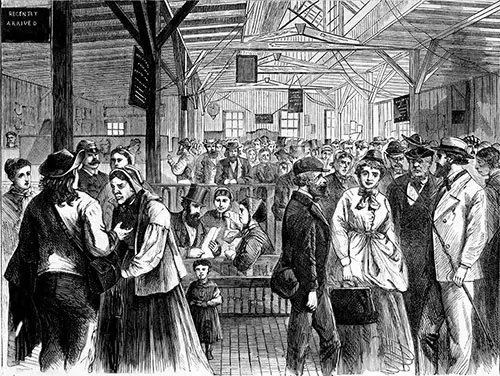

We presented our passports to the officer on guard at the entrance and were admitted. They ushered us into the yard of Castle Garden amidst a crowd of passengers, children, and baggage of all kinds. The different offices connected with the Garden opened into this yard. We entered the main building, which a sign over the large doorway announces as " Castle Garden" proper.

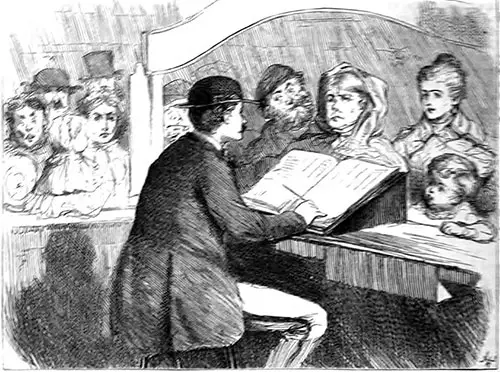

A Clerk at Castle Garden Registers the Name of Incoming Immigrants. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b41ae410

Indeed, it looks like a "castle," but the "garden" is less observable. Open port-holes stare us in the face as we approach but excite no alarm. In the good old times, when this pile was built for a castle, it must have answered its purpose pretty well; the walls are at least fully six feet thick and made of massive square blocks of brownstone, tightly cemented.

The old nail-studded fort gates are there yet, but they are never closed now, a lighter and smaller gate having been made to supersede them.

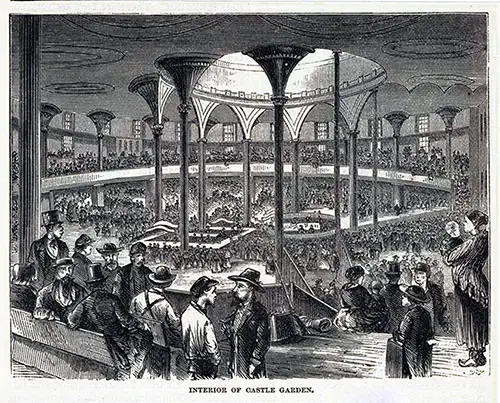

Passing through the gateway, we have a roomy and clean washroom for females on the left side. On the opposite side, a washroom for males is plentifully supplied with soap, water, and ample clean towels on rollers for all immigrants' free and unlimited use. From these rooms, we emerge into the rotunda—the main feature of Castle Garden.

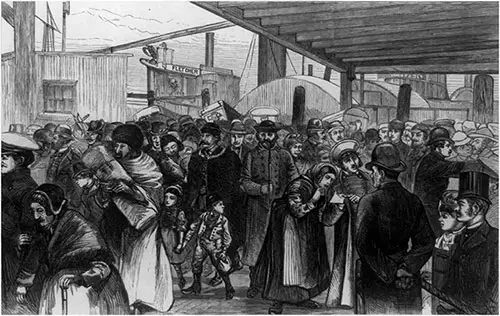

Landing of Immigrant Steerage Passengers

Immigrants Landing at Castle Garden. Drawn by A. B. Shults. Harper's Weekly, 29 May 1880. | GGA Image ID # 1482c22ab1

The steamer Holland from Liverpool had just arrived, and the steerage passengers were being landed. It was a motley, unusual throng. Slowly, the newcomers passed the two immigration officers whose duty is to register every immigrant's name, birthplace, and destination in large folios—work that is often somewhat more difficult than it would first appear to be.

First, the officer in charge must be able to speak and understand nearly every language. This, however, can be learned and mastered. But then arises a second difficulty—the remarkable lack of intelligence and the regularly recurring misapprehension shown by some of the passengers. These latter instances are very numerous, and dealing with them requires a great deal of patience.

Some of the immigrants' responses are exceedingly comical. For instance, a young fellow in corduroy knee-breeches and nailed shoes was asked if he was alone in my presence.

"No, Sir," he said boldly, and upon being asked who was with him, he answered, "Sure, my box."' Another wanted to register two gamecocks he had brought with him from Tipperary.

"Sure, I paid for their passage," he said. Still another—an older woman—was asked her name, and she said it was on her box. "If we wanted to know, sure, we could go and see." Upon being asked by a bystander how her box would be found, her answer was, "Ah, be jabbers, and isn't my name painted plainly on it?" It was with difficulty that her name was finally ascertained.

Some do not understand a word of English and can only speak Irish, but these are few and are nearly always older adults.

Booker - Railway Association Clerk

Onward, the immigrants passed one by one, in a single file, until a few steps farther down, they came to the desk of the so-called "booker," a clerk of the Railway Association. His duty was to ascertain the destination of each passenger. He would then furnish a printed slip that stated the number of tickets wanted along with their cost.

After receiving this, the passenger is passed over to the railway counter, where he may purchase his ticket. He can then decide which railroad to patronize and whether to take the first-class or immigrant train.

This arrangement is very productive. If the immigrant buys his ticket here, he will only be charged the price and get the total value for his money if he pays with foreign currency. It is too often the case that passengers buying their tickets outside offices are shamefully swindled; the daily press exhibits numerous instances of this.

Furnishing an immigrant with the proper and correct ticket can be challenging. This may be conjectured from one example. A Swedish passenger desired to go to Farmington. Still, as there are at least twenty-one cities and Tillages of that name in the United States, this address could have been more satisfactory. He was asked by the Danish clerk attached to the Railway Bureau what state that particular Farmington was in, but he needed to learn this.

He had no further details of an address other than Farmington, US. It was probably out West, as nearly all the Swedes were far travelers, with Illinois or Iowa being consequently suggested, but he did not know.

Finally, he remembered something about "Da," or " Dada," or "Dakota." It was found to be "Farmington, Dakota County, Minnesota," a fact proved correct by letters he later produced from his trunk. He received a ticket accordingly and went on his way, rejoicing the same afternoon.

Exterior View of Castle Garden from the Battery. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b44093f9

Instances where passengers know only the name of the city to which they are destined, but not those of county and State frequently occur, give a great deal of trouble to the railway employees.

Ascertaining the right place is of the utmost importance, and sometimes, considerable skill and experience are required to avoid mistakes. In some instances, it becomes wholly impossible to discover the destination and forward the passenger.

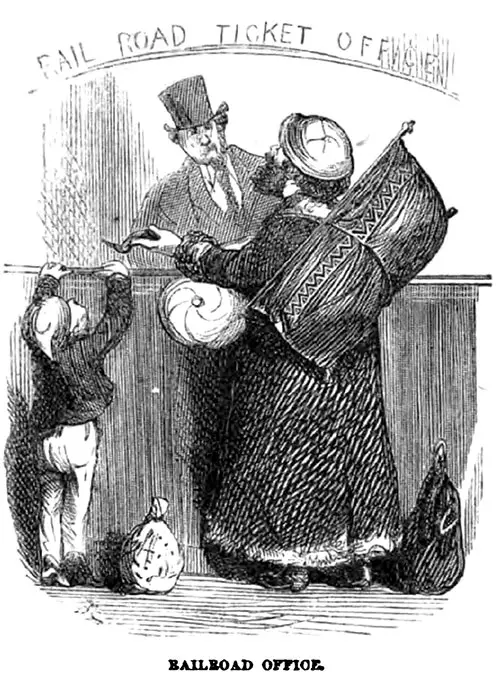

The Railroad Ticket Office at Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b44490c8

The Railway Agency is under the strict control of the Commissioners of Emigration. It is held responsible for the purchaser of a ticket for any mistake that may occur. Few outside ticket offices, not so controlled, care about exercising the same care and vigilance in forwarding a passenger; they only want his ticket purchase and departure out of the way.

The immigrant, often facing such challenges, demonstrates remarkable adaptability. He may consider himself lucky if he arrives at his destination, especially if it's a significant city like Chicago where mistakes are less likely. And even if he finds himself a couple hundred miles off course, he has paid his money and must be content despite any desire to voice his concerns.

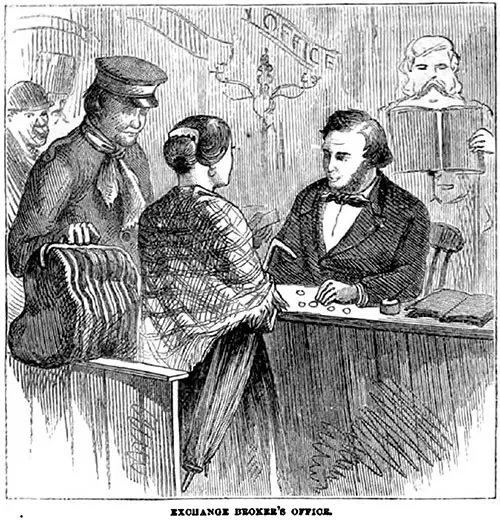

Foreign Exchange Brokers

Directly opposite the railway counter are the exchange brokers' desks, which are currently occupied by four firms, each working in its own interest. A blackboard conspicuously displayed announces the current rates at which foreign and domestic coins are exchanged—at a rate that is but a trifle below the Wall Street quotation.

Whenever a change occurs in the street, it is instantly reported to the brokers in the Garden, and the rate on the blackboard is altered accordingly. And this, too, puzzles our transatlantic friends. An Englishman changes a sovereign, for which he receives $5.70, according to the then-present rate. A moment later, gold goes down one percent or one and a half on Wall Street; it is instantly recorded at the Garden, and the prices are altered accordingly.

Our friend comes along again with some more sovereigns to change for himself and his comrades, but now he only receives $5.65 for his gold. "Ay, Sir, you have made a mistake," he says. The broker's clerk says he has not and tries to explain, but it is no use. Less than two minutes ago, he got $5.70 for his sovereign, and now he gets five cents less!

That surpasses his comprehension. "No, no," says he, shaking his head incredulously, "gold is gold. This 'ere is good British money; no change in that; that stands to reason." He is offered his sovereigns back if he chooses but lets it pass, scratching his head and saying, "Blast the durned paper money that one can't make neither head nor tail out of!"

Of course, often, the opposite happens, and the price of gold increases in the interim between a customer changing his coin. Then he gets a higher price for the last lot but never complains.

Currency Exchange Broker's Office at Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b4530efa

All kinds of money are exchanged here, and often in considerable quantities. They informed me that one individual often changed as many as two to three hundred sovereigns and one to two thousand Prussian thalers into paper money.

While I was there, a passenger exchanged a bag of sovereigns containing at least fifty pieces for the full value in United States currency with a memorandum of the transaction signed by the broker.

This Currency Exchange Broker's Office at Castle Garden is under strict control and surveillance by the Commissioners, who look out for the interests of the immigrants.

Sovereigns and Prussian thalers form the bulk of exchange. Still, other coins of nearly all countries and denominations are also exchanged daily. American gold is very frequently brought over and, if not changed at the Garden, often leaves the unsuspecting immigrant's pocket at par.

Twenty-dollar pieces, eagles, and half-eagles are the denominations most used. Still, many bring over small one-dollar gold pieces. About one in every four or five are perforated with a hole as if used for a charm.

Interior View of Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b46c8b0e

This is a ploy frequently resorted to on the other side; the pieces are drilled, which, on average, causes them to lose about fifteen to twenty percent of their value. But they are sold at full price and often more to the emigrants in Liverpool. The fine dust thus drilled out makes a handsome extra profit for the unscrupulous broker.

Others bring bags full of American silver of small denominations, which they have also obtained in Liverpool, where it is imported at a considerable discount from Canada.

Strangely, spurious coin or paper is seldom found in the possession of the immigrants. However, there would be a broad and comparatively safe field for imposing these upon emigrants before departure from Europe.

Passengers via Bremen very often bring with them American greenbacks, having changed their money prior to their departure. The currency is almost always genuine. Sometimes, a corner is missing, or a bill is otherwise somewhat mutilated.

The Mecklenburger Farmer at Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b4713d1f

A Mecklenburg farmer arrived some time ago and carried a considerable sum of money in greenbacks on his person. To keep it safe, he sewed it into the lining of his shirt, which he wore during the whole voyage.

When he opened his package, he found that two fifty-dollar bills had become stuck together. This was caused by his body's sweat and some adherent matter, probably sticking to the paper. It was impossible to detach them. They stuck together as one bill as nicely as if an artist had glued them together.

Loud were his lamentations and great his distress. He tried to peel them carefully asunder with his thumb-nail but only tore the paper. He cried when somebody advised him to give the refractory bills a cold-water bath.

He caught the idea and did so, and lo! the bills came apart as nicely as two sheets of mica, and his one fifty-dollar bill was suitable for a hundred dollars. Great now was his joy, and he was shortly after seen treating at least a score of his shipmates to schnapps and lager.

One poor fellow who came over to Holland, a Frenchman, brought with him a Parisian bank note for fifty francs—all the money he had. Under other circumstances, the note would have been exchanged at the Garden at par value. Unfortunately, owing to the uncertain value of French paper money caused by the war, it could not be redeemed there.

He could not possibly understand how a note for fifty francs from the Bank of France could not be equal to the same amount in bright silver or gold. It was at par at home when he left, and his faith in the Bank of la Belle France was unshaken. He refused to change it at a discount and left, doubting and disgusted, to be fleeced by some outside sharper.

The war also depreciated Prussian paper money. Formerly, the paper tinder stood a trifle above par (probably one-quarter percent) for the facility in carrying, but now it stands about two and a half percent below. This puzzles German immigrants.

The thaler is in their country a thaler, whether silver or paper and if the latter even a little more; and why should it be otherwise here? "Das Kann ich nicht verstehen (I can not understand that)," they say. However, as a class, they are easily satisfied that it is correct and accept their fate without grumbling.

Most of them bring "harte" (silver) thalers, but it is generally in large amounts when they do. It is not seldom that one paterfamilias brings with him a chest full of bright thalers that it takes two or more men to carry.

With their money exchanged, they purchase their railway tickets. Then they head West, buy lands, settle down, and form one of the most desirable classes of citizens of this great republic.

Immigrants From Many Countries

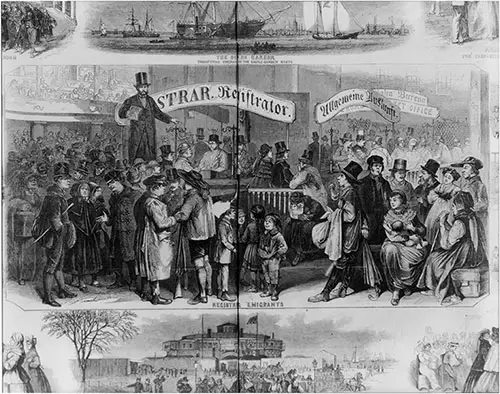

Registering Emigrants at Castle Garden. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 20 January 1866. | GGA Image ID # 14b6092d2a

The German immigrants seem to cause the most minor trouble in the Garden. They are willing, obey instructions, and try to help each other.

Suppose one of their parties is short a couple of dollars to purchase a railway ticket. In that case, he can often raise the shortage with the assistance and cooperation of a few compatriots.

The Irish could be more troublesome with their frequent and repeated questions. Still, the most annoying and patience-exhausting fellow creatures are undoubtedly the Swedes.

They are an excellent class of people and form outstanding and most desirable citizens, but they cause a great deal of trouble on their arrival. First, the smell of a compound of leather, salt herring, onions, and sweat is challenging to describe but most apparent to the senses. Then, they speak a language that no native Scandinavian can understand.

They are, through their very nature, suspecting and doubting. This trait is made more pronounced by people in the old country who try to guard them against Castle Garden and its provisions as if it were some terrible institution.

Therefore, they are indeed challenging to deal with. The Swedes shun questions and often refuse to give explanations. But after some time, when they learn to know the country and the character of its inhabitants better, they find out that we are not as bad as we are painted. They assimilate with us and become hardy laborers and honest citizens.

Swedes are nearly all travelers to the Midwest, finding their way to Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota. There, they find a climate not unlike their own and soon settle down as thrifty farmers.

In recent years, the Swedes have formed a very conspicuous part of our annual immigration. Not less than 23,453 arrived during 1869, nearly 10,000 more than arrived in 1868, and approximately 20,000 more than the arrivals during 1867. Of these, it is safe to say that ninety percent went out West as agriculturists.

According to the annual report for the year 1869, published by the Board of Commissioners of Emigration, the total arrival of immigrants landed at Castle Garden from foreign ports during 1869 was as follows:

- Germany, 99,605

- Ireland, 66,204

- England, 41,090

All other countries together (including Swedes, Norwegians, Danes, etc.), 52,090

... thus making a total for 1869 of 258,989 souls.

The arrivals from France are comparatively few, with only 2,870 arriving that year. Among the other nationalities are five from Greece, five from the Celestial Empire (whether shoemakers or not, I do not know), twenty-three from Africa, four from Australia, two from Armenia, seven from Turkey, and two from Jerusalem—the latter probably the Wandering Jew and his brother.

Immigrants Reading Letters from Friends. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b4767b2e

With his money changed and railway ticket purchased, if he is a traveler, he proceeds to have his 'baggage weighed and checked through to his point of destination.

But before he does that, he has probably received a letter addressed to him at the Garden, which has been awaiting him there. Perhaps he desires to announce by letter his safe arrival in New York to friends far away. If so, he will find a clerk at his proper desk, ready to write for him and forward his letter free of charge.

If a letter is awaiting him, his name is called out loudly after the landing. First, registrations are performed, and before he is permitted to leave the premises, he is furnished with a card announcing that a letter is awaiting him. This card enables him to receive the letter upon presentation of the card at the letter desk.

If there is money for him, it is paid to him promptly, or a ticket is purchased for part of it if the sender so desires. If he wishes to telegraph, there is a telegraph office at Castle Garden and the operator at his post. After accomplishing these tasks, if he feels faint and hungry, there is a restaurant in the corner. All these functions are under one roof and one management.

To be sure, the fare in the restaurant, or bread stand, is of the most everyday kind, consisting chiefly of white and brown bread, pies, coffee, milk, and sausages. Still, it is good, substantial, cheap, and tastes well after the hard-tack and salt mess they had on board the ship.

Before he starts for his new Western home, the washroom is already mentioned, where cold water, stone troughs, and fresh towels invite him to a bath and a change of linen.

The Landing of Immigrants

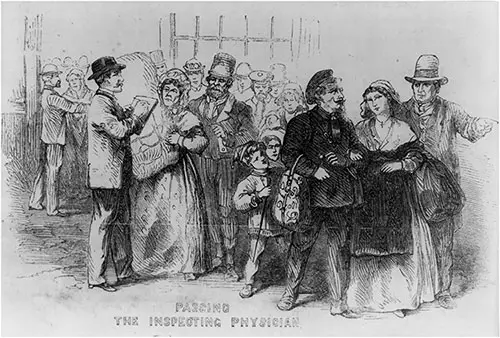

Passing the Inspecting Physician at Castle Garden. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 20 January 1866. | GGA Image ID # 14b5b595ca

Once this has been done, he prepares to start. The baggage room and scales are located outside on the dock where the passengers are landed. Here, his boxes and "kistes" are weighed and checked according to his ticket. There are also several small wooden structures containing offices for the Customs House officers and police detailed for service at the Garden.

One lady inspector's duty is to examine the dresses of suspicious-looking female immigrants. Often, she makes a plentiful harvest of laces, pieces of velvet or silk, jewelry, or the like that is concealed upon the person in the most ingenious manner.

Police stand guard at Castle Garden's entrances. Additionally, they are stationed on the steamship during passengers' transfers to the barge that takes them to Castle Garden.

Two barges are attached to the landing department, weighing about 80 or 160 tons. The passengers and their luggage are transferred from the steamer and brought ashore by the assistance of a tugboat. It is curious to see such a heterogeneous crowd land.

The Swedes are distinguished by their tanned leather breeches, waistcoats, and peculiar before-mentioned exhalations. You must catch the Irishman with his napless hat, worn coat, and corduroy trousers; the Englishman you know by his Scotch cap, clay pipe, and paper collar.

The Teuton is immediately identifiable by his long-skirted dark blue woolen coat, high-necked brass-buttoned vest, flat military cap, or gray beaver. Indeed, one of the immigration officers told me that he could tell exactly what part of Germany each individual came from just from the clothing they wore.

Then there are the Bohemians (the genuine ones), with their many-colored scarfs and glaring jackets for the women and natty military caps for almost all the men. The French in their blue linen blouses. And, finally, the Norwegians in their curious national dress. Their Folk Costume consists of a gray woolen stiff-necked jacket covering only about one-third of their back. At the same time, the front slopes down to a greater length and is profusely ornamented with large silver buttons set close together, which appear to overlap each other.

Their dark woolen breeches reach nearly up to their necks behind, and only a small strip of jacket with an enormous stiff collar is between.

You can not correctly say "a Norwegian in a pair of breeches" but must say "a pair of breeches with a Norwegian in them." This, of course, only applies to the farmers from the interior parts of the country, the "Dalkuller" and "Troensere," etc.

One of Castle Garden's most essential bureaus is Ward's Island and its medicinal departments. These offices are in a long wooden building on the right of one story. As you enter the Garden from the Battery, these departments have done a great deal of good and allayed terrible sufferings and suspense.

Ward's Island - Immigrant Hospital

Ward's Island is a small island in the East River, about five miles from the heart of New York City. The Board of Commissioners is on Ward's Island, a densely populated immigrant refuge and hospital.

Here, immigrants without means are kept and taken care of at the Board's expense until assistance arrives from their friends in the form of money or tickets or they find work as laborers.

I shall not go into the details of this particular institution here, as these alone would fill up and justify an exclusive description. But I will merely remark that the buildings are large and excellent and that their inmates enjoy all the care and comforts suited to their circumstances.

In 1869, 11,471 sick or destitute immigrants were admitted to the Island, 439 children were born, and 11,356 passengers were discharged during the same period. On December 31, 1869, 1,951 souls remained in the institution.

On entering the Ward's Island department, we pass through the areas set aside for the reception of immigrants by their friends. This is a large, well-ventilated room with wooden benches for the visitors' accommodation. A large blackboard shows the names of the steamers or ships that are reported "up," whose passengers are being or will be landing.

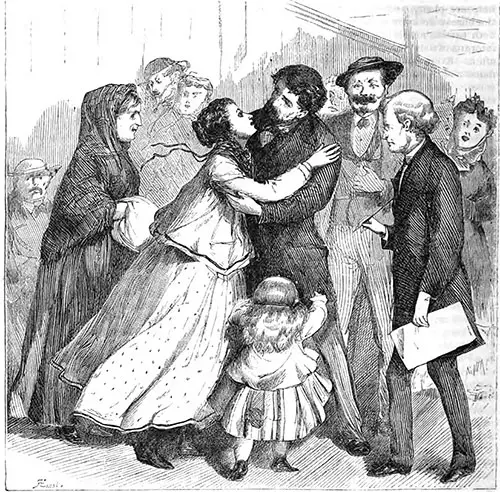

Friends and Family Members Are Meeting at Castle Garden. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b47e5589

If a friend is arriving in the steerage of SS City of Paris, read the list of arrivals in your paper every morning about the time the steamer is due. When you find she has arrived, you go to Castle Garden to this office, which has a separate entrance from the Battery. There, you give the clerk in charge the name of the passenger you are expecting.

This will be called out inside the rotunda, and if she has been on board, she will be sent over to you when there are any quantity of questions to ask and answers to make. It certainly is fascinating to witness these meetings, as I did.

When the name of a comely Irish girl is called out, she enters blushing and, in the next moment, in the arms of her faithful sweetheart, who left his home in Ireland three years ago. He has now sent for her to make her his bride.

There is kissing, crying, squeezing, and applause from the bystanders, who, for the moment, forget that in a few minutes, they will probably do the same sort of thing. That is a new version of "Pat Malloy," and, I think, the right one.

Father and son, sister, and brother, meet here in fond embraces, with tears of joy, after years of absence. What shaking hands, assurances of love, and inquiries for those dear to the heart, still thousands of miles away!

The Labor Exchange - Where Immigrants Find Work

The Labor Exchange -- Interior View of the Office at Castle Garden, New York. Sketched by Stanley Fox. Harper's Weekly, 15 August 1868. | GGA Image ID # 14805c4868

Opposite this building is the Labor Exchange, with a separate entrance from the Battery. Immigrants and whoever else wants work can apply here and will generally succeed in finding an employer.

Farmhands and mechanics have the best chance, and there are always a number of them, mostly raw hands. Miners from Wales and other places are quite a specialty and are always in demand. Weavers also seem to find ready employment. Next come laborers on railroads, farmhands, and gardeners.

There is but a reduced chance for office clerks and other nondescripts. Servant girls form a significant proportion of the work-seekers. They may always be seen sitting there like hens on a perch, scrutinizing and criticizing the employers who apply at the office for help.

It is a mistake, however, to suppose that these girls are always green. Most of them were immigrants once, but that may have been five or perhaps ten years ago. As the office is open to all, it is liberally patronized. There are plenty of applicants for help, and the officers in charge of the bureau do everything in their power to suit both parties and bring about a bargain.

The interests of those soliciting work are well looked after. Everyone applying for help must give their name and residence and furnish references. The wages are agreed upon and entered into a book. In short, everything is done to guard against the admission of doubtful parties.

German girls who recently landed are significantly in demand at this establishment, and I was told there are ten applications for them deep on the books. Still, they are very rarely to be found. German girls seldom come to this country alone; they are nearly always in company with their father, mother, and the whole family and go with them to the Western States.

If a stray one happens to stop in New York, she is picked up immediately, and her services secured at high wages. The wages girls obtain for work from this exchange vary from nine to fourteen dollars per month, sometimes higher. The pay is according to worth and specialty of work; cooks and chambermaids receive the highest compensation.

By far, the more significant portion of the applicants is Irish. Many of them are old "rounders," who take a job for perhaps a month and then leave it without the slightest notice.

Danish and Swedish girls are also in high demand but need help to obtain. Like the German girls, they seldom leave the family where they are employed as long as they are paid decently and well treated.

The female department of the Labor Exchange is managed by a lady who tries to accommodate both employer and employee. No charge is made to or received from either party.

This makes the establishment extensively patronized, as will also be proved by the following statistics: In 1,559 situations were obtained for no less than 11,073 house servants, 438 cooks, laundresses, etc.; and, of the male branch, for 17,250 agricultural and unskilled laborers, and 5594 mechanics of various classes. This is a fair exhibit and helps to illustrate the vastness of the operations conducted at Castle Garden.

The City Express Office

We proceed to the City Express office from the Labor Exchange, where a busy scene awaits us. Wagons are being loaded, and heavy boxes and trunks are rolled on trucks. Along with the smooth asphalt flooring, bundles, beds, and baskets are scattered, with confusion and noise everywhere.

Every immigrant can carry their luggage by express to any city area for a small fee. Only some fail to avail themselves of this opportunity. Consequently, there is a steady asking for and delivery of addresses in all the world's languages.

The Boarding House Keepers

An essential feature of Castle Garden is the attendance of boarding-house keepers. A certain number are admitted into the Garden, where they ply their vocation after passengers land and have passed the registering and railway officials, etc.

They are all provided with cards stating, in several languages, the name of their house and the prices charged. These vary from $1 to $1.60 per day for Board and lodging or $6 to $9 per week, all payable in currency, which is distinctly stated on the card.

Their houses are primarily in Greenwich and Washington streets, near Castle Garden. Most of them have very conspicuous and imposing names. Often, they refer to the nationality of the proprietor, such as Intel de Paris, Würtemberger Hof, Zuni Grüdi (Swiss House), Miners' Arms, and the Cork House.

Some have a Masonic title, such as the Square and Compasses. In these, the immigrants can rest for a day or two before their departure for the West. The Board furnished is said to be good and substantial, and complaints of extortion, etc., are seldom made.

Immigrants Beware

It's different for outside houses or those not represented on Castle Garden premises. Here, complaints are frequent and justly so. As in many instances, these establishments are pitfalls for unsuspecting immigrants. He is fleeced of his last dollar and then thrust out into the street, sent to a brickyard, or " shanghaied" on Board some ship for a three-year cruise.

The immigrants are repeatedly warned against these outside dens in Castle Garden, but of course, sometimes they fall prey to their own folly and do not heed these warnings.

The outside labor exchanges or intelligence offices, also located near Castle Garden, are mostly nothing but deceptions. There, a dollar or two is exacted for the promise of procuring a job. Unfortunately, a job is very seldom furnished. When a job is found, it is of the meanest sort and poorest paid for.

On the second floor above the washrooms are the various offices of the Commissioners of Emigration, their meeting rooms, the Treasurer's office, and the office of the General Agent and Superintendent. This gentleman has, for many years, managed and directed the interior workings of this vast establishment to the benefit of hundreds of thousands of immigrants.

The Commissioner is a man steadfast in his duty, with years of experience and a warm heart. He looks out for the welfare of the immigrant. The Board of Commissioners assists the commissioner, which consists of the most experienced and esteemed men of the metropolis, including the Mayors of the cities of New York and Brooklyn.

On the occasion of my visit, I had an excellent opportunity to inspect this establishment in all its details, and I availed myself of this in the fullest measure. I have tried to describe what I saw and hope to have succeeded in imparting to the reader some idea of what Castle Garden really is and how it looks on a busy day.

The War in Europe

The war in Europe has wreaked sad havoc on emigration. German steamships have stopped running, and only a few of this nationality have arrived. It was interesting to note the landing of about a hundred passengers who had arrived on a sailing ship from Bremen.

They were mostly Germans, with a few French and Italians. They had left their homes before the war. They spoke of their astonishment upon hearing the news up to the hour of their arrival, which can better be imagined than described.

The French looked downhearted, and the Germans exulted; the Italians were neutral. A few of the Germans, young, strapping fellows, inquired about the way to the German consul, as they wanted to go home again and fight for "Vaterland."

Their enthusiasm, however, seemed to evaporate after some time, and they took tickets for Kansas. Meanwhile, the French regained their faith in La Belle France and thought it might not be so bad.

Statistics from the Board of Emigration

I can not refrain from adding a few figures from the Board of Emigration's statistics, as this will, better than anything else, show the importance of this establishment and the quantity of business transacted.

In 1869, 2,884 letters were written for immigrants to their friends, to which answers were received at Castle Garden containing $41,615.55. Remittances amounting to $50,549.49 were also collected in anticipation of the arrival of passengers. 5,393 telegraph messages were forwarded, to which 1,351 answers were received. 504 steamers and 209 sailing vessels arrived with passengers during the year.

$10,876.89 was spent to pay the passage of destitute immigrants back to Europe. This included money provided to their friends in the interior out of the Commissioners' funds.

Problems After Leaving Castle Garden

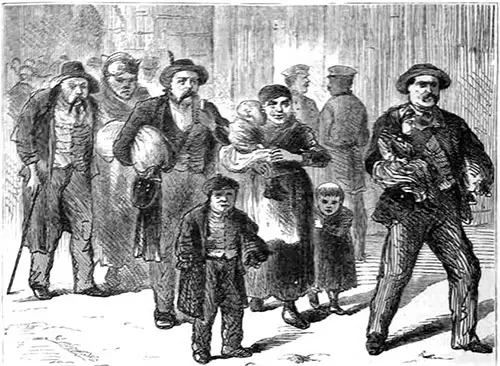

When we left the Garden, we heard the same noises that had greeted us earlier in the morning. We came out among a large party of newly landed immigrants, and the light was but feeble. We were evidently supposed to belong to them.

A fellow grasped my arm and tried in half English, half German, to persuade me to go with him to some obscure " hotel," " das beste in der Stadt! (the best in town)." He discovered his mistake only when we came within the full glare of a gas lamp and let me go, though I had yet to speak a word. A minute later, I saw him carry off some verdant ones with better success.

Immigrant Runner at Castle Garden. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1871. | GGA Image ID # 14b47f5054

It is a standard dodge among these runners to seize a portmanteau or, better yet, a baby belonging to some large family, for the whole crowd will follow.

I encountered such a gang. The wily runner was carrying a massive bag in the left hand and had a yelling baby on the right arm, which he vainly tried to soothe or smother, I do not know which. Behind him came the mother with another baby in her arms and many children clinging to her dresses. After she came "Victor," smoking his Dutch porcelain pipe and carrying some bundles, and finally, "Grossvater" and "Grossmutter" made up the rear.

The lights were shining feebly on the Battery. The lamps are few and far between, and almost total darkness prevails in some places. Behind me were the crowds of immigrants still emerging from Castle Garden, whose dome loomed up splendidly out of a sea of darkness—a beacon for the guidance of immigrants who arrive on our shores.

Louis Bagger, "A Day in Castle Garden," in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, Vol XLII, No. 250 (CCL), March 1871, p. 547-556.

Castle Garden: A Vital Chapter in Immigration History

The Castle Garden Immigration Station, as vividly described in the 1871 article “A Day at Castle Garden,” serves as an indispensable window into the experiences of 19th-century immigrants arriving in America. This bustling hub in New York City was not merely an entry point for millions but also a place where hope, resilience, and adaptation were on full display. For teachers, students, genealogists, family historians, and history enthusiasts, Castle Garden offers invaluable insights into the processes and challenges of immigration during this transformative era.

Why Explore the Castle Garden Story?

- Rich Historical Context

The article captures the daily operations and vibrant atmosphere of Castle Garden, from the rigorous documentation process to the chaotic yet purposeful environment that greeted newcomers. It showcases the personal stories of immigrants navigating language barriers, cultural shocks, and bureaucratic systems. - Educational Value for Teachers and Students

- Teachers: Use this detailed account to bring history lessons to life, exploring themes of immigration, public health, and urban development.

- Students: Gain firsthand insights into the immigrant experience for projects, essays, or discussions on the social and economic impact of migration.

- A Treasure for Genealogists and Family Historians

- Castle Garden’s meticulous records of names, destinations, and personal details are a goldmine for uncovering family histories.

- Anecdotes of specific immigrant groups and their unique challenges offer clues for those tracing ancestry.

- Broad Appeal to History Enthusiasts and Collectors

- The vivid descriptions of immigrant attire, customs, and interactions paint a detailed picture of life in the late 19th century.

- The article’s imagery of Castle Garden as a vibrant, multicultural melting pot enhances its allure for collectors and history buffs.

Key Themes from the Article

- Immigrant Challenges: Tales of mistaken destinations, cultural misunderstandings, and language barriers highlight the resilience of newcomers.

- Processes and Infrastructure: From the registration of names to the issuing of railway tickets and currency exchanges, the article details the logistical efforts behind immigrant integration.

- Cultural Diversity: The descriptions of attire and customs showcase the rich tapestry of ethnicities passing through Castle Garden.

- Labor and Opportunity: The labor exchange underscored the economic contributions of immigrants, connecting them to jobs across the country.

- Public Health Measures: Inspection rooms and vaccination certificates reveal early efforts to safeguard public health.

Why This History Matters Today

- Human Connection: The Castle Garden story reflects the universal journey of hope and adaptation that defines the immigrant experience.

- Relevance: Issues of immigration, cultural integration, and public health remain central to modern discussions, making this historical account particularly timely.

- Legacy: Castle Garden laid the groundwork for Ellis Island and subsequent immigration policies, shaping the American identity.

Call to Action

Whether you’re exploring immigration history, tracing your ancestry, or seeking to enrich your teaching or learning, Castle Garden offers a compelling narrative of perseverance and promise. This detailed account invites you to uncover the stories of the millions who passed through its gates, leaving an indelible mark on America’s past and present.