Atlantic Liners of Today - Recent Records

The Atlantic Liners of Today

With the introduction of the New York and Paris, and the White Star boats, Majestic and Teutonic, additional length with increased speed became the leading factor in the competition.

The success of the new twin-screw ships compelled the Cunard Company to build again, which had for several years, relied upon the Umbria and Etruria. To compete with its rival, it launched the Lucania and Campania, twin ships of 12,950 tons and 30,000 I. H. P., 620 feet long, 65.3 feet beam, and 43 feet depth of hull.

The engines of the Paris indicate twenty one thousand horse power, those of the Teutonic about sixteen thousand. When the Campania and Lucania, with their thirty thousand, began smashing records right and left, the Cunard line was satisfied that its flag was likely to remain supreme upon the seas for some time. But it was doomed to disappointment.

Today there are three ships in commission which at several points excel the crack Cunarders—the Deutschland, of the Hamburg American line, the Oceanic, of the White Star, and the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, of the North German Lloyd.

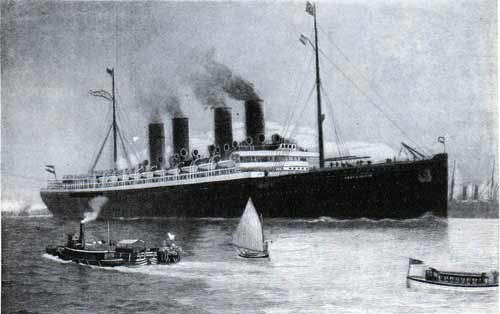

The Hamburg American liner Deutschland, the fastest passenger steamer now afloat- 16,000 tons, 33,000 horsepower, 686 feet long, built at Stettin, 1900.

In speed, both the Deutschland and the Kaiser Wilhelm surpass the Cunard boats; in size, the Oceanic surpasses everything. Over all, the White Star boat measures 704 feet; in speed, she can reel off with clock-like regularity about 20.5 knots an hour, as against the 21.90 knots of the Lucania.

The best hourly average of the Kaiser Wilhelm is 22.6 knots an hour; that of the Deutschland, as has already been said, is no less than 23.36, or nearly a knot an hour better. To the great Hamburg American flier must be given the title of queen of the seas.

The Queen of the Seas

The Deutschland's fastest passage from New York to Plymouth was made last September, her time being five days, seven hours, and thirty eight minutes -- about one fifth of the time taken by the Savannah. During this test of energy and speed, she developed 36,913 horsepower at a daily expenditure of 572 tons of coal.

The size of the huge mechanism that develops such titanic strength and speed may be gauged by the fact that it is forty-five feet from the lower platform in the engine room to the top of the high-pressure cylinders. Moreover, the engines are as ingenious as they are colossal.

They are of the quadruple expansion type, with two high pressure and two low-pressure cylinders. Each high-pressure cylinder is superimposed upon a low-pressure cylinder, where they work in tandem upon the same piston rod and crank.

Steam, at 213 pounds pressure, is led first to the two 361 inch high-pressure cylinders; it is then exhausted into a 731 inch first intermediate cylinder, and then into the two 1081 inch low-pressure cylinders. After this work, it is led to the condenser.

The parts of the machine are of massive proportion. The crankshaft is 59 feet 3 inches long, and weighs a fraction under a hundred tons. Each low-pressure piston weighs seven tons, the piston rod three tons, the connecting rod ten tons, and at full speed, the screws revolve eighty times a minute. The steam that provides activity to this vast leviathan is developed in twelve double and four single boilers, heated by no fewer than a hundred and twelve fires.

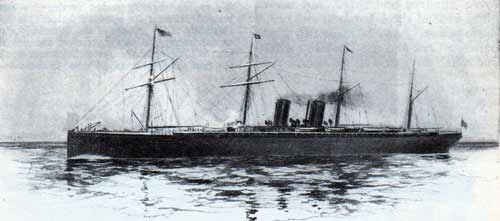

The Guion liner Alaska, the fastest steamer afloat in her day, and the first to cross the Atlantic within a week. She held the record between New York and Queenstown from 1882 to 1884.

In ships of this class, it is hardly necessary to point out that comfort has grown with speed and size. In mid ocean, one may fare almost as luxuriously as in the center of a metropolis. In place of the box-like rooms that graced the first liners, one may now obtain airy suites, with brass bedsteads and upholstered furniture. Comfort is assured even in the least desirable staterooms; -- there are running water, perfect ventilation, excellent service, and in every other detail a decided contrast to ocean travel thirty years ago.

Only a few years ago, the conventional dimensions of a stateroom were six by six feet. There was no attempt at ventilation; save that in fine weather the stewards, sometimes opened the side ports. Water -- which frequently had an ancient and fish-like fragrance -- was provided from a pitcher that had a settled habit of overturning. There was no smoking room, no library, and the deck promenade was perhaps sixty feet long. Neither was there a bathroom, nor any of the other common conveniences of the present passenger ships.

Speed is still growing in the trade, and size is keeping pace.

We're creepin' on wi' each new rig— less weighs are larger power:

There'll be the loco boiler next an' thirty knots at hour.

Thirty knots an hour is by no means a vain hope, and with new improvements and developed material, the thirty knot liner need not be a mere shell like the torpedo boat -- all lungs and muscle -- hut will have plenty of room for comfort and convenience arid cargo.

Recent High Speed Records

Aside from the great Atlantic liners, the development of steam power in other craft has been proportionately great. Among the fleets of war, high speed has become a phenomenal factor, and we now have torpedo boats and torpedo destroyers capable of steaming at the rate of ordinary express trains.

The most remarkable of these craft are the Turbinia and Viper, whose engines are arranged in a new form—the Parsons rotary turbines, driven by steam under tremendous pressure.

The Viper, which is the newer of the two, has attained a gait of thirty-seven knots, or forty-two land miles, per hour. This is considerably faster than the average running time of the express trains between New York and Boston.

On her coal consumption trial, the boat logged thirty-eight miles an hour at three quarter speed, and her engineers confidently expect a still more extraordinary pace when her machinery has worn into its bearings.

In the turbine type, the steam acts directly without the converting agency of pistons, rods, and cranks. Briefly described, the steam turbine consists of a drum fastened upon the shaft, and incased by a jacket. Upon this drum are innumerable knife-like blades set at an angle.

The steam, entering the jacket, is forced against the blades, thus turning the drum, and with it the shaft. To gain the full expansion of the steam, the drum flares out, the larger end being farther from the point where the valves admit steam to the turbine.

Under full pressure, the steam turbines revolve at extraordinary speed, a fact that necessitates a new arrangement of the screws. In place of twin screws, a series of smaller screws is fixed upon the shafts, as it was found that, with the big blades going at such speed, a virtual vacuum formed, and there was no thrust against the water.

The turbine system was adapted to marine engines by the Hon. Charles Parsons, an English engineer, who is a son of the late Lord Rosse, the well-known astronomer.

The Viper is of 312 tons displacement, 210 feet long, with 21 feet beam.

In the United States, there are a number of craft for which a speed of more than thirty miles an hour is claimed, The Ellide, a launch now on Lake George, has frequently surpassed that pace over short stretches, and her builders are now turning out another under a guarantee of forty miles.

Torpedo craft made in this country rank with any in the world. One of the first of our type -- the Stiletto -- astonished the marine architects. She was built by the Herreshoffs, and for some time she ran away from every craft she tackled. One of her most famous exploits was when she circled the Hudson River steamboat Mary Powell, said to be the fastest side-wheeler in the world, when the Powell was running at full speed.

The torpedo boat Bailey, recently launched, is another typical racer. On one of her trials, she made more than 30.5 knots an hour over the measured mile, and she is expected to maintain this great speed on a two-hour stretch.

Foster, Maximilian "The Story of the Steamship" Munsey's Magazine, 1901, Pages 689 - 706.

The Story of the Steamship - Contents

Ocean Travel Steamship Voyages

GG Archives

Transatlantic Ships and Voyages

- 1870 The Ocean Steamer

- 1877Steamship Lines - Transatlantic Passenger Traffic

- 1885 The Influence of Sea Voyages Upon Women

- 1897 Twelve Days on A German Steamship

- 1899 On The Ocean: From the "Yiddish" Poem of M. Rosenfeld

- 1899 The Therapeutic Value of Ocean Voyages

1886 Development of the Steamship

Ocean Passenger Travel (1891)

Ocean Steamships (1882)

1901 Story of the Steamship (1901)

- Gambling on Ocean Liners (1890)

- Crossing the Atlantic Like A Seasoned Ocean Voyager (1904)

- The Ethics of Ocean Travel (1904)

- Who's Who On Board - The Secrets in the Passenger List (1910)

- Early Days of Trans-Atlantic Navigation (1912)

- Wreck of the RMS Titanic - First Account (1912)

- How to Get To Australia (1918)

- Passengers Travelling Abroad Fewer in Number This Season than In 1920 (1921)

- Giant Ex-German Liners Weapons in Duel of I.M.M. and Cunard for Blue Ribbon of Atlantic (1921)

- Reclassification of Older Passenger Ships in Transatlantic Trade Coming (1922)

The Dry Years - The Eighteenth Admendment

Ocean Travel Topics A-Z

- Boutique Shops & Ship's Stores

- Ocean Travel Books

- Brochures - Steamships & Ocean Liners

- Correspondence, Shipboard

- Fleet Lists of Passenger Ships

- Ships and Ocean Liners Archival Collections

- Interesting Fun Facts and Factoids

- Journeys in Steerage

- Ocean Journeys

- Other Ephemera

- Passage Contracts and Tickets

- Postcards of Steamships & Ocean Liners

- Programs and Concerts

- Provisioning Ocean Liners

- Sanitation at Sea

- Ship Passenger Lists

- Ship Publications

- Shipboard Affairs

- Steamship Captains

- Steamship Crew

- Steamship Lines

- Ship Tonnage and Measurements

- Steamship Port of Calls

- Stowaways Onboard

- RMS Titanic

- Transatlantic Voyages

- Travel Guide (1910)

- Vintage Advertisements

- Vintage Ocean Liner Menus