Wreck of the RMS Titanic - First Account

Note.—The following account of the wreck as published in Scientific American, is so complete and so fully expresses our own views that we commend it to the careful attention of our readers.

IN the long list of maritime disasters there is none to compare with that which, on Sunday, April 14th, over-whelmed the latest and most magnificent of the ocean liners on her maiden voyage across the Western Ocean.

Look at the disaster from whatever point we may, it stands out stupefying in its horror and prodigious in its many sided significance.

The Titanic stood for the "last word" in naval architecture. Not only did she carry to a far greater degree than any other ship the assurance of safety which we have come to associate with mere size; not only did she embody every safeguard against accident, known to the naval architect.

Not only was there wrought into her structure a greater proportionate mass of steel than had been put into any, even of the recent giant liners; but she was built at the foremost shipyard of Great Britain, and by a company whose vessels are credited with being the most strongly and carefully constructed of any afloat.

To begin with, the floor of the ship was of exceptional strength and stiffness. Keel, keelson, longitudinals and inner and outer bottoms, were of a weight, size and thickness exceeding those of any previous ship.

The floor was carried well up into the sides of the vessel, and in addition to the conventional framing, the hull was stiffened by deep web frames—girders of great strength—spaced at frequent and regular intervals throughout the whole length of the vessel.

Tying the ship's sides together were the deck beams, 10 inches in depth, covered, floor above floor, with unbroken decks of steel. Additional strength was afforded by the stout longitudinal bulkheads of the coal bunkers, which extended in the wake of the boiler rooms, and, incidentally, by their watertight construction, served, or rather, in view of the loss of the ship, we should say were intended to serve, to prevent water, which might enter through a rupture in the ship's outer shell, from finding its way into the boiler rooms.

In all probability a massive, projecting, underwater shelf of the iceberg with which she collided tore open several compartments of the "Titanic, the rent extending from near the bow to amidships. The energy of the blow, 1,161,000 foot-tons, was equal to that of the combined broadsides of the "Delaware" and "North Dakota."

As a further protection against sinking, the Titanic was divided by 15 transverse bulkheads into 16 separate watertight compartments; and they were so proportioned that any two of them might have been flooded without endangering the flotation of the ship.

Furthermore, all the multitudinous compartments of the cellular double bottom, and all the 16 main compartments of the ship, were connected through an elaborate system of piping, with a series of powerful pumps, whose joint capacity would suffice to greatly delay the rise of water in the holds, due to any of the ordinary accidents of the sea involving a rupture of the hull of the ship.

Finally there was the security against foundering due to vast size—a safeguard which might reasonably be considered the most effective of all. For it is certain that with a given amount of damage to the hull, the flooding of one compartment will affect the stability of a ship in the inverse ratio of her size—or, should the water-tight doors fail to close, the ship will stay afloat for a length of time approximately proportional to her size.

And so, for many and good reasons, the ship's company who set sail from Southampton on the first and last voyage of the world's greatest vessel believed that she was unsinkable.

And unsinkable she was by any of the seemingly possible accidents of wind and weather or deep-sea collision. She could have taken the blow of a colliding ship on bow, quarter or abeam and remained afloat, or even made her way to port.

Bow on, and under the half speed called for by careful seamanship, she could probably have come without fatal injury through the ordeal of head-on collision with an iceberg.

But there was just one peril of the deep against which this mighty ship was as helpless as the smallest of coasting steamers—the long, glancing blow below the waterline, due to the projecting shelf of an iceberg.

It was this that sent the Titanic to the bottom in the brief space of two hours, and it was her very size and the fatal speed at which she was driven, which made the blow so terrible.

The Titanic, with the sister vessel Olympic, set the latest mark in the growth of the modern ocean liner toward the ship one thousand feet in length. The Britannia of 1840 was 207 feet long; the Scotia of 1862 was 379 feet and the Bothnia of 1874, 420 feet long.

The Servia in 1881 was the first ship to exceed 500 feet with her length of 515 feet. In 1893 the Campania carried the length to 625 feet; and the first liner to pass 700 feet was the Oceanic, whose length on deck was 704 feet.

The Mauretania was 10 feet short of 800 feet; and then with an addition of nearly 100 feet the Olympic and Titanic carried the over-all length to 882.5 feet; the tonnage to 46,000 and the displacement to 60,000.

The indicated horse-power of the Titanic was 50,000, developed in two reciprocating engines driving two wing propellers and a single turbine driving a central propeller.

The ship had accommodations for a whole townful of people (3,356, as a matter of fact), of whom 750 could be accommodated in the first class, 550 in the second, and 1,200 in the third. The balance of the company was made up of 63 officers and sailors, 322 engineers, firemen, oilers, and 471 stewards, waiters, etc.

WARNED OF THE ICEBERG PERIL

When the Titanic left Southampton on her fatal voyage she had on board a total of 2,340 passengers and crew. The voyage was uneventful until Sunday, April 14th, when the wireless operator received and acknowledged a message from the Amerika, warning her of the existence of a large field of ice into which her course would lead her toward the close of the day.

The Titanic had been running at a steady speed of nearly 22 knots, having covered 545 miles during the day ending at noon April 14th; yet, in spite of the grave danger presented by the ice field ahead, she seems to have maintained during Sunday night a speed of not less than 21 knots.

This is made clear by the testimony of Mr. Ismay, of the White Star Line, who stated at the Senate investigation that the revolutions which gave her full speed. She could make about 22.5 knots at full speed, and 72 revolutions would correspond to about 21 knots.

How such an experienced commander as Captain Smith should have driven his ship at high speed, and in the night, when he knew that he was in the proximity of heavy ice fields is a mystery which may never be cleared up.

The night, it is true, was clear and starlit, and the sea was perfectly smooth. Probably the fact that conditions were favorable for a good lookout, coupled with the desire to maintain a high average speed on the maiden trip of the vessel, decided the captain to "take a chance."

Whatever the motive, it seems to be well established that the ship was not slowed down; and to this fact and no other must the loss of the Titanic be set down. Had the Titanic been running under a slow bell, she would probably have been afloat to-day.

THE FATAL BLOW

There were the usual lookout men at the bow and in the crow's nest, and officers on the bridge were straining their eyes for indications of the dreaded ice, when the cry suddenly rang out from the crow's nest, "Berg ahead" and an iceberg loomed up in the ship's path, distant only a quarter of a mile.

The first officer gave the order "Starboard your helm." The great ship answered smartly and swung swiftly to port. But it was too late. The vessel took the blow of a deadly, underwater, projecting shelf of ice, on her starboard bow near the bridge, and before she swung clear, the mighty ram of the iceberg had torn its way through plating and frames as far aft as amidships, opening up compartment after compartment to the sea.

Thus, at one blow, were all the safety appliances of this magnificent ship set at naught! Of what avail was it to close water-tight doors, or set going the powerful pumps, when nearly half the length of the ship was open to the in-pouring water. It must have taken but a few minutes' inspection to show the officers of the ship that she was doomed.

And yet that underwater blow, deadly in its nature, would scarcely have been fatal had the ship been put, as she should have been, under half speed. For then the force of the reactive blow would have been reduced to one-fourth.

The energy of a moving mass increases as the square of the velocity. The 6o,000-ton Titanic, at 21 knots, represented an energy of 1,161,000 foot-tons. At 10 knots, her energy would have been reduced to 290,250 foot-tons.

Think of it, that giant vessel rushing on through the ice-infested waters, was capable of striking a blow equal to the combined broadsides of the twenty 12-inch guns of the Delaware and North Dakota, each of whose guns develops 50,000 foot-tons at the muzzle!

Little wonder is it that the ripping up of the frail 3/4-inch or 7/8-inch side plating and the 10-inch frames of the Titanic had little retarding effect upon the onward rush of the ship. So slight, in proportion to the enormous total energy of the vessel, was the energy absorbed in tearing open the hull or the bottom, or both, that the passengers were scarcely disturbed by the shock.

Newton's first law of motion "will be served."

But had the speed been only one-half and the energy one-fourth as great, the ship might well have been deflected from the iceberg before more than two or three of her compartments had been ripped open; and with the water confined to these, the powerful pumps could have kept the vessel afloat for many hours, and surely until a fleet of rescuing ships had taken every soul from the stricken vessel.

There is remarkable unanimity of testimony on the part of the survivors as to the slight nature of the shock; and this, coupled with the universal confidence in the unsinkability of the vessel, and the perfect quiet of both sea and ship, contributed no doubt to the marvelous absence of panic among the passengers.

The wireless again, as in the case of the Republic, proved its inestimable value. The collision occurred at 11.40 Sunday night in latitude 41.10 north, longitude 50.14 west.

The call for help was heard by several ships, the nearest of which was the Carpathia, which caught the message at 12:35 a. m. Monday, when she was 58 miles distant from the Titanic. Setting an extra watch the captain crowded on all speed, reaching the scene of the disaster by 4 A. M.

THE MOCKERY OF THE BOATS

Meanwhile, with the ship sinking swiftly beneath them, there remained as a last hope for that hapless multitude the boats. The boats! Twenty in all, with a maximum accommodation of say 1,000 for 2,340 human beings!

A BLOT ON THE BRITISH HOARD OF TRADE

For years the British Board of Trade, renowned the world over for the jealous care with which it safeguards the life of the individual, has been guilty of the amazing anomaly of permitting the passenger ships of the vast British merchant marine to put to sea carrying boat accommodation for only one out of every three persons on board.

The penalty for such unspeakable folly, we had almost said criminal and brutal negligence, may have been long delayed; but it was to come this night in a wholesale flinging away of human life, which has left a blot upon this institution which can never be effaced !

We can conceive of no other motive than that of commercial expediency, the desire to reserve valuable space for restaurants, sun parlors or other superfluous but attractive features of the advertising pamphlet and the placard, for this criminal reduction of the last resource of the shipwrecked to so small a measure.

No practical steamship man can claim that the provision of boat accommodation for the full complement of a ship like the Titanic was impracticable. The removal of deck-house structures from the boat deck of the ship, and the surrender of this deck to its proper uses, would give ample storage room for the sixty boats, more or less, which would be necessary.

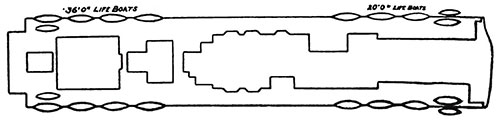

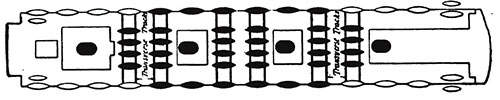

We present herewith sketches of "boating" problem, in which the number of boats on the Titanic has been raised from 20 to 56, and the accommodation from about 1,000 to about 3,100.

Boat deck of "Titanic" showing 20 boats carrying about 1000 passengers.

Plan of boat deck showing suggested accommodations for 56 boats carrying about 3100 passengers

The boats are carried continuously along the whole length of the boat-deck rails, and between each pair of smokestacks two lines of four boats each are stowed athwart-ship.

The chocks in which these boats rest are provided with gunmetal wheels, which run in transverse gunmetal tracks, countersunk on the deck.

As soon as the boat at the rail is loaded and lowered, the next boat inboard is wheeled to the davits and loaded, ready to be picked up and swung outboard as soon as the tackle has been cast loose from the boat that has been lowered.

This method has the great advantage that if the ship has a heavy list, practically the whole of the boats can be transferred to the low side of the ship.

"But," says the shipping man, "all this means heavy top weights, the loss of valuable space, and heavy costs for installation and maintenance;" to which we reply, in the words of a certain venerable book, "By how much, then, is the life of a man worth more than that of a sheep!"

Never, surely, in all the annals of human heroism, was there written a chapter at once so harrowing and inspiring as that which was gathered by the press from the pitiful remnant of that night of sacrificial horror. We turn from its heartrending story with a new sense of the God-like within and an exultant faith in the eternal lift of the human race.

Piecing together what the survivors witnessed from the boats, it is easy to understand the successive events of the ship's final plunge. The filling of the forward compartments brought her down by the head, and, gradually, to an almost vertical position.

Here she hung awhile, stern high in air, like a huge, weighted spar buoy. As she swung to the perpendicular, her heavy engines and boilers, tearing loose from their foundations, crashed forward (downward); and, the water pressure increasing as she sank, burst in the so far intact after compartments.

It was the muffled roar of this "death rattle" of the dying ship that caused some survivors to tell of bursting boilers and a hull broken apart. The shell of the ship, except for the injuries received in the collision, went to the bottom intact.

When the after compartments finally gave way, the stricken vessel, weighted with the mass of engine and boiler-room wreckage at her forward end, sank, to bury herself, bows down, in the soft ooze of the Atlantic bottom, two miles below.

There, for aught we know, she may at this moment be standing, with several hundred feet of her rising sheer above the ocean floor, a sublime memorial shaft to the six-ten hundred hapless souls who perished in this unspeakable tragedy!

"Wreck of the White Star Liner 'Titanic', in The American Marine Engineer, Volume VII, No. 5, May 1912, Pages 7-9