Crossing the Atlantic Like A Seasoned Ocean Voyager

So cheap are the ways of trawling nowadays that you can take a Summer run over to London-town and back for no more than it costs you to stay at home. This is not a fabrication: it is the truth, which few persons realize.

Most of us have the notion, bottled up tight in our heads, that the Atlantic trip requires a fortune. It doesn't. It may have done so when our grandfathers went a journeying, but today Europe can really be seen for almost a song. A lot of people, with a little grit and a knack for getting along, are traveling over seas every Summer on a pocketbook so slim as would make you gasp. A splendid time they have, too. And this is how some of them do it.

There is the tramp's ocean route. It is the cheapest, so cheap indeed that it not only doesn't cost you a shilling, but you came home with a shilling or two more than you left with. And you don't have to be a tramp, either, to do it. Many a college man has done it, and is doing it every Summer; also many a fellow, who isn't a student, but who has the adventurous spirit in him, and is willing to stand a few hard knocks for the fun that results.

Photo 01: Last Farewells To The Ocean Voyager At The New York Pier

The trip is accomplished by working your way over on a cattle-ship. Each week several of these boats sail from New York and Boston, and they take with them, to feed the steers, a gang of men. It is a pretty tough-looking gang usually, made up of hoboes, crooks and bad pennies of all descriptions, but in the Summertime it is rendered a little mere presentable by the presence of a respectable mechanic or two in search of new fields, and by odd groups of college boys looking for sport.

The work is not over hard, and at least half the day is free. The eating and the sleeping part of the enterprise is the least pleasant. The berths for the "stiffs," as the cattle-punchers are called, are way aft, down deep in an ill-smelling, inferno sort of a hole, just over the pounding steering-gear, and the food is apt to be salt junk and big hunks of lumpy bread. But to those who know the tricks of the trade, these little drawbacks present no terrors.

They are easily got round by using for a bed the clean bales of hay that are stacked up where the fresh air is to be had, and by standing in with some cook in the galley for an occasional "hand-out" of odd titbits left over from the officers' mess.

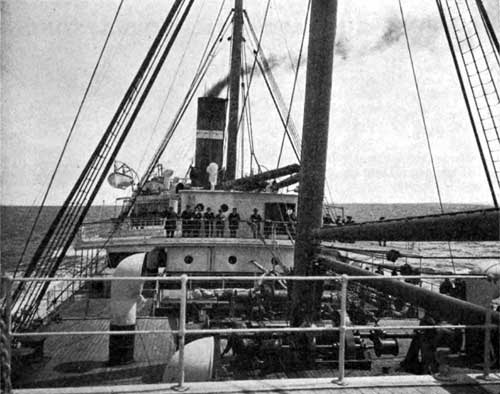

Photo 02: AMID THE MYSTERIOUS VASTNKSS OF THE MIGHTY OCEAN

View Of Top Deck Of Ocean Liner

When the voyage is ended, either at Liverpool or London, the munificent sum of ten shillings (two dollars and a half) is given to each cattleman and a pass back on some returning ship of the company's. If you take fifty or seventy-five dollars along, you can stay on the other side for three or four weeks, "doing" London. Paris and perhaps Brussels and Holland. If you start penniless, why then you come back with your pass as a gentleman of leisure on the next ship.

So there YOU are. Over the Atlantic and back for nary a cent.

In the scale of Atlantic travel, the next cheapest way to go is, of course, steerage. This is by no means as bad as it sounds, although, on the other hand, it is not all beer and skittles. The steerage conditions of thirty or forty years ago, when they herded you below decks like cattle into one common room, minus privacy. ventilation, bedding and eating utensils, no longer prevail. The third class passengers on the big liners today travel in comparative luxury.

There are regular staterooms accommodating from two to six persons, and special ones for families. A dining-room, with crockery dishes, good food and stewards to do the serving, form an agreeable contrast to the old days when a man had to furnish his own tin cup and plate, and then rustle for himself at meal times, the food, generally insufficient and poorly cooked, being served in huge pots, from which the strongest grabbed the most.

Photo 03: Steerage Passengers Going Aboard A Transatlantic Steamship In New York

There is also, on the modem boats, a smoking room, a general lounging-room and plenty of washing facilities. It is really not half bad, especially at the price, for you can cross from New York to Liverpool nowadays for twenty-eight dollars, and if a rate-war between the different steamship lines takes place this season, as seems probable, you will be able to go all the way from America to Scandinavia for sixteen dollars.

Besides being cheap, the steerage is the place where you get all that is picturesque, romantic, pathetic and humorous. Many a writer and artist and student of sociology crosses this way to see life stripped of its uninteresting conventionalities.

Just how much of Europe can be seen with a little money, if you are willing to travel steerage, is shown by what a young fellow did last Summer on $138.07. He made a tour of eleven weeks, covering six thousand miles of water, and two thousand five hundred of land in France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. He went over third-class from New York to Cherbourg for $28; his lodgings, generally a separate room, for sixty-three nights averaged 17 cents a night; his three meals a day averaged 27 cents each.

He journeyed 1900 miles by rail on the other side for $28, and 250 miles on the Rhine steamers for $2. For street car fares, fees, admissions, laundry and guide books he spent $9.35. On his wheel, which he took, he covered over 300 miles, saving much car fare thereby, and taking in about four times as much sight-seeing as would otherwise have been possible.

By selling the bicycle at the end of his tour he made enough extra to Come back second-class instead of steerage, paying $43 for a passage on one of the German liners from Hamburg to New York. Few tourists, this young fellow claims, see as much as he did in the same period, even by spending from $800 to $1000.

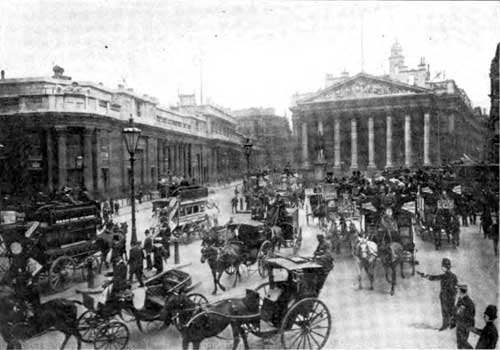

Photo 04: Mansion House Circus, In Front Of The Royal Stock Exchange, Where London Traffic Centers

Another chap, an artist, with more love for his art than cash in his pocket, went across last summer and spent six weeks on the other side for no greater amount than most young fellows lifelessly throw away on their two weeks vacation here in America. All he had when he climbed the gang-plank of the cattle-boat, on which he worked his way over, was $85. He stayed one week in London and three weeks in Paris, making little sketching trips out into the picturesque peasant districts of Normandy and Brittany.

If you are a little better endowed with worldly goods, the next best means of crossing is second-cabin. It is now everywhere acknowledged that the second-class accommodations on the biggest and best liners today are superior to the first-class facilities on the small boats of the less popular lines. An old and much traveled agent of one of the large steamship companies in New York, when asked recently by an over-particular gentleman who was picking out his saloon stateroom. what room he'd select if he were going, smiled and pointed on the plan to a room colored in red.

"Why, that's second-cabin!" exclaimed the astonished gentleman.

"Certainly," was the calm reply, "it's good enough for anybody, and there's no use wasting money just for the style of going saloon. You can get more fun out of it on the other side."

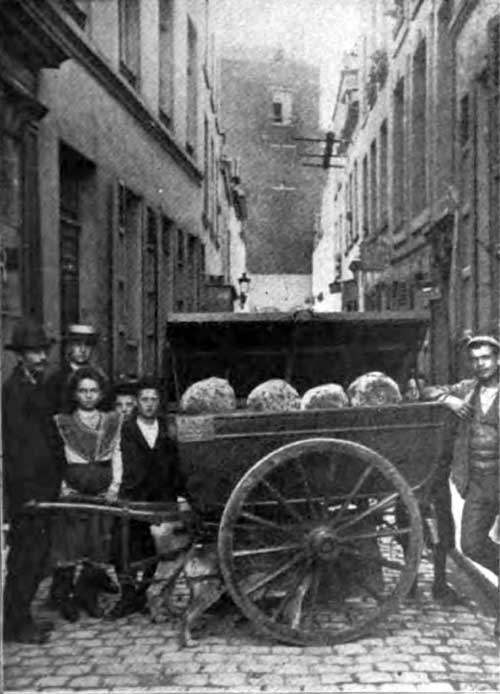

Photo 05: A Bread Cart In A Street Of Quaint Brussels

The writer himself has crossed second cabin three times, and he has yet to regret having done so. At any rate, with the money thus saved, he was able to spend an extra week or two abroad on each occasion. Of course, if you've got a large bank-account there is no reason why you shouldn't choose the finest room on the boat and have all the additional frills and fashions that are furnished with saloon accommodations, but if you stay at home just because you can't afford to go first-class, but can second. you're something of a fool, if you don't mind my saying so.

Traveling second-class the writer has made three trips abroad, each costing respectively $142.66, $193.50 and $162.75. The first lasted five weeks, the second eight weeks, and the third six and a half. On the first, London, Oxford, Chester, Warwick and several cathedral towns were taken in. On the second tour the itinerary included three weeks in London, and one in Paris, besides little side trips to the interesting places near the English and French capitals.

Photo 06: American Tourists At The Tomb Of Napoleon - Paris

On the third, Holland, a Rhine voyage, the German watering resort of Weisbaden, and London were covered. All of which simply goes to prove that if you really want to travel, if you're bound to see what you can of the world, you can do so on a very modest purse. Surely many of you must have spent the above sums time and time again without getting half the return the same amount would have yielded in foreign travel.

If you happen to have lying idle at any time two hundred or two hundred and fifty dollars you can consider yourself wealthy. The very best sort of a European tour is then yours to command. You can journey along with first-class privileges everywhere, on land or sea. Last Summer when the writer chanced to have $250 to devote to a pleasure pilgrimage over seas, he felt as if he had a fortune to dispose of. But he planned its expenditure as wisely as he knew how, making it stretch out so that this was the splendid result : Over first-class by Cunard Line, Boston to Liverpool. A day at Chester, two at Warwick, visiting both Warwick and Kenilworth Castles; two days at Stratford-upon-Avon; one week in London; one week in Paris; the same in Switzerland, taking in Lucerne and its lake trips, Interlaken. with its delightful journey over the Wengern Alp and up the great Jungfrau, and Berne. Then three days in Brussels, two in Antwerp, two in The Hague and the famous Dutch seashore resort, Scheveningen, and home again, first-class, from Rotterdam to New York.

Two months, jogging along among the celebrated sights of the Old World. And I didn't run close to the wind, either. I carried a trunk full of raiment. and suffered not at all from the humiliation of living all the time in one suit of clothes. I had a room to myself every night, and most generally it was quite as good as my own at home. I went to many a play for a shilling. and enjoyed it hugely, and as for the grand opera, I heard Calve and the De Reszkes in "Carmen," at the Covent Garden, in London, for sixty-two cents.

Photo 07: YOUR COMPANIONS. SHOULD YOU GO TO EUROPE STEBRAGE

Steerage Passenger Heading To Europe

I explored cathedrals galore from crypt to chimney top; and not a museum, so far as I know, got by me. I tipped porters, boots, waiters and smiling chamber-maids beyond number, and they were all very good to me. I bought photographs, guide-books and little souvenirs aplenty for the dear ones at home. Up the Alps I went and down the Catacombs. Everywhere. the world went nicely; no hitch, no worry, nothing to cry over. And all for $250.

Could it ever have been better invested? Certainly not in some wild-cat scheme that only brings you in a nicely engraved stock certificate to remind you forever of your folly. But travel-ah! that pays you regularly a big dividend in delightful memories, in splendid experiences, and in interesting knowledge as long as you live. Europe for $250. for $150, far $50, why, pray, stay at home and sigh?

Harper, Warren, "Across The Atlantic For A Song." The Era Magazine, Volume XIV, No. 1, July 1904, P 39-44.