Who’s Who On Board: Decoding Passenger Lists, Status, and Gossip at Sea (1890–1910)

Front Cover, SS Caledonia Saloon (First Class) and Second Cabin Passenger List, 26 March 1910. | GGA Image ID # 2336c636ed

🚢 Review & Summary: “Who’s Who On Board – The Secrets in the Passenger List”

This witty, observational essay (Alan Dale, The Great Wet Way, 1910) pokes fun at the social theater of ocean travel, using the seemingly dry passenger list to reveal how status, gossip, and aspiration played out aboard transatlantic liners. Rather than a mere roll of names, the passenger list becomes a springboard for decoding who’s important, who wants to be, and how passengers use titles, entourages, and even steamer-chair labels to craft identities at sea. The result is a lively primary-source lens on Edwardian travel culture, class performance, and the social rules that governed shipboard life.

✨ What’s Most Engaging (and Why)

The Satire of Status: The essay skewers the idea that the passenger list should be a “Who’s Who,” lamenting its lack of asterisks ⭐—and lampooning passengers who try to fix that with servants, titles, and conspicuous routines.

Gossip as Social Currency: From “honeymooners” under surveillance to the novelist collecting characters and the unproduced playwright with a trunk of scripts—gossip becomes the ship’s bloodstream, showing how narratives form in closed communities.

Democracy vs. Display: The author mocks the “democracy” of a list that prints millionaires beside budget travelers—no suite prices, no rank, no pedigree—forcing passengers to perform rank in public spaces.

Crew as Social Signals: Officers’ greetings, the doctor’s nod, the purser’s attention—these micro-gestures telegraph importance to the entire ship.

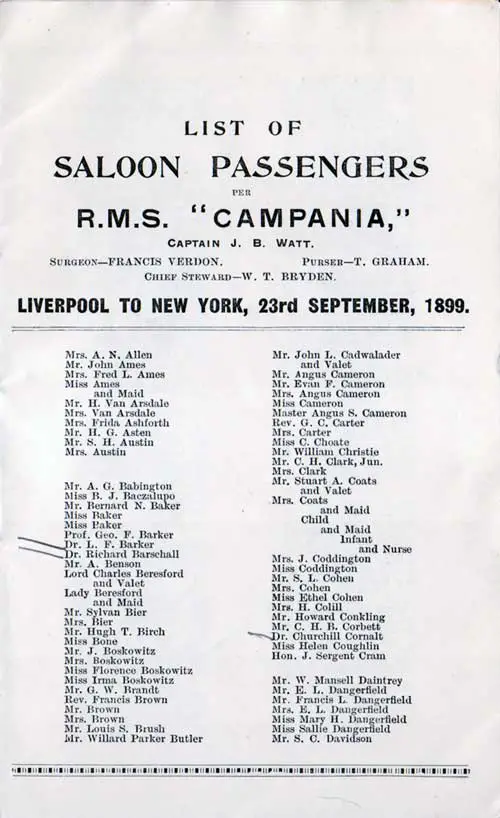

The passenger list is an important document setting forth, barely and with laconic precision, the names of your associates on the ocean trip. All biographical details are withheld so that you are kept busy during the entire voyage, uncovering them.

The passenger list is a very institution, and it has not kept pace with modern improvements. It is the same today as it was twenty years ago – the same uncommunicative and unsatisfactory chronicle of mere names. Now, if you read your Baedeker, you will discover that the compiler of that flippant and exciting record is not satisfied with merely recording the names of the hotels in the towns of visited countries, and leaving you in hopeless befuddlement at the endless array of resting-places.

Baedeker places an asterisk opposite each hotel that it guarantees to be first-class. That, of course, is a great relief. You read that Baedeker declares a particular hotel to be first-class, and you don't go there.

But on the passenger list, no names are asterisked. The steamship companies do not guarantee the quality of their passengers, which would be an easy thing to do. Instead of consulting a judicious "Who's Who" and carefully labeling any passengers who have done anything that wasn't worth doing, they pay no attention to pedigree or to social standing.

The passenger list is distinctly inferior to Baedeker. It is very cold, dispassionate, and formal. The very best people are set down cheek-by-jowl with the nobodies. There is no line on any passenger list to indicate that Mr. Jones has paid $1,500 for a suite on the upper deck. His name is as unmarked as is that of Mr. Smith, who is occupying a berth in a stateroom containing four, and who is paying the minimum rate. Such democracy is, of course, deplorable.

At the opera, for instance, you know unerringly where anybody of any consequence is sitting. Exclusive people are appropriately treated by having their exclusiveness painlessly removed. But on an ocean liner, you can be a multi-millionaire, if you like, and the passenger list will not announce the fact.

This is, naturally, very galling. It is unbearable. What is the use of being anybody if nobody knows who you are? Why extract a week from the delightful publicity of land-life, and sink it in the obscurity of ocean life?

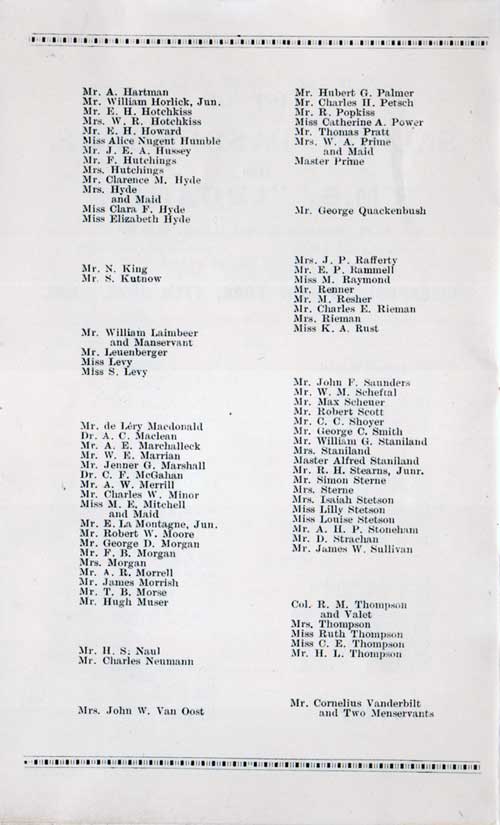

This Voyage on the RMS Lucania of the Cunard Line, on 17 June 1899, Had Notable Passengers (VIP Travelers), Including Mr. Cornelius Vanderbilt (1843–1899 or 1873–1942), a Member of the Prominent Vanderbilt Family With a Significant Impact on American Industry and Society. Miss Ruth Thompson (1887–1970) – Attorney and Michigan’s First Female Representative to Congress. Col. R. M. Thompson – Former President of the Canadian Copper Company. Mr. Neptune Blood – Connected to the High-Profile Perot Abduction Case. Mr. Louis S. Cates (1881–1959) – Renowned CEO of Phelps Dodge Corporation. Dr. C. F. Mcgahan – Director of the Aiken Cottage Sanitarium. | GGA Image ID # 23350b0af5

Lights that are hidden under bushels are indeed unfortunate. To be nobody for the whole week is dispiriting. However, efforts have been made to circumvent the passenger list, with some success. By means of these well-conceived efforts, it is possible to obtain some faint inkling of the value of your associates.

You see on the passenger list, for instance: "Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, and three children." You sniff contemptuously at the bald and poverty-stricken announcement, for below, you discover something far more winning and worthwhile in this style:

- Mr. Ponsonby-Snooks and his valet

- Mrs. Ponsonby-Snooks and her maid

- Miss Margaret Ponsonby-Snooks

- Mi. Pianjela Ponsonby-Snooks

- Master Ormsby Ponsonby-Snooks, two nurses, and a governess.

Now that catches your eye immediately. You cannot overlook it. It has warmth, color, fervor, and appreciation. It is "getting even" with the passenger list, with a vengeance. Mr. Ponsonby-Snooks, having traveled across the Atlantic for years, has, of course, realized that something must be done, for his wife's sake and for the sake of those dear children, whose transparent, juvenile minds are shaped by impressions that can never be erased.

Page from an RMS Oceanic First Class Passenger List, 8 December 1909. | GGA Image ID # 23368eafcb

Your first day, as the steamer settles down to business, is to sort out the Ponsonby-Snookses, as important people worth cultivating, if they will allow you to develop them.

You forget "Mr. and Mrs. Robinson and three children" who are plebeian enough to cross the ocean without maids and valets--who, in fact, are " doing the thing" cheaply, which is always contemptible in the eyes of those who are doing it, perhaps, more cheaply.

It is rather challenging to separate the Ponsonby-Snooks party properly. Perhaps you spend an entire morning talking with the passenger whom you have labeled " Ponsonby-Snooks "; you have decided that he is delightfully free-and-easy, and charmingly democratic for one so potent, when it is borne in upon you that the person you have buttonholed is Mr. Ponsonby-Snooks' valet. This is irritating, and you promptly cut the valet, who is inclined to be fearfully friendly next time you meet him on deck.

The effort to discover Mrs. Ponsonby-Snooks may be equally trying. After having promenaded the deck all morning with the lady, as you fondly thought, being careful to let all the other passengers see you, it gets on your nerves to learn that you have been prowling around with the nurse. There is nothing more prostrating to the really democratic mind!

You are pretty sure that you are no snob, but you do like to know the best people. You are all crowded together on an ocean steamer, and there is no reason on earth why you should not make the most of the shining hour. If you become very friendly with them at sea, you will be able to visit them on land. This exquisite fallacy is always rife on an Atlantic liner.

It is exploded every time you meet your chatty sea friends in town, and they cut you as dead as a doornail, but it grows again, like a wart, next time you cross. People with titles of any kind wear them pleasingly on the steamship. There is the baronet, whose handle comes out well on the list, and there are all sorts of American titles. There is the "Hon." So-and-So, which is misleading but nice; there are " Judge," "Colonel," "General," and "Doctor." The last is the lowest on the social scale, for it may apply to a chiropodist or an ordinary dentist, but is distinctly better than nothing at all on a passenger list that is depressingly mute on the subject of calling and standing.

A Page from the RMS Campania Saloon Class Passenger List from 23 September 1899. | GGA Image ID # 23364a9a04

For two whole days, the passengers are busy with the passenger list. They sit poring over it, and trying to "place" people. Often, as you pass, you hear somebody say, "Oh, that must be So-and-So," and a mark is made opposite your name. Your secret is discovered. You see people running around and reading the labels on unoccupied steamer chairs, and sometimes waiting until the occupants appear.

If you should happen to be sitting in the "Judge's" steamer-chair, you will be looked upon as the "Judge" until that gentleman appears to rout you out.

A significant difficulty is that labels on steamer-chairs are hidden when people are sitting on them. This is a bitter disappointment. You cannot approach a perfect stranger and say, "Kindly move your head as I want to see who you are." You are obliged to wait until mealtime, when he usually goes below. When there is a crowd on board, this isn't very pleasant. I do not say that it is impossible, for nothing is impossible if you set your mind to it.

If steamship companies cared to do the right thing, they would have the legend on each steamer chair placed high above the head of the passenger—and illuminated at night. This innovation would be dearly appreciated by a crowd that is primarily composed of the type popularly known as "rubberneck."

It is wonderful how quickly passenger gossip travels on the liner. A mere hint as to the identity of a particular person is known in a few minutes from one end of the ship to the other. Unintentionally, you yourself may spread gossip, and realize afterwards your infamy. I saw a young couple very much engrossed in each other. Her wedding ring looked new, and just for the sake of saying something, I remarked to a comrade, "Look at that honeymoon couple. They seem happy."

That man and woman had never done me any harm. Yet I had labeled them. All that morning, nobody talked of anything but that honeymoon couple. People got up and walked past them to take a look. All sorts of romances were woven around them. She was an heiress, and he was eloping with her. Everybody remembered reading about them in the papers the day before we sailed. Their case was threshed out for hours.

Unfortunately, they were not honeymooners. She was married, with a husband on board, ill in his stateroom. He was similarly situated with an indisposed wife. The four of them were all traveling together, and the non-ill ones were making the best of the situation. They had to explain this. The explanation was forced upon them by the "rubbernecks," instigated by my thoughtless stupidity!

A Couple Browses the Pamphlets Rack on Board a Steamship circa 1910. (The Scientific American Handbook of Travel, 1910) | GGA Image ID # 23362b1ae6

Honeymoon couples are a great boon to the ocean traveler. All the world loves a lover, and at sea, all the world leads him a nice life! One would think that sensible honeymooners, provided that they exist, would avoid the ocean steamer like the plague. If they reason at all, they argue that a week spent away "from everybody they know will be re-creative and appropriate.

They see themselves among a crowd of strangers, and their newlywed hearts rejoice and are glad at the sweet idea. But the people they know are not half as bad as the people they don't know. Once let their secret be guessed, and are there any honeymooners who do not look the part? - and they are watched, criticized, and gossiped about until land puts them out of their misery.

If he leaves her for a minute, his love is growing cold; if she chats with an unsuspecting passenger, she is a flirt who will never settle down; if he sleeps happily in his steamer-chair by her side, he is tiring of her; if she yawns at the endlessness of the day, married life is beginning to pall; if his voice be raised as he talks to her (he may be advising her to try and eat something at luncheon), he is developing into the usual cut-and-dried husband; if she be too indisposed to care much how she looks, she is learning how to disenchant a husband; if he doesn't call her "tootsy," he is a cold-blooded wretch; if she seems serious and gloomy, she is learning that marriage is a failure.

One's heart bleeds for the honeymooners on board ship, and there are so many of them, all trying to look usual, and never succeeding. In a crowded town, their lot would be a happier one than it is on the ship, where people are aching for romance and are bound to weave something of the sort around the honeymooners.

They analyze the poor young bride's " trousseau," and wonder what sort of clothes she will wear when he has to pay for them; they are anxious to know when he will discover that she dyes her hair and makes up her face; he must have married her for her money, or she took him because he was her last chance.

The honeymooners cannot please the passengers. Sometimes, they try. Gossip runs high, and it is inexhaustible. If the honeymooners have important names, and their wedding has been chronicled in the daily papers, people rack their brains to recall the details. Poor honeymooners! The storm rages around them, and they cannot escape it.

How Friendship Ripens On The Sea. You'll Never Know Who You Will Meet or You Just Might Find the Love of Your Life on a Transatlantic Voyage. (The Era Magazine, September 1904) | GGA Image ID # 2335ee4567

There is no shelter. If they talk to strangers, they are pestered with questions, and their remarks are reported to the other passengers. We know all that there is to know about them, and imagine the rest. Kind passengers smile affectionately at them; even the Captain is subdued with gentle deference. The Captain feels responsible for this honeymoon, and he is awfully friendly and attentive. The purser and the doctor, sometimes brusque, are never brusque to the honeymooners. They are the ship's "stars," compelled to twinkle when they would love to be obscured by some thick, protecting cloud.

Honeymooners are treated as though they had a disability, or people with some fatal disease. Passengers could not possibly be more attentive to the unfortunates irrevocably afflicted with some incurable malady than they are to the honeymooners. The honeymooners have run away from all their old friends in quest of seclusion. They find themselves confronted with new ones, who are terribly exacting, and whom they cannot flout. For while you can-and do-give your old friend a piece of your mind, you may not be candid with the new one. It is the new friend that makes the honeymooners fractious.

The important person on board the ship, whose importance has not been passenger-listed, is not satisfied to remain unknown for seven whole days. He may have undertaken the trip for rest-he says he has-but it is not restful to be unrecognized. It is distinctly annoying; one's mind must be serene. He has to do all the work that the steamship company should have done for him. He selects a gossipy passenger, which is not as difficult as you might think, and to this passenger he tells the story of his life.

He conceals nothing and does himself full justice. This is a duty that he owes to himself. The information thus obtained is immediately disseminated throughout the ship, and the important person can settle down to mere enjoyment. He becomes deliciously reticent and modest with passengers, wonders how they know so much about him, and declares that nowadays it seems impossible to travel incognito.

The lady who has written novels of which you have never heard is much sought after on board a ship. The news of her alluring avocation reaches you quickly. You ascribe the fact that you have never heard of her novels to some oversight. Later on, she tells you that she has not been "properly advertised" and has no "head for business."

The passengers gaze upon her with awe. Although everybody writes novels, tradition demands the awe that was called forth in the time when everybody didn't. The passengers actually begin to believe that they have read some of the books that she has never written, and they are very anxious to read her next, which she will never write. This lady is always seen taking notes for her new book.

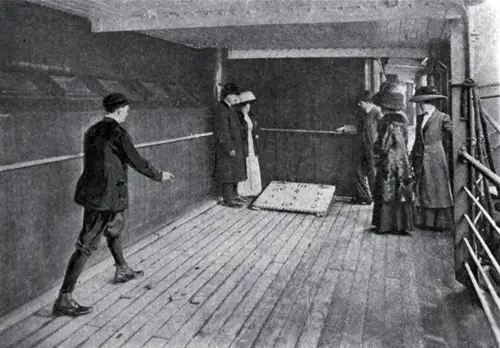

Deck Games Are a Popular Past Time During the Lengthy Voyages Across the Atlantic. (The Scientific American Book of Travel, 1910). | GGA Image ID #

She poses on deck with a sheet of paper and a pencil. She becomes very popular, for she tells every passenger that he is going to be one of the characters in her new novel. This makes a great hit. So would her book, if every passenger appeared in it. Long before we land, the lady enjoys a tremendous vogue; the stewards dance attendance upon her, and the officers say: "Good-morning" when they see her.

You can generally tell important passengers by the demeanor of the officers. The doctor and the purser doff their caps and say, "Nice day," to important passengers. Importance is a good thing, say what you will. It is easy to acquire on the ocean, where you practically begin life afresh, leaving your hideous past, your unadmirable friends, and your unappreciative relatives on shore. The absence of relatives gives a new zest to life. Who can be important with a set of abominable relatives, all with hatefully retentive memories, determined to keep a man down where he belongs?

Then there is the playwright with a trunk full of plays that have never been produced. He becomes, for the first time in his life, a poor chap, quite brilliantly important. He knows all the managers and calls them all by their Christian names. Every manager is just crazy to produce his plays, but they will not agree to his terms. He sets a high price upon himself, and what man who is worth his salt doesn't? At the concert, he makes a speech and is introduced by the chairman as "The eminent playwright in our midst."

Young girls on board, with stage aspirations, sit by him and coax him to write parts for them in his next play. On one occasion, a wag buttonholed this unproduced playwright and offered him a brilliant suggestion.

The dramatist had been very loquacious on the subject of his trunk full of plays, all good in their way.

" You want to make money? " said the wag insinuatingly. "Well, I'll tell you how. Sell your plays cheaply and realize immediately. You have probably written 100,000 plays. Sell them at a dollar apiece. That will bring you in $100,000, which is a goodly sum."

Immigrant Family Onboard a Hamburg American Line Steamer SS Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, 1910 | GGA Image ID # 2335102def

Do not imagine, however, that the most important people on board are those who chat with the passengers. That is not so. The great attraction on the steamer is the exclusive passenger who will have nothing to do with promiscuous anybody. The exclusive passenger cannot associate with any Tom, Dick, or Harry to whom he has not been formally introduced. He is generally one of a party, and the members of this party hold themselves aloof from the "dreadful people" around."

The exclusive passenger fails to notice you as you pass by. He is in a great hurry to get nowhere, and walks very quickly, with nothing in view. He sits with his exclusive tribe and takes no part in any of the ship's proceedings. You hear that he is a millionaire, and you are delighted. It is nice to be on the boat with millionaires, even if they snub you. Or, you learn that he is one of the" Four Hundred," and you are charmed. The women in the party wear dingy clothes to emphasize that their temporary and undesired associates are not worth dressing up for; the men are equally abstemious in the matter of apparel.

I sat opposite one of the alleged members of the "Four Hundred" at meals during one trip. She was very haughty. On my right side was a "variety" lady, covered with rouge and paste diamonds, who always ordered "six kinds of dessert" at the same time, and was very hungry. The society lady looked at us both as though we were mere girls. Sitting so close to the "variety" lady, I suppose that the glow of her rouge suffused me; at any rate, I seemed to be with her, and I was punished accordingly.

Once I said "Good morning," but it was not heard. The society lady used to hold forth to the companion on her right, one of her" set." Her great topic of conversation was the way her grandmother was accustomed to eating bananas. Grandma divided the skin into four cuts and made a water lily design on the banana.

The rouged" variety" lady, who would have hated to discuss her grandmother, if she had ever owned one, always looked most uncomfortable. She listened in awe. It seemed incredible to her to hear of this great lady's grandmother. I told her that, in all probability, this particular grandmother took in washing, and possibly ate the skins of the bananas in her healthy hunger. Still, she did not think I was at all funny. She watched the society dame furtively and tried to make a hit with her by putting on more rouge and paste diamonds at every meal. It was no good.

The haughty lady was completely hedged in by her own exclusiveness and would never even pass us the mustard! We certainly did not look good to her. Nor did we look at anything at all. She ignored us utterly, as people who had never been able to afford the cozy luxury of a lovely dead grandmother.

The aristocracy of money counts for nearly everything on board. As it is so easy to be a millionaire for seven days, I can never understand why everybody is not aristocratic. On land, of course, it is different, but at sea, you can be as rich as you claim to be. Moreover, you tell so many fibs on the ocean that one more or less can make no difference. It is no use being poor. It is silly. Nobody wants you to be poor. It is quite unnecessary. Be rich the instant you cross the gangplank; your creditors cannot reach you; your bank statement cannot find you; you cannot be undone, for you are undunned!

First Class Passenger Taking the Elevator. Note the Elevator Operator to Keep Up the Luxurious Accommodations. (The Scientific American Handbook of Travel, 1910) | GGA Image ID # 2335542a06

Spread the report that you are "simply rolling," and all the aristocratic democrats will love you, and make your trip one glad song. It is the only way to get to know the exclusive people on board or savor the delights of affluence. Moreover, you have all your land-life in which to be poor.

Exclusive people often have children. This may not be stylish, but they have. The exclusive child never plays with the other children.

"Mother told me not to speak to anybody," it says, with adorable candor, and it refuses all offers of candy. It is a nice little thing. The exclusive people seem to have the most miserable time enjoying themselves. They do not talk much among themselves. They are studying us all, as we study the steerage. They have never seen anything quite like us before. If we are jolly, they look shocked and bored.

Meet the Senior Officers of the ship Standing on Deck of the SS New York of the Hamburg-American Line, 1905. | GGA Image ID # 2335b86149

They are not interested in anything at all, except the Captain. They appear to have "secrets" with the Captain. They sit at the Captain's table, always. I have never yet discovered how exclusive people manage it, but they are always comfortably settled at the Captain's table. They appear to be known intuitively and honored with seats near the king of the ship. They may provide their pedigree to the company when they purchase their tickets.

It has always been a mystery to me. The Captain is usually a very jolly fellow and a nice companion; one always feels sorry that he has to entertain the exclusive people. It must be a trying ordeal. Sometimes he seems to wriggle out of it, but not often. They talk to him very affably, and he probably knows more about their grandmothers than the grandmothers ever knew.

A Captain's life is not all beer and skittles. He may cherish a secret yearning for the rougey-cheeked variety artist. Still, cruel convention ties him to the lady whose grandmother's specialty was peeling bananas.

Sometimes, and not at all infrequently, the delightful odor of " scandal" is scented on board, and then we do enjoy ourselves. It is whispered that a particular passenger is no better than she ought to be, and then we do sit up and notice. The poor thing happens to have high spirits, and she declines to mope.

An awful rumor is spread that she smokes in her stateroom. Somebody passed by her cabin and detected the telltale cigarette in the process of being whiffed. Also (and this is whispered in dead secrecy), the steward has been seen carrying cocktails to her room. We are all on the qui vive. What shall we do? Shall we warn people? Shall we cut her dead?

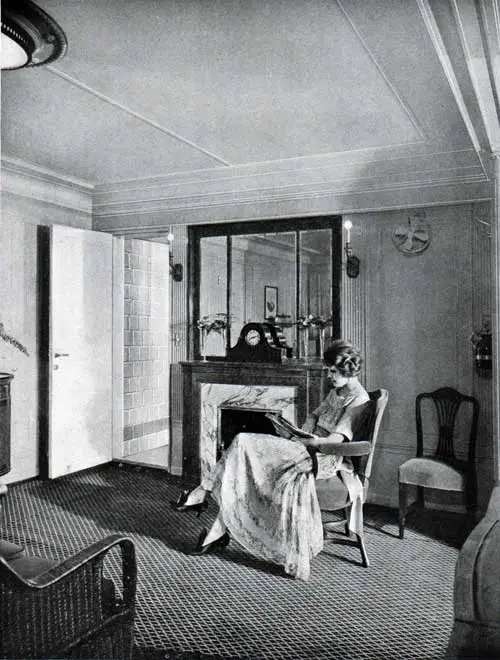

A Young Woman Relaxes in the Sitting Room of a Suite on the Giant Steamship SS Leviathan of the United States Lines, 1923. | GGA Image ID # 2335c78573

The New England spinster is for immediate action. She feels that she owes it to herself and to the state of Massachusetts. Of course, the refractory passenger is a foreigner. American women do not smoke or drink cocktails. They all say so; therefore, it must be true. The situation is exciting.

All the women contemptuously treat the object of this discussion. She is consequently forced to devote all her time to the men, which must be fearfully galling. They flock round her banner, and one would actually think that she liked it. She positively seems to do so. She talks, laughs, and promenades the deck, and has no unoccupied time at all, which must be really dreadful. The lips of the women curl as they see her. The creature is unabashed.

The New England spinster says that she wouldn't be in her boots for worlds! As the New England spinster squeezes into a NO.7, and the merry lady is loose in a NO.3, this appears to be an unnecessary statement. It is, of course, merely metaphorical.

The merry lady gives the ship something to talk about, and the ship is really grateful, though it doesn't know it. There is nothing duller than a crossing without scandal, and among the many innovations that the steamship companies will introduce is the self-raising scandal that can be enjoyed without any effort of the imagination. It is sometimes difficult to brew scandal among people who are usually on their best behavior. Then, passengers are at a dead loss.

Widows are awfully nice to have on board. The jolliest people on the boat are widows, and at sea, they are particularly attractive. At sea, also, they are invariably" wealthy widows." You never hear of a transatlantic widow who is poor. She is always living on her ample income and is free from all care. If you cannot weave a little scandal around the wealthy widow, then you are no good at it at all.

You are quite lacking in imagination. Widowhood gives a woman a cachet on the ocean steamer that nothing else could give her, and it is her own fault if she does not enjoy herself. As soon as the women passengers start wondering whether she has ever really been married, and that is but a matter of a few hours, the widow realizes that the trip is going to be nice.

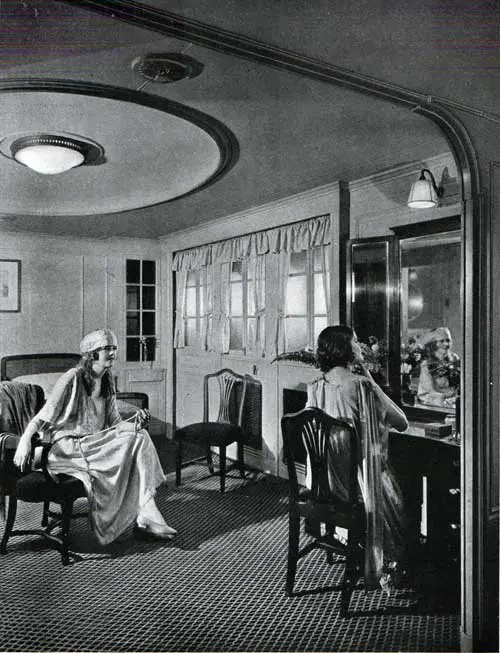

Women on Board Relaxing in Their Suite, Perhaps Talking About Some of the Other Passengers They Have Met on the Voyage. (The Steamship Leviathan, 1923) | GGA Image ID # 2335e4fb04

Maids and valets are very useful on board, as soon as they recover from mal de mer. (They are usually very ill, and for a long time.) They are helpful because they talk. They are sources of enticing information, mainly when they belong to the elite--and they generally do. The mistress says nothing, but the maid tells the truth! The master is silent, but the valet discloses all that is necessary to know!

On one trip, there was a singularly exclusive lady on board, and she despised us all. But before we landed, we knew how much rent she paid, what her meat bills were, who catered for her well-known dinners, and whether she was good to her mother. We knew, furthermore, that she often had her clothes dyed; that when she was alone with her husband, they never partook of anything more luxurious than chops for dinner; that her "home life" was very monotonous, and that she was really bored to death.

The valet and the maid vied with each other in delivering these choice bits of information. It would be worth the while of any writer of "society news" to cross the ocean. The salt air inspires the maids and valets. I have heard stories on the ship worth "scare heads" in any newspaper. The valets and maids travel first-class, and time hangs heavily on their hands. They mingle with the other passengers and are marvelously friendly. At first, they conceal their calling, but when concealment is no longer possible, they make the best of it, like the wronged heroine in a melodrama.

Somehow or other, one can't help drawing them out, at least I can't, though I know it is most reprehensible, and when once started, they are as gods knowing good and evil. It is shameful to listen to their stories, and there is no excuse for it. Still, one feels more cheerful when the gentle maid positively asserts that the haughty dame, with the lorgnette, who has been snubbing everybody, sells all her old clothes that won't dye, and hits her husband when she is feeling lively.

It seems like the eternal justice of things. And after all, is it shameful? On land, we read such things, acquired in the same way. At sea, we acquire them for ourselves. This is a better sport. It is the difference between buying nuts already cracked and cracking them for yourself. Nurses and paid companions are of little use on board, I mean, of course, to the passengers. They cannot talk because they are always with their charges. It seems a pity. They look as though they could speak, but their time is always taken up most inconsiderately.

What becomes of all the dear friends you meet on board? Goodness only knows. For seven days, you have been so vitally interested in them, so keenly attentive to everything they had to say, that you are firmly convinced you can never quite get along without them. You have their card, and they have yours.

The exchange of visiting cards on an ocean steamer is a business in itself. Yet you rarely see them again. You think of them differently as soon as you land. They are myths and legends of the phantom week that you spent on board, a week that seems like a dead lapse in a busy life. They are ghosts, unsubstantial pictures, dream sketches, very rarely realities. They peopled a few strange days that were lopped from your activity.

You find their cards in some forgotten drawer, and you try to recall them. It is like the effort to remember a dream. If you saw them, again you would think of billows, and steamer-chairs, and rugs. They fade, like photographic proofs. They become misty and indistinct. You discover an old passenger list, and wonder "who's who."

Many of these people, so important for seven days, are now unrecognizable. The vast struggle to be somebody on an ocean steamer is not unlike the vaster struggle of real life on land. And it is as bootless, as foolish, and just as unstable. At the end of a week, the most remarkable personage on the steamer, whom you have watched and studied incessantly, who has given zest to your trip and food to your mind, is just a hallucination!

Dale, Alan, “Who’s Who On Board.” In The Great Wet Way, New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1910, Pages 63-84

🖼️ Noteworthy Images

Front Cover, SS Caledonia Passenger List (26 Mar 1910) – Sets the era’s look and feel; elegant cover design 📘 underscores why souvenir lists were kept.

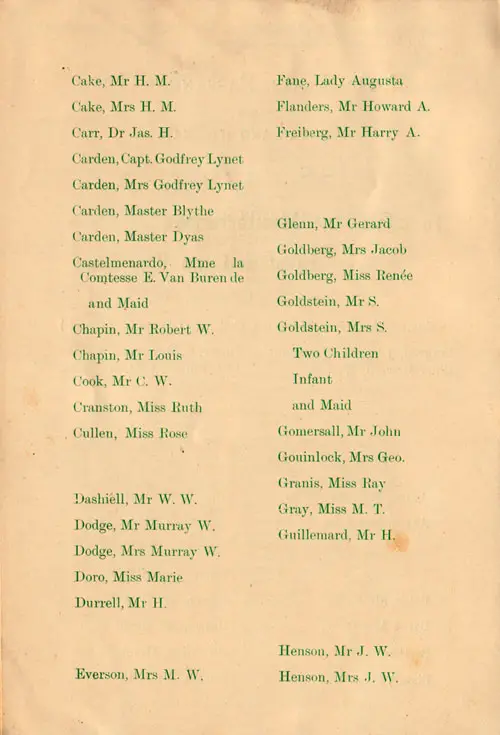

RMS Oceanic First Class List Page (8 Dec 1909) – A crisp example of how names were printed—no bios, no rank—which fuels the essay’s central critique.

RMS Campania Saloon Class Page (23 Sep 1899) – Reinforces the uniform, laconic format across premier liners.

Couple at the Pamphlets Rack (c.1910) – Visualizes the information ecosystem aboard: guides, brochures, schedules—context for how passengers “read” social cues.

Immigrant Family on HAPAG Kaiserin Auguste Victoria (1910) – A counterpoint to first-class social games; reminds students of parallel migration stories.

First-Class Elevator & Suite Scenes (1923) – Highlights the infrastructure of status (elevator operators, luxury interiors) that fostered performative hierarchies.

Senior Officers on Deck (1905) – Shows the gatekeepers of prestige whose deference signals “who’s who.”

🎓 Relevance for Teachers, Students, Genealogists, Historians, and Others

Teachers & Students:

Use the essay as a primary-source case study in social stratification, performative identity, and media literacy—how a minimalist record (the list) spawns elaborate social narratives.

Compare first-class theatricality with immigration-era realities; ask how class, gender, and nationality shape visibility and gossip aboard.

Writing prompt: “How does limited data (a name-only list) invite over-interpretation? What parallels exist on today’s social media?”

Genealogists:

Passenger lists lack biographies—but the essay explains how names became stories via gossip, titles, entourage, and officer attention. Pair with GG Archives’ souvenir lists and official manifests to triangulate identity, class of travel, and social networks.

Historians:

A sharp tool for analyzing Edwardian leisure culture, maritime modernity, and class performance aboard liners.

Collectors & Curators:

Justifies the value of souvenir lists as cultural artifacts: design, typography, and social context add interpretive heft beyond genealogical use.

⛴️ Ocean-Travel Context (Key Takeaways)

Passenger Lists as Minimalist Data: Names only—no rank, no wealth markers—forcing travelers to “perform” status through visible signs (servants, seats, table placements).

Shipboard Sociology: Closed communities + long voyages = intense rumor cycles, identity labeling, and a craving for celebrity or scandal to “animate” the week.

Hierarchy by Ritual: Officers’ micro-courtesies and the Captain’s table operate as soft power systems that validate social standing.

✍️ For Students: Use GG Archives for Your Essay!

Instead of quoting generic summaries, cite GG Archives’ primary sources—passenger list pages, period travel handbooks, liner brochures, and photo captions. Build arguments with original images + contemporary commentary to show how minimal records spawned maximal meanings aboard ship. 💡 Pro tip: juxtapose a first-class list page with an immigrant family photo to discuss visibility and bias.

💬 Most Interesting Passages to Highlight

The “asterisk” joke (envy of Baedeker’s ratings) → critiques the passenger list’s “democracy.”

The honeymooners vignette → a masterclass in how rumor manufactures biography from nothing.

The novelist and playwright scenes → meta-commentary on storytelling economies aboard ship.

The officers as social barometers → how power signals travel faster than wireless.

🧭 Final Thoughts – Why This Article Matters 🧠

This essay transforms a humble list into a map of social performance, showing how ocean liners were stages where identities were cast, tested, and believed. For researchers and educators, it demonstrates how to read around the record—to pair passenger lists with images, guidebooks, and ephemera to reconstruct lived experience at sea. For genealogists, it’s a reminder that names on a page invite—but don’t guarantee—story; the work is to verify, contextualize, and compare.