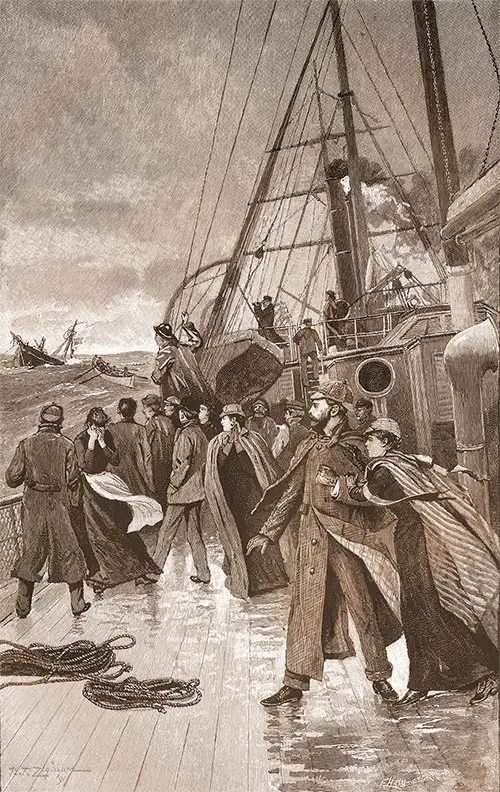

Room on the Early Steamers - Ocean Passenger Travel

A Drama of the Sea

Drawn by R. F. Zogbaum, Engraved by E. H. Del Orme

On the most unpretentious modern steamship there is room enough in the chambers to put a small trunk, and even other articles of convenience to the traveler; and one may dress, if he takes reasonable care, without knocking his knuckles and elbows against the wall or the edges of his berth.

Nowadays, too, the stateroom is usually large enough to accommodate three or four persons, while some are arranged to hold six and even eight persons.

The pioneer steamship had chambers so narrow that there was just room enough for a stool to stand between the edge of the two-feet-wide berth and the wall—mere closets.

There were two berths in each room, one above the other. By paying somewhat less than double fare a passenger given to luxury might have a room to himself, according to the advertisement of the Great Western.

Within such narrow quarters, however, everything possible was done for the passenger's comfort. A gentleman, now in business in New York, who crossed in the earliest days of the Cunard Line, and who has since sailed on the modern racers, says that the difference is by no means as great as might be expected. He puts it this way :

" The table was as good then as it is now, and the officers and stewards were just as attentive. There is more costly ornamentation now; but that aside, the two great improvements over the liners of forty-five years ago are in speed and space. There is more room now to turn around in, and the service is somewhat better."

This is a very good-humored view of the matter. It is not probable that latter - day travelers would be content to put up with narrow rooms, smoking lamps, low ceilings, and other discomforts that have been removed in recent shipbuilding. The traveler today demands more than comfort and safety.

Traveling is in the main itself a luxury, and as more and more Americans have found themselves with sufficient means to indulge in it, they have demanded more and more luxurious surroundings and appointments.

It is in response to this demand and the growth of the traffic, that within the last few years there has been placed upon the transatlantic lines a fleet of steamships that surpass in every respect anything that the world has seen.

For several years the Cunard Line enjoyed what was substantially a monopoly of the steam carrying trade between England and America, although individual vessels made trips back and forth at irregular intervals, and various and unsuccessful attempts were made to establish a regular service. The first enterprise of this kind that originated in the United States was the Ocean Steam Navigation Company.

In 1847 this corporation undertook to carry the. American mails between New York and Bremen twice a month. The Government paid $200,000 a year for this service, and the vessels touched at Cowes, Isle of Wright, on each trip.

Two steamships were built for this line, the Washington and Hermann. When the contract with the Government expired both were withdrawn and the project was abandoned.

About the same time C. H. Marshall & Co., proprietors of the Black Ball Line of packet-ships, built a steamship, the United States, to supplement their transatlantic business, but the venture proved to be unprofitable.

Then came the New York and Havre Steam Navigation Company. This line was also subsidized by the Government for carrying the United States mails between New York, Southampton, and Havre, fortnightly, at $150,000 annually.

The two steamships built for this purpose were wrecked, and two others were chartered in order to carry out the mail contract, until the Fulton and the Arago, two new steamships built for the line, were ready for service in 1856.

The most important American rival which foreign corporations have encountered in transatlantic steam navigation was the famous Collins Line.

Mr. E. K. Collins had grown up in the freight and passenger business between New York and Liverpool, and in 1847 he began to interest New York merchants in a plan to establish a new steamship line. Two years later a company which he had organized launched four vessels—the Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic, and Baltic.

They were liberally subsidized; the Government paying to the company $858,000 yearly for carrying the mails; conditions imposed being that the vessels should make twenty-six voyages every year, and that the passage from port to port should be better in point of time than that made by the Cunarders.

The Collins Line met the conditions successfully; its vessels making westward trips that averaged eleven days, ten hours, and twenty-one minutes, as compared with twelve days, nineteen hours, and twenty-six minutes by the British steamships. The vessels of the Collins Line cost upward of $700,000 each.

This was a great deal of money to put into a steamship in those days, and as the largest of the fleet was considerably smaller than the smallest of the steamships that now ply between New York and European ports, there was naturally a good percentage of cost in the appointments for the comfort of the passengers.

Many features that have since come to be regarded as indispensable on board ship were introduced by the Collins vessels. Among them none attracted more comment when the Atlantic arrived at Liverpool, at the end of her first voyage, May 10, 1849, than the barber-shop.

English visitors to the vessel, as she lay at anchor in the Mersey, saw for the first time the comfortable chair, with its movable headrest and foot-rest, in which Americans are accustomed to recline while undergoing shaving.

Another novelty was a smoking-room in a house on the after-part of the deck. In the predecessors of the Atlantic smokers had to get on as well as might be in an uninviting covered hatchway known as the " fiddley."

Ocean Passenger Travel - 1891

- Chapter 1: Overview of Transatlantic Travel

- Chapter 2: Room on the Early Steamers

- Chapter 3: The Collins Line, The Inman Company, Beginnings of the White Star Line

- Chapter 4: The Speed of the 1890 Steamships

- Chapter 5: Transatlantic Passengers and the Buildup of Fleets

- Chapter 6: Provisions and Meals on an 1890s Ocean Liner

- Chapter 7: Procedures for processing Immigrants onboard Steamships

- Chapter 8: The Importance of the Immigrant Trade