Life On Board An Ocean Liner, July 1909

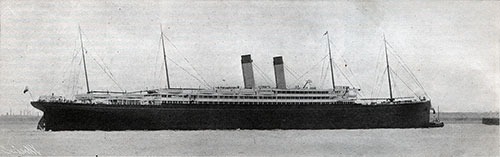

The RMS Baltic of the White Star Line. GGA Image ID # 146f5415b8

President Gompers Depicts Life On A Liner

Liverpool, July 1, 1909

Sailing from New York Saturday, June 19th, the "Baltic" brought us to Liverpool, [arriving] Sunday, the 26th. A smooth sea, sunshine in daytime, moonlight at night, very nearly record runs for the ship for every twenty-four hours -- these were the transit features of the voyage.

A sociable and democratic company of about 400 passengers; little over-dressing or other vain show; dancing evenings on the deck for the young folks; the "solution" of every form of commercial international, or Labor problems in the smoking room Parliament -- these were the social features of the first-cabin group.

No thrilling incidents occurred; no icebergs were seen, no collisions threatened, no scandals tried in the "whispering courts," nothing was to be observed more remarkable than the reading of the Sunday services of the Church of England by the Purser in the main saloon.

As my mission to Europe is largely for the purpose of making what observations of the working peoples' conditions which the time of my visit permits. I wrote to the Captain of the Baltic asking permission to go over the vessel to see how her wage-workers fared.

In reply, he sent a very courteously delivered verbal message by the Purser to the effect that the latter official would at any time place himself at my service for a visit of inspection.

Accordingly, having made an appointment at a certain hour with the Purser, I waited on him at his office, to be told that, as his time was almost fully taken up by his engagements, he could devote but twenty minutes to the inspection; but if I preferred it, he would send with me as a substitute one of the stewards.

With a steward, therefore, and an American companion, I went the usual rounds of those parts of the vessel which are shown to favored first-class passengers.

As we passed along, the guide glibly recited his well-conned lesson as to the vessel's wondrous bigness and the marvels of its operation. All of this was admirable indeed as a transporting machine designed to carry with safety a population equal to that of a considerable village.

The "Baltic" is certificated by the British and American maritime authorities to carry 426 first-class passengers, 420 second, and 1,195 third, and a crew of 370; in all, 2,411 "souls," as the expression is among seamen.

I am reliably informed that, despite this limit of passengers and crew, the "Baltic" as well as other steamers bound for the port of New York, frequently carry over 2,000 third-class passengers.

Our guide, the steward, showed us the various pantries and kitchens for each class, and the bakeshop where the bread is made to fill the "souls" of all classes.

Rather rapidly, he walked us through the second-class lounge and smoke-room, through the steerage quarters, and to the landing at the head of steep and narrow ladder-like iron stairways that led to an infernally hot place far below, judging from the fierce waves of heat that rose and enveloped us where we stood.

"Visitors never go down there," said our guide; "it's too hot!" And he led us away quickly, so quickly and determinedly that to both my American friend and myself his action signified and commanded "No admission!"

I asked where the sailormen were lodged. "In the fo'k'sel," he replied; "but visitors never go there. The sailors work four-hour watches; so the fo'k'sel always has a lot of chaps in it asleep, and visitors might wake 'em up."

This explanation seemed to voice also our guide's pity for the poor sailors; by making it he successfully kept us out of the forecastle. And in another moment, he had us back at the first-class companion-way, and was bidding us good-bye -- with thanks.

Well, of course, not being an official inspector, I had seen all parts of the ship to which one might penetrate whose relations to the company were but those of a temporary patron.

I had been treated most politely, but when back in my steamer chair I found myself musing on the probably similar superficial character, of many official "investigations." The way to truth is often blocked by polite attentions.

However, by dint of questioning, a glimpse at the life of the stewards was obtained, and their wage-scale learned; and, besides, we saw the steerage.

The stewards on the "Baltic," as on all the European Transatlantic Liners, receive 3 pounds (15 dollars) per round trip, and make at most twelve trips a year. That is, they receive in wages less than 200 dollars a year.

What the companies fail to pay the stewards in wages, the passengers are, by force of circumstances required to make up in "tips." Little wonder that the stewards faithfully "work" their charges for "tips."

In maintaining, as one of their firmest institutions, the "tipping" system, the steamship companies manifest a shrewd perception of their own interests. Tip takers rarely, if ever, strike. Every eager tip-seeker studies the short and sure route to the shilling or the pound awaiting his quest in the liberal passenger's pocket.

The tipped servant's vocabulary of lip-gratitude, his gestures of obsequiousness, his methods of forcing upon his intended victim a series of subtle and unnecessary attentions, his habitual air of profound deference -- what is all this but the practice of a profession in which the most successful need have the lest heart or manliness?

Is it not an unhappy, if not degrading, occupation, from which the great majority following it would gladly escape? Form my investigation, I have no hesitancy in answering the question in the affirmative. And they may -- nay, will -- become organized in the protective fold of the Trade Union movement.

The time will surely come when, as is already the case in certain English systems of restaurants, the signs will go up in ocean steamships, "No tips allowed!"

Then will the relations between passenger and steward be those worthy of man to man, each honoring his own position and the position of the other, and each dealing with the other without deceit -- a relationship which, though not impossible, is difficult now.

Meantime, the steamship companies make a pretty penny out of the stewards' tips; for it is not to be forgotten that the passengers' tips go really, not to the steward, but to the treasury of the line which is relieved of paying him his wages.

With, say 500 passengers, first and second class, each on the average giving then dollars for tips on a voyage, $5,000 is added to the dividends of the stockholders.

In addition to all this, there is deducted from the fifteen dollars per month paid to the stewards one shilling and nine pence (43 cents) for "breakage;" and this deduction is made every month without regard as to whether anything is broken or not.

Making inquiries in Liverpool, one of the men not only confirmed this fact, but added, "Yes, it is true; and the stewards seldom break anything. Indeed, the stewards pay for and ought to own, not only the glass and crockery, but also the silverware on the ships."

Not a bad stroke of business, this, and requiring less skill than the work of "confidence" men and professional gamblers in the steamer's smoke-room. And that worm, the passenger, has never yet turned!

In the engine room, the stokers and coal-passers and trimmers work four hours on and eight hours off. The stokers receive $22.50 and the pursers and trimmers $20.00 per month.

I was unable to see their sleeping quarters; but their labor representative in Liverpool told me that their "bunkrooms" were anything but models for light and ventilation; that the narrow compartments in which these men sleep are at fully Turkish bath heat temperature.

I saw the place where they eat. It is a small, narrow compartment, and may be likened to a damp, hot stable. Benches and tables are of the rudest possible construction. Those I saw at a meal had bread, tea, and a sort of stew. The "Baltic" has sixty of these men.

The thirty-six sailors work four hours on and four off; they are paid $20 per month. Their bunks are ranged round the forecastle, and they were sleeping in their clothes when I saw them; the discolored mattresses and blankets looked ready for the rag-shop or the disinfecting chamber.

On contemplating the lot of the sailors, stokers, and coal-handlers of a steamship, one asks himself how it is that men can be found who will consent to get down to such dreary, painful, and ill-requited toil, performed under such hard conditions.

As a fact, every man to whom escape is possible must flee from that sort of life. It must be the more helpless characters, from whatever cause, who remain.

One thing is to be remembered; the men are bound to work the round trip from England; for if they quit at New York, they forfeit the pay already earned.

And another, at Liverpool 22,000 dock laborers report at the gates alongshore every day seeking a job; and on the average only 15,000 find employment. The "surplus" 7,000 indicate the possible state of unemployment of maritime labor in Great Britain.

The Liverpool Dockers have a fairly well organized union, with its own bureau, impartially and in rotation assigning men to the work. It has a system of paying benefits in cases of sickness and death; it has a voice in fixing the wage scale for the men -- a better scale than obtained some years ago, low as it is today. But with the men on shipboard, it must be admitted the union sentiment at present is not strong.

As one looks at that part of the steerage to which the emigrants into the United States from the East of Europe are packed, he asks himself whether the government regulations which are applicable are yet up to a civilized standard.

To stow away for the night perhaps 100 men (or, in another compartment, women), in a low-ceiled space, in layers in iron berths, apart only far enough to admit of only crowding one's way along, is stabling them under worse conditions than cattle are ordinarily kept.

The English-speaking third-class passengers have cabins of two, four, eight berths of bare boards, it is true, but they are in great contrast in possible cleanliness and decency with the dormitories, or rather pens, in which are confined the Italians, Magyars and Russian Jews.

In these observations, obviously, I cast no special reflection upon the White Star Line. On the contrary, I am prepared to bear that its treatment of stewards and steerage passengers is even better than the average.

I but speak of facts that have passed under my own observation, with some mention of the views relevant to them, natural to one who hopes and expects better things for Labor.

My arrival in Liverpool being on Sunday, afforded me an opportunity of seeing numbers of gatherings of men at meetings in the public squares -- meetings of a religious or reform character as well as for the discussion of grievances.

Some other time I may report the specific characteristics of these meetings but for the present purpose I merely report the facts that the evidence was decisive of the great degree of poverty written upon the faces of the immense throngs which I saw.

Men with whom I discussed this matter, and upon whose statements no doubt can be entertained as to their authentic character, informed me that a tremendous mass of the workers are in a chronic state of unemployment -- that poverty and misery are rampant, and that the reason for wan faces, tattered clothing, and unshod feet, even on the Sabbath, is to be found in the tremendous number of constantly unemployed workers.

The Painter and Decorator, Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators, and Paperhangers of America, July 1909, Volume 23, Number Seven, Pp. 405 - 407