Practicing Medicine on Board Steamships - 1905

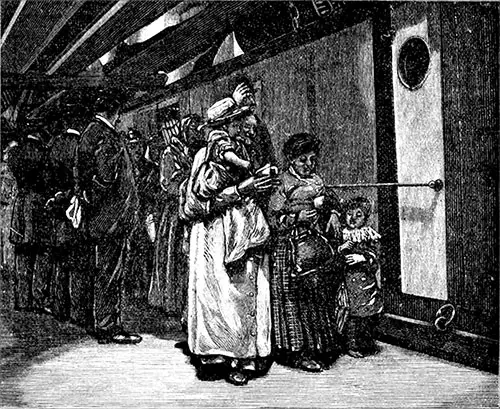

Immigrants Passing by the Ships Physician during Onboard Inspection. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, June 1892. GGA Image ID # 145c6d2ade

At 9 o'clock the round of visits commenced. In the forward port hospital, a steerage passenger was found to be ill with pneumonia, showing a temperature of 104 degrees; a steward had acute nephritis; fireman tonsillitis, and a boy a septic hand which he had brought aboard. In the after hospitals, devoted to women, there were also various cases. A young woman with pleurisy, an old lady with facial neuralgia, a child with laryngitis, and another with a bronchial cold each took up a portion of the surgeon's time.

At 10:30 o'clock came inspection. For an hour the captain, purser, surgeon and chief steward thoroughly inspected the ship from stern to stern. Every part of the vessel, from the first cabin to the third class, and from the saloon to the firemen's forecastle, was gone over; matters of ventilation, cleanliness, and order were considered and nothing, which did not meet the approbation of the officers, escaped detection. The thoroughness exercised in this inspection is such that the stewards show the greatest vigilance. Neatness, order and cleanliness have to be enforced on shipboard.

After inspection, the surgeon made his cabin calls. Fortunately, mal de mer and minor ailments were all that claimed his time. Then followed the surgery hour, at which twenty-two of the third cabin passengers and members of the crew asked for medical advice. The cases were nearly all of a minor nature -- coughs, colds, sprains, cuts and the like.

During the afternoon, the surgeon had an opportunity to get a two-hour nap. Then came the evening hospital calls, and at 8:30 o'clock, the evening surgery hour. Such was a sample day's routine. Happy was the medical man when, on reaching port after a busy week, he was able to land every person on the ship. Two went to the hospital, but both were "out of the woods" before the vessel again turned her prow homeward.

The Qualities of A Ship’s Surgeon

A very general misconception seems to exist among the medical profession and indeed among many of the laity also, as regards the professional attainments of surgeons on the transatlantic steamships. There is a widespread notion that to be a ship's doctor, one need only have a smattering of medicine, together with the vaguest ideas of surgery, and that, possessing these, a man is amply qualified to watch over the health of several hundred people among the passengers and crew of his vessel.

In point of fact, the average steamship surgeon is a fully qualified as the average physician on shore. Many of them, indeed, are men of the highest scientific attainments. The number of men who whould like to go to sea as surgeons is so great that steamship companies may pick and choose among the ablest of the younger men. It is extremely difficult nowadays for any but an exceptional physician to obtain a regular berth aboard a transatlantic liner.

It has been my pleasure during the past few years to become acquainted with many of the medical men in the American-European service, and I cannot speak too highly of their attainments.

The ship surgeon, however he may devote some of his time to the amenities of civilized life, cannot be the social butterfly he is sometimes represented as being. Indeed, most surgeons see the passengers only at the table over which they preside, and occasionally on the promenade deck. The ship surgeon leads, in fact, practically the same kind of life as his confrere ashore. He is a busy man. The larger vessels seldom carry fewer than 500 people on each trip, and in the summer months, 1,500 would be nearer the average number.

Each one of these persons, in whatever class, is privileged to call on the surgeon, at any time, day or night. And the average passenger feels free to exercise his privilege. His ailments are the same at sea as ashore, augmented by the troubles peculiar to the sea, and if anything, he is more particular when on the water than when ashore. Probably the ship's doctor listens to more tales of woe in one trip than he would hear in six months ashore.

It will be seen that the surgeon of the big transatlantic liner is no drone. His working hours are long, and much of his leisure time is taken up in the study and the perusal of the medical literature, of which he usually has a generous supply. The surgeon's library is ample and up-to-date, and his medical and surgical equipment of the best. He, therefore, who supposes that the doctor at sea is not the peer of the doctor ashore, should at once disabuse his mind of that impression. The medical profession has no more high-minded, earnest, and hard-working representatives than the ones who go down to the sea in ships.

H. Sheridan Baketel, M.D. in New York Times

Reprinted in the North German Lloyd Bulletin, Page 4, Vol. XX, No.1, July 1905, New York and Bremen. "Practicing Medicine On Board Ship"