Loss of the USS President Lincoln - 1919

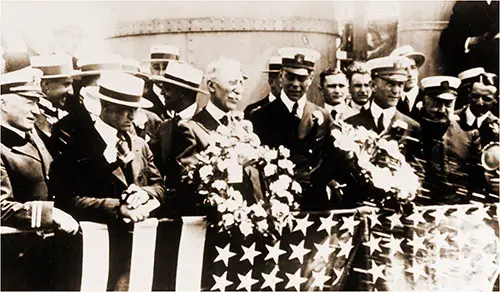

Troops of the American Expeditionary Force Boarding the Ship at Hoboken, New Jersey, Circa 1917-1918. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation, Washington, D.C. - USS President Lincoln Collection. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 60985. GGA Image ID # 18029eb99d

Of the 715 men present all told on board, it was found after the muster that three officers and 23 men were lost with the ship and that one officer, Lieutenant Isaacs, above mentioned, had been taken prisoner.

Bases at Gibraltar and in the Azores

The Mediterranean was the scene of considerable submarine activity in our first year at war, and many vessels were sunk in that region. To ensure closer co-operation with the British, French and Italian forces, a United States naval base was established at Gibraltar, Rear Admiral A. P. Niblack, assuming command November 25, 1917.

The increase in patrol and escort vessels and the Allies' improved system soon resulted in a marked reduction in sinking and a greater measure of safety to vessels sailing through those Waters.

The Azores, those Portuguese islands that formed a convenient halfway stopping place between America and Europe, became of considerable importance. A naval base was established there in January 1918, with Rear Admiral Herbert 0. Dunn in command.

U. S. Sub Chasers in Attack on Durazzo

To co-operate with the Italian and British fleets operating against Austria in the Adriatic, a flotilla of submarine chasers was sent to Corfu. In the operation of October 2, 1918, which resulted in the destruction of the Austrian naval base at Durazzo, a dozen American sub-chasers, under the command of Captain Charles P. Nelson and Lieutenant Commander E. H. Bastedo, played a conspicuous part.

They were credited with sinking one enemy submarine and the probable destruction of another; under bombardment, they screened larger ships from torpedo attack and went to a British cruiser's aid, which was torpedoed.

Sank Austrian U Boats

The British Force Commander, in a dispatch forwarded by the British Admiralty to Admiral Sims, wrote:

"I am most grateful for the valuable service rendered by twelve submarine chasers under Captain Nelson, U. S. N., and Lieutenant Commander Bastedo, U. S. N., which I took the liberty of employing in an operation against Durazzo on October 2.

They screened heavy ships during the bombardments under enemy fire; also apparently destroyed definitely one submarine which torpedoed H. M. S. Weymouth, and damaged and probably destroyed another submarine.

During the return voyage, they assisted in screening H. M. S. Weymouth and escorting an enemy hospital ship that was being brought in for examination. Their conduct throughout was beyond praise. They all returned safely without casualties. They thoroughly enjoyed themselves."

A dispatch to Admiral Sims from Rome stated:

"Italian Naval General Staff expresses the highest appreciation of useful and efficient work performed by United States chasers in protecting major naval vessels during action against Durazzo; also vivid admiration of their brilliant and clever operations which resulted in sinking two enemy submarines."

Sub Chasers Staunch and Seaworthy

More than 400 of these 110-foot submarine chasers were built, and they proved their worth in foreign as well as home waters. Young reservists, with Lieutenant (junior grade) Roscoe Howard, U. S. N. R. F., in command, brought a group of them from Puget Sound through the Panama Canal to New London, Conn., 7,000 miles.

One of these sub-chasers manned by French sailors was separated from its companions in a terrific storm alone in mid-Atlantic, given up as lost; but a month later reached the Azores, having been navigated to port with sails made from bed clothing. After repairs that Chaser, No. 28, went on across and ever since has been on duty on France's coast.

Sinking of the "President Lincoln"

The most serious loss in our transport service was that of the President Lincoln, which was sunk by submarine, about 700 miles from the French coast, on May 31, 1918. Of the 715 men aboard, all but 27 were rescued; 3 officers and i3 men being lost and one, Lieutenant Edward V. M. Isaacs, of Iowa, taken prisoner by the submarine.

31 May 1918 Lifeboats and Life Rafts Full of Survivors, after President Lincoln Was Torpedoed and Sunk by the German Submarine U-90. The Boats Appear to Be Towing the Rafts. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation, Washington, D.C. - USS President Lincoln Collection. U.S. Army Signal Corps Photograph, from the Collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command NH 103360. GGA Image ID # 1802595766

Commander Percy W. Foote, commanding officer of the President Lincoln, gave the following account of the sinking:

"On May 31, 1918, the President Lincoln was returning to America from a voyage to France and was in line formation with the U. S. S. Susquehanna, the U. S. S. Antigone, and the U. S. S. Ryndam, the latter being on the left flank of the formation and about 800 yards from the President Lincoln. The weather was pleasant, the sun shining brightly, with a choppy sea.

The ships were about 500 miles from France's coast and had passed through what was considered the most dangerous part of the war zone. At about 9 A. M. a terrific explosion occurred on the port side of the ship about 120 feet from the bow, and immediately afterward, another explosion occurred on the port side about 120 feet from the stern of the ship, these explosions being immediately identified as coming from torpedoes fired by a German submarine.

"It was found that the ship was struck by three torpedoes, which had been fired as one salvo from the submarine, two of the torpedoes striking practically together near the bow of the ship and the third striking near the stern.

The officers and lookouts had sighted the wake of the torpedoes on watch, but the torpedoes were so close to the ship as to make it impossible to avoid them, and it was also found that the submarine at the time of firing was only about 800 yards from the President Lincoln.

"The performance of Lieutenant Commander Kenyon, commanding the U. S. destroyer Warrington, and Lieutenant Commander Klein, of the U. S. destroyer Smith, deserves great commendation, as they located our position in the middle of the night, after having run a distance of about 250 miles, during which time the boats and rafts of the President Lincoln had drifted 15 miles from the position reported by radio, and it had been necessary for the commanding officers of these destroyers to make an estimate of the probable drift of the boats during that time.

The only thing they had to base their estimate on was the force and direction of the wind. The discovery of the boats was not accidental, as the course steered was the result of mature deliberation and estimate of the situation.

26 Lost with the Ship

"Of the 715 men present all told on board, it was found after the muster that three officers and 23 men were lost with the ship and that one officer, Lieutenant Isaacs, above mentioned, had been taken prisoner. The three officers were Passed Assistant Surgeon L. C. Whiteside, ship's medical officer; Paymaster Andrew Mowat, ship's supply officer; and Assistant Paymaster J. D. Johnston, United States Naval Reserve Force.

"The loss of these officers was peculiarly regrettable, as they could have escaped. Both Dr. Whiteside and Paymaster Mowat had seen the men under their charge leave the ship, the doctor having attended to placing the sick in the boat provided for the purpose, and they then remained in the ship for some unexplainable reason, as testified by witnesses who last saw them, and apparently, these two excellent officers were taken down with the ship.

Paymaster Johnson got on a raft alongside the ship, but in some way was caught by the ship as she went under, as C. M. Hippard, ship's cook, third class, United States Navy, states that he was on the raft with Paymaster Johnston and that they were both drawn under the water, but when he came to the surface Paymaster Johnston could no longer be seen.

"Of the 23 men who were lost, seven were engaged in work below decks in the forward end of the ship, and they were either killed by the force of the explosion of the two torpedoes which struck in that vicinity, or were drowned by the inrush of the water.

"The remaining 16 men were apparently caught on the raft alongside the ship and went down, probably caused by the current of water rushing into the big hole in the ship's side, as the men were on rafts which were in this vicinity.

Memorial Services at Gravesend Bay, England, on 31 May 1920, in Honor of Those Who Lost Their Lives When President Lincoln Was Sunk on 31 May 1918. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 2760. GGA Image ID # 180291827a

Feared "Sub" Would Fire on Lifeboats

"Although the German submarine commander made no offers of assistance of any kind, yet otherwise, his conduct for the ship's company in the boat was all that could be expected. We naturally had some apprehension as to whether or not he would open fire on the boats and rafts.

I thought he might probably do this as an attempt to make me and other officers disclose their identity. This possibility was evidently in the minds of the crew's men also, because, at one time, I noticed someone on the submarine walk to the muzzle of one of the guns, apparently with the intention of preparing it for action.

This was evidently observed by some of the men in my boat, and I heard the remark, 'Good night, here comes the fireworks.' The spirit which actuated the remark of this kind, under such circumstances, could be none other than that of cool courage and bravery.

"There were many instances where a man showed more interest in the safety of another than he did for himself. When loading the boats from the rafts, one man would hold back and insist that another be allowed to enter the boat.

There was a striking case of this kind when about dark I noticed that Chief Master-at-Arms Rogers, who was rather an old man, and had been in the Navy for years, was on a raft, and I sent a boat to take him from the raft, but he objected considerably to this, stating that he was quite all right, although as a matter of fact, he was very cold and cramped from his long hours on the raft.

"Fortunately, this splendid type of life raft known as the Balsa raft, as it was made of balsa wood, had been furnished the ship, and these resulted in saving a great many men who might otherwise have been lost, due to exhaustion in the water.

"The conduct of the men during this time of grave danger was thrilling and inspiring, as a large percentage of them were young boys, who had only been in the Navy for a period of a few months. This is another example of the innate courage and bravery of the young manhood of America.

715 Persons on Board the Vessel

"There were at the time 715 persons on board, including about 30 officers and men of the Army. Some of these were sick, and two soldiers were totally paralyzed.

"The alarm was immediately sounded, and everyone went to his proper station, which had been designated at previous drills. There was not the slightest confusion, and the crew and passengers waited for and acted on orders from the commanding officer with a coolness that was truly inspiring.

"Inspections were made below decks, and it was found that the ship was rapidly filling with water, both forward and aft, and that there was little likelihood that she would remain afloat.

The boats were lowered, and the life rafts were placed in the water, and about 15 minutes after the ship was struck, all hands except the guns' crews were ordered to abandon the ship.

"It had been previously planned that in order to avoid the losses which have occurred in such instances by filling the boats at the davits before lowering them, that only one officer and five men would get into the boats before lowering and that everyone else would get into the water and get on the life rafts and then be picked up by the boats, this being entirely feasible, as everyone was provided with an efficient life-saving jacket.

However, one exception was made to this plan in that one boat was filled with the sick before being lowered, and it was in this boat that the paralyzed soldiers were saved without difficulty.

Guns' Crews Held at Their Stations

"The guns' crews were held at their stations hoping for an opportunity to fire on the submarine should it appear before the ship sank, and orders were given to the guns' crews to begin firing, hoping that this might prevent further attack.

All The ship's company except the guns' crews and necessary officers were at that time in the boats and on the rafts near the ship, and when the guns' crews began firing, the people in the boats set up a cheer to show that they were not downhearted.

The guns' crews only left their guns when ordered by the commanding officer just before the ship sank. The bow's guns kept up firing until after the water was entirely over the main deck of the after half of the ship.

"The state of discipline which existed, and the coolness of the men is well illustrated by what occurred when the boats were being lowered and were about halfway from their davits to the water.

At this particular time, there appeared some possibility of the ship not sinking immediately, and the commanding officer gave the order to stop lowering the boats.

This order could not be understood, however, owing to the noise caused by escaping steam from the safety valves of the boilers which had been lifted to prevent the explosion, but by a motion of the hand from the commanding officer, the crews stopped lowering the boats and held them in mid-air for a few minutes until at a further motion of the hand the boats were dropped into the water.

"Immediately after the ship sank, the boats pulled among the rafts and were loaded with men to their full capacity, and the work of collecting the rafts and tying them together to prevent drifting apart and being lost was-begun.

Lieutenant Isaacs Taken Prisoner

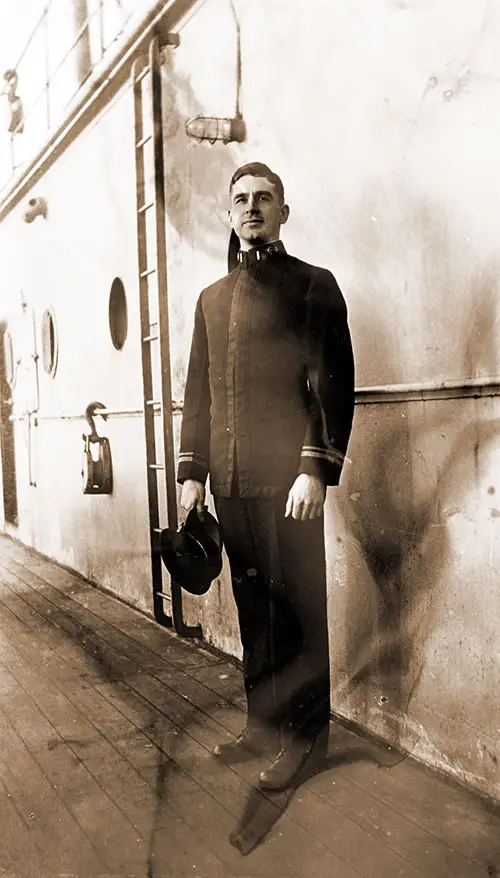

Lieutenant JG Edouard V. M. Isaacs, USN, On Board USS President Lincoln, Circa Mid-1917. the Original Image Was Printed on Postal Card (AZO) Stock. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation, Washington, D.C. USS President Lincoln Collection. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 103362. GGA Image ID # 1802da1d50

"While this work was underway and about half an hour after the ship sank, a large German submarine emerged and came among the boats and rafts, searching for the commanding officer and some of the senior officers whom they desired to take prisoners.

The submarine commander was able to identify only one officer, Lieutenant E. V. M. Isaacs, whom he took on board and carried away.

The submarine remained in the vicinity of the boats for about two hours and returned again in the afternoon, hoping apparently for an opportunity of attacking some of the other ships which had been in company with the President Lincoln, but which had, in accordance with standard instructions, steamed as rapidly as possible from the scene of the attack.

"By dark, the boats and rafts had been collected and secured together, there being about 500 men in the boats and about 200 on the rafts. Lighted lanterns were hoisted in the boats, and flare-up lights and Coston signal lights were burned every few minutes, the necessary detail of men being made to carry out this work during the night.

"The boats had been provided with water and food, but none was used during the day, as the quantity was necessarily limited, and it might be several days before a rescue could be effected.

"The ship's wireless plant had been put out of commission by the force of the explosion, and although the ship's operator had sent the radio distress signals, yet it was known that the nearest destroyers were 250 miles away', protecting another convoy, and it was possible that military necessity might prevent their being detached to come to our rescue.

Destroyers Come to the Rescue

"At about 11 P. M., a white light flashing in the blackness of the night—it was very dark—was sighted, and very shortly it was found that the destroyer Warrington had arrived for our rescue and about an hour afterward the destroyer Smith also arrived.

"The transfer of the men from the boats and rafts to the destroyers was effected as quickly as possible, and the destroyers remained in the vicinity until after daylight the following morning, when a further search was made for survivors who might have drifted in a boat or on a raft, but none were found, and at about 6 A. M. the return trip to France was begun.

Lieutenant Isaacs Bombed in U-boat

Lieutenant Isaacs, who was captured by the submarine which sank the President Lincoln, had one of the most remarkable experiences on record.

The U-boat was bombed by American destroyers, and for a time, it seemed that lie would perish with all aboard the German vessel.

Taken to Germany, after repeated attempts in which, time and again, he risked his life, he managed to escape and made his way to Switzerland. Describing his experiences. Lieutenant Isaacs said:

"The President Lincoln went down about 9:30 in the morning, 30 minutes after being struck by three torpedoes. In obedience to orders, I abandoned ship after seeing all hands aft safely off the vessel.

"The boats had pulled away, but I stepped on a raft floating alongside, the quarter deck being then awash. A few minutes later, one of the boats picked me up.

The submarine, the U-90, then returned and the commanding officer, while searching for Captain Foote of the President Lincoln, took me out of the boat.

I told him my captain had gone down with the ship, whereupon he steamed away, taking me prisoner to Germany. We passed to the north of the Shetlands into the North Sea, the Skaggerak, the Cattegar, and the Sound into the Baltic.

Proceeding to Kiel, we passed down the canal through Heligoland Bight to Wilhelmshaven.

"On the way to the Shetlands, we fell in with two American destroyers, the Smith and the Warrington, who dropped 22 depth bombs on us. We were submerged to a depth of 60 meters and weathered the storm, although five bombs were very close and shook us up considerably.

The information I had been able to collect was, I considered, of enough importance to warrant my trying to escape. Accordingly, in Danish waters, I attempted to jump from the deck of the submarine but was caught and ordered below.

Jumped from Moving Train

"The German Navy authorities took me from Wilhelmshaven to Karlsruhe, where I was turned over to the Army. Here I met officers of all the allied armies, and with them, I attempted several escapes, all of which were unsuccessful. After three weeks at Karlsruhe, I was sent to the American and Russian officers' camp at Villengen.

On the way, I attempted to escape from the train by jumping out of the window. With the train making about 40 miles an hour, I landed on the opposite railroad track and was so severely wounded by the fall that I could not get away from my guard.

They followed me, firing continuously. When they recaptured me, they struck me on the head and body with their guns until one broke his rifle. It snapped in two at the small of the stock as he struck me with the button on the back of the head.

"I was given two weeks solitary confinement for this attempt to escape but continued trying, for I was determined to get my information back to the Navy.

"Finally, on the night of October 6th, assisted by several American Army officers, I was able to effect an escape by short-circuiting ail lighting circuits in the prison camp and cutting through barbed-wire fences surrounding the camp.

"This had to be done in the face of heavy rifle fire from the guards. But it was difficult for them to see in the darkness, so I escaped unscathed.

Finally Escaped to Switzerland

"In company with an American officer in the French Army, I made my way for seven days and nights over mountains to the Rhine, which to the south of Baden forms the boundary between Germany and Switzerland. After a four-hour crawl on hands and knees, I was able to elude the sentries along the Rhine.

"Plunging in, I made for the Swiss shore. After being carried several miles down the stream, being frequently submerged by the rapid current, I finally reached the opposite shore and gave myself up to the Swiss gendarmes, who turned me over to the American legation at Berne. From there, I made my way to Paris and then London and finally Washington, where I arrived four weeks after my escape from Germany."

John Wilber Jenkins, "Loss of the USS President Lincoln." in Our Navy's Part in the Great War, New York: John H. Eggers Company, Inc., 1919, pp. 29-35.