📜 King George V’s Letter to Released British POWs (1918): A Message of Hope After Captivity

📌 Discover King George V’s personal letter to British POWs released in 1918. Learn about their experiences in German prison camps, see original images, and explore first-hand accounts of captivity and freedom. A must-read for historians, teachers, and genealogists researching WWI prisoners of war.

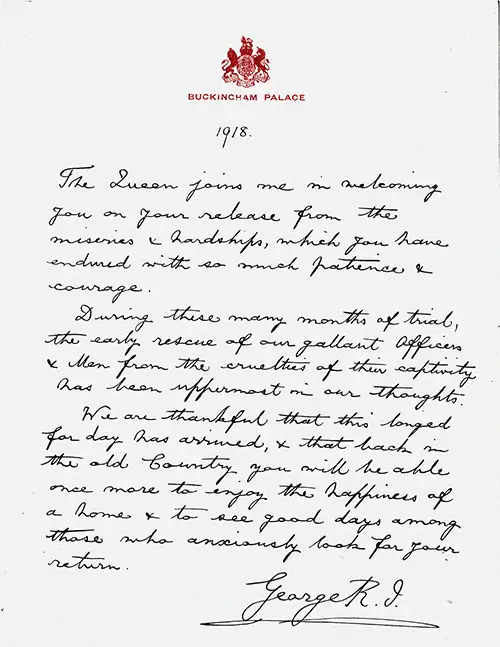

Letter to British POW's On Their Release in 1918 from King George V and the Treatment of Prisoners of War in Germany illustrated with images from In The Prison Camps of Germany: A Narrative of "Y" Service among Prisoners of War, 1920.

Letter from King George V to British POW's On Their Release in 1918. | GGA Image ID # 20d82fd657.

📜 King George V’s Letter to British POWs on Their Release (1918) 🇬🇧

🔍 A Royal Welcome After Captivity

This deeply moving and historically significant page presents the official letter from King George V to British prisoners of war (POWs) upon their release in 1918. It also provides a harrowing account of the treatment of British POWs in German camps during World War I.

Buckingham Palace, 1918

The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries and hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant officers and men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

We are thankful that this longed-for day has arrived and that back in the old country, you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home and to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return.

/s/ George R. I.

His Majesty King George V of the United Kingdom.

Information about the King George V Letter to British POW's

- Date: 1918

- From: King George V

- To: British POW's - H. Godfrey

- Dimensions of Letter: 19 x 24.6 cm

The Treatment of British POWs by the Germans

Owing to the increasing shortage of food in Germany, and to the fact that the rations in England for a long time were maintained at a reasonable level, the number oí parcels tent to German prisoners was lar smaller than that sent to British prisoners.

At first a considerable amount oí food was sent into the German prisoners' camps in England from their relations and friends residing in Great Britain, but when the shortage became acute it became necessary to prohibit this practice.

The Hague Convention also requires the captor to treat his prisoners as regards clothing on the same footing as his own soldiers The German Government claimed that it strictly observed this article and forbade the sending of clothing by the British Government.

The article was not observed at all in some German camps, and great trouble was caused by the claim, in at all events some army corps, that boots were part of a soldier’s military equipment, and that the captors were entitled to take them.

The clothing in any case supplied by the Germans was quite insufficient, and arrangements were made by which an adequate supply was dispatched according to a regular scale. Some of it went astray and some was stolen, although a good proportion reached the addressees.

In England clothing was issued when necessary to enemy prisoners, other than officers, on a regular scale, which provided for them having a sufficient change of clothing, while in both countries officers made their own arrangements for the supply of the necessary clothing.

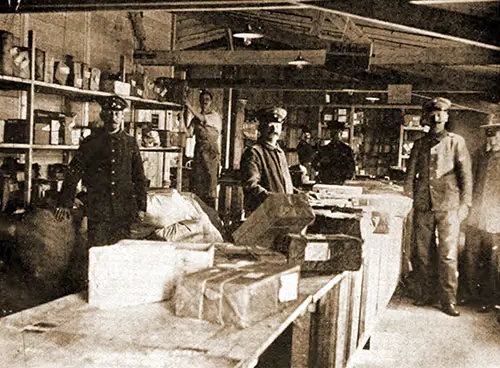

American Supplies Ready for Distribution to Prisoners at Rastatt. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 19669f4c6e

Application of the Military Law of the Captors.—Article 8 enacts that prisoners of war are subject to the laws, regulations and orders in force in the army of the captor State, a provision which gave rise to a good deal of trouble, owing, in England, to the difficulty of carrying it out strictly—while in some cases, at in Bulgaria, punishments were allowed—such as flogging—for ordinary breaches of discipline—which were quite alien to British ideas of what is permissible.

German military law is generally far more severe than British, and there is this further great difference: In Germany, officers, as well as men, maybe summarily sent to cells or awarded other severe punishments for trivial offenses, while in the United Kingdom, strictly, any offender above the rank of private should have been tried by court martial, a provision amended during the war by the substitution of military courts.

In another respect, the German code is more severe in that all sentences of arrest involved solitary confinement, while one of dose arrest, which was limited to four weeks, meant that the prisoner was confined in a dark cell with a plank bed and a bread and water diet, though these aggravations of the punishment were omitted on the fourth, eighth, and subsequently every third day, the prisoner receiving the ordinary camp diet on these days.

One punishment officially termed "field punishment," but more generally known in England as the "post punishment," caused a great outcry in that country and much resentment among British prisoners in Germany. It is provided in the German Manual of Military Law that the punishment is to be inflicted in a manner not detrimental to the health of the prisoner, who is to be kept in an upright position with the back turned to a wall or a tree in such a manner that the prisoner can neither sit nor lie down.

These last words were construed to mean tying the prisoner to a post. Sometimes, his feet were placed on a brick, which was removed after he was securely tied, and sometimes, his hands were secured above his head.

Apart from these aggravations, this punishment was in strict accordance with the captors' military law; indeed, it corresponds to field punishment No. 1 authorized by British military law and described in the rules for field punishment for offenses committed on active service made under Sec. 44 of the Army Act.

These rules authorize the keeping of the offender in fetters, handcuffs, or both, and when so kept, he may be attached by straps or ropes for a period or periods not exceeding two hours in any one day to a fixed object during not more than three out of four consecutive days and not more than twenty-one days in all.

In Germany, all prisoners must be treated as "in the field," i.e., on active service.

In one respect, German military law was less severe than the British regarding the punishments for attempted escape. The latter's greater severity arose from a misunderstanding of the expression "peines disciplinaires" in the second paragraph of the 8th Article of the Hague Convention.

This seems to have been understood on the Continent as a punishment that could be awarded summarily: arrest, open, medium, or close, for a period not exceeding six weeks.

In Great Britain, the punishment was limited to 12 months imprisonment; in Germany, it was far less for the simple offense, though charges for damaging Government property and the like frequently increased it.

The matter was discussed between the British and German Delegates at The Hague in 1917 and 1918, and an agreement was reached by which the punishment for a simple attempt to escape was to be limited to fourteen days, or if accompanied by offenses relating to the appropriation, possession of, or injury to properly two months' military confinement.

In addition to the summary punishments, death and imprisonment were punishments in both countries, which could only be inflicted by court-martial.

In some cases, the German code lays down minimum punishments of great severity, and in many of those cases, in which the infliction of very severe punishments properly raised a great outcry in England, the German court-martial had no option but to pass them.

The British military law, on the other hand, has only one offense —murder—for which there is a fixed punishment; for others, it is "such less punishment as is in the Act mentioned."

In one respect, the prisoners of both countries were never satisfied. Neither understood or appreciated the procedure of the other. The British never understood the long delays; sometimes it is to be feared deliberate, which occurred in bringing them to trial for alleged offenses, and during which they were kept under arrest, nor, owing to their ignorance of the German military code, could they understand the very severe sentences necessarily passed by courts-martial (which seem usually to have been conducted with fairness), nor the right of the prosecutor to appeal against a sentence which he considered to be inadequate.

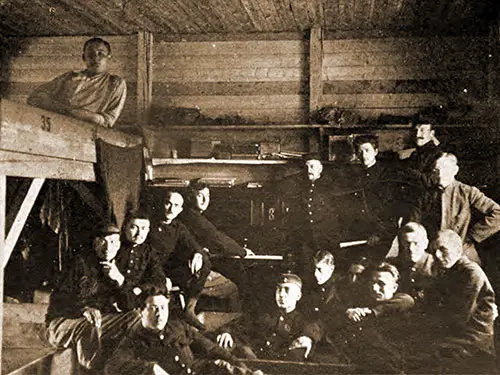

View in One of the Barracks at Göttingen. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196883fa23

On the other hand, the Germans never appreciated the British procedure, nor could they understand the absence of any right of formal appeal from a sentence, for which ample provision is made in Germany, even against the award of disciplinary punishment, a right which, oddly enough, by See. Fifty-two of the Regulations relating to it, the accused shared with the prosecutor "only when the sentence has been carried out."

Parole.—Articles 10, 11, and 12 deal with parole. In the World War, no combatant prisoners, with one exception, were allowed to leave Germany or Great Britain on parole or to reside outside the camps.

The only cases in which questions arose were about the temporary parole given when officers left their camps for a walk and the parole given by those who were interned in neutral countries.

According to British Army custom, no officer ought to give his parole; it is his duty to escape and rejoin his unit if he can. Nor can anyone below the rank of officer give a parole.

In both countries, however, officers were eventually allowed to go out for walk parties accompanied by an officer, each giving in writing a temporary written parole that he would not attempt to escape, make arrangements to flee during the walk, or do anything to the prejudice of the captor State. Parole was given upon leaving the camp and returned upon reentry.

The case of those interned in neutral countries was different. The British officers of the Royal Naval Division interned in Holland after the fall of Antwerp and were permitted to choose their residence in Groningen on parole, the men being interned close by. This privilege was withdrawn for a time, and the officers were interned in a fortress, but it was restored later.

As time went on, the Netherlands Government permitted officers to return to England and Germany on parole, on proof of the serious illness of a near relative, a concession which was afterward extended so that both officers and men enjoyed regular periods of leave, the former giving formal parole and the latter a promise to return on the expiration of their leave. In contrast, the British Government assured the men would not be employed in any work to do with war and would return at the end of their leave. Similarly, the Danish and Norwegian Governments granted leave to British and German combatants interned in their countries.

No parole seems to have been taken from those officers who were interned in Switzerland or Holland under the agreements made in 1917 and 1918 with the German Government.

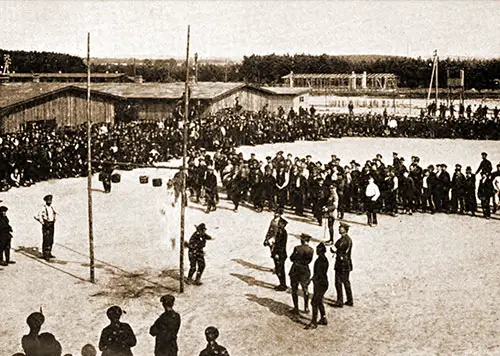

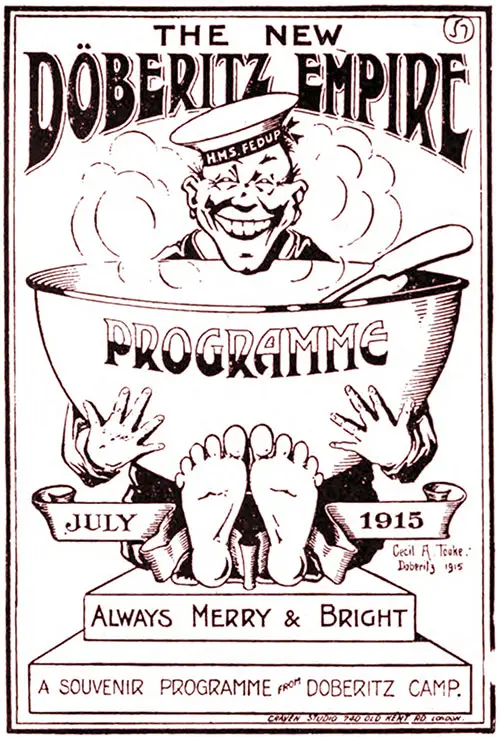

Relief Societies. Article 15 deals with societies for the relief of prisoners. Such societies did an immense amount of valuable work, which is impossible here to particularize—the American branch of the YMCA. This especially did much for the prisoners in England and Germany, who were permitted to work under the following conditions, substantially the same in both countries.

A building or tent might be erected in the camp with the consent of the general officer in command of the district or army corps. Still, nothing might be sold in it, nor could anyone be employed there except a prisoner.

A member of the association might visit the camp once a week for a definite time. He might hold services, provide materials (or games, entertainment, and employment, arrange instructional courses, provide books (subject to censorship), and write materials other than paper and envelopes. Nothing might be given to or received by a prisoner without the commandant's consent.

Recreation. The Hague Convention does not expressly provide for prisoners' leisure time occupation. Still, much of the good work done by the societies involved prisoners' recreation and education. In both countries and nearly all camps, provision was eventually made for sufficient space for recreation and exercise, but this was not the case at first.

At Haile, for instance, a German camp for officers was established in a disused factory. The only place for exercise was the space enclosed by the three buildings in which some 500 officers lived.

It measured about 100 yards by 50, and in winter, it was a morass of water and mud; in summer, it was deep in dust. In some men's camps, the space was very confined, and organized games were impossible.

But later, things improved, and in most cases, provision was made, sometimes at the prisoners' expense, for sufficient room for tennis, football, and other games.

The War Office provided facilities in England. To take two typical instances, it may be said that at Donnington Hall, for German officers, there was a considerable space in front of the house, and at Dorchester, for men, there was a large field where any games could be played.

As time went on, officers who were given temporary parole were permitted to walk outside the camp, and in Germany, in some of the larger working camps, the men were allowed out for walks on Sunday.

In England, both officers and men made their own arrangements regarding educational facilities, as they did in Germany, with the full concurrence of the authorities.

The British Social Club, Rembahn. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196f453c65

At Munster, for instance, the general officer commanding excused all students from work, and much was done by some of the prisoners in the organization of classes and lectures.

The neutral organizations, such as the American and Danish YMCA, also did a great deal in this direction, as they made sure of the German civilians in the neighborhood of the great camp at Göttingen.

Professor Stange and some of his colleagues interested themselves in the prisoners and organized the educational work in the camp. He himself had an office there, where he was accessible to prisoners and assisted them with his advice on educational matters.

He even obtained the requisites for games through the Red Cross in Switzerland. Unfortunately for them, all the British prisoners were ultimately removed from Göttingen, which had become something of a model camp.

Some of the larger employers were also very considerate in this respect, providing recreation halls and fields for playing games and even musical instruments.

At Mulheim, the Dutch visitor found that the employers had paid the expenses for the prisoners' Christmas festivities.

Letters. Article 16 was observed by both countries, except that at one time, in some of the camps in Germany, customs duties were charged on the contents of parcels. This seems to have been due to some misapprehension and was soon abandoned.

Prisoners were generally allowed to write two letters a month and a postcard every week and, in addition, a postcard in the prescribed form acknowledging the receipt of a parcel.

But later in the war, a "first capture postcard" was introduced, by which, on a printed form, a prisoner was allowed to notify his relatives of his capture, state of health, and address.

Pay.—Article 17 provides for officers receiving the same pay rate as officers of the corresponding rank in the army of the captors. This provision was not observed by the German Government, which paid subalterns 60 marks a month and other ranks rather more.

Accordingly, the British Government declined to carry out the terms of the article. It paid the German subalterns 4s. a day and other ranks 4s. 6d. Naval officers were paid according to their relative rank. An officer was required to pay for his food, laundry, and clothing, a deduction being made if he was in hospital (where, of course, he was provided with everything necessary).

An arrangement made later allowed the German Government to make a small addition to these daily pay rates. Medical officers employed in caring for sick and wounded prisoners of their nationality received the full pay of medical officers of the corresponding rank in the army of the captors.

Religious Exercises. Article 18 is designed to secure complete liberty for prisoners in the exercise of their religion, and during the World War, no real complaint was made on either side.

In the United Kingdom, German pastors who had been residents in the country were allowed to hold services in the camps, but difficulties arose, and the permission was withdrawn.

Thereupon, some pastors elected to be interned to minister to the prisoners. Later, however, the permits were issued in a modified form. English and American clergy laypeople and members of the Danish and Swiss Student Christian Movement were allowed to visit the camps, and the American branch of the YMCA provided the necessary funds.

The Roman Catholic prisoners were usually attended by the priest of the district in which the camp was situated, and they were given every facility.

Where no German-speaking priest was available, the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster charged the German priests of his archdiocese to visit the camps occasionally to enable the prisoners to go to confession and to hear a sermon in their mother tongue.

In Germany, at first, the Rev. F. Williams, who had been in charge of the English Church in Berlin, was allowed to visit the different camps and hospitals.

Arrival in Camp of French and British Prisoners. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196a042a3c

However, this permission was withdrawn, and the prisoners were left to conduct their own services, to which, except at Grossenweder Moor, no objection was raised.

A few British chaplains were captured and did good work until they were repatriated. The American branch of the YMCA and Archdeacon Nies, an American clergyman at Munich, also greatly assisted until the United States entered the war.

The German clergy also did what they could for the prisoners in many camps and hospitals. The British prisoners spoke very warmly of some of them.

The Roman Catholics' needs were more easily met owing to the presence of many priests who had done excellent work among the French prisoners. The Bishop of Paderborn (later Archbishop of Cologne) did much for the prisoners.

Moreover, Father Crotty was sent from Rome. He was permitted to minister at Limburg and Giessen, partly because he was an Irishman, and it was hoped his influence might be helpful to the Germans.

There was no regular provision for religious services in the German working camps, though Mr. Williams seems to have visited some of the larger places. In one district, a German pastor is said to have traveled around the small camps and ministered to the prisoners.

The Kricgsministerium had a standing order that prisoners should be allowed to attend the local churches at all events in the country districts.

Though valuable to Roman Catholics, this was not much use to Protestants owing to language difficulties.

At Zossen, the Germans built a mosque for Mahommedan prisoners, and generally, arrangements seem to have been made to avoid hurting religious and caste prejudices.

Medical Treatment. Up to this point, an attempt has been made to show how the provisions of the Hague Convention were applied in Great Britain and Germany. However, this Convention does not deal with everything that affects the well-being of prisoners of war.

The Geneva Convention of 1906 requires the belligerents to respect and take care of the wounded and sick without distinction of nationality. It leaves them at liberty to agree for the restoration of wounded left on the field, the repatriation of wounded after rendering them fit for removal or after recovery, and for handing over the sick and injured to a neutral State to be interned by it till the conclusion of hostilities.

What was done must be considered under three heads: the attention given (1) in the regular hospitals, (2) in the main camps, and (3) in the working camps.

Hospitals. At first, inadequate arrangements were made in Germany for the reception of seriously wounded prisoners. Still, later, well-arranged and well-equipped hospitals were available, the principal being in Berlin, Cologne, and Paderborn. However, there was a large number elsewhere.

As time went on and the pressure on Germany became increasingly acute, the supply of medical requisites became deficient. Bandages were made of paper, and drugs and anesthetics were less plentiful. Though naturally, British prisoners would fare worse than the wounded Germans, there is no evidence that the former were intentionally deprived of anything necessary for them if there was an adequate supply.

The conduct of the German doctors to the prisoners in the regular hospitals is one of the bright pages in the sad history of the World War and is worthy of their great profession.

Most of the returned British prisoners reported that the doctors were kind and humane. Many of them spoke of them in the warmest possible terms and told how the doctor had said that when a prisoner was wounded or ill, he no longer looked on him as an enemy or how, though he hated the English, he did his very best.

There were exceptions, who formed a very small minority. The large majority of German doctors worked hard, often with Infinite kindness, in the interests of those in their charge and unreservedly placed such knowledge and skill as they possessed at the disposal of the prisoners.

In the Prison Camp Compound, Münster II. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196cab69cc

Nursing in Germany was carried out by orderlies, by trained nurses, or by sisterhoods. It has varied very much. In some cases, it was good and kind, indifferent, and rough and nasty. But there is no reason to think that, in any case, it was intentionally less good than circumstances permitted.

Main Camps. The same satisfactory account of the medical arrangements in the main German camps cannot be given, even after the first disorganization was overcome. In each camp, a lazaret provided accommodation for a number proportionate to the number for which the camp was designed, but the arrangements were often very incomplete.

There seem to have been a large number of Russian doctors employed in the German camps, while a few, for short periods, English medical officers were employed—though in all cases, a German seems to have been responsible.

The nursing was mainly done by prisoner orderlies, many of whom, of course, were quite untrained, though they seemed to have done their best.

It is impossible to generalize about the conduct of the German medical staff in hundreds of camps over a period of four years, but the evidence generally suggests that the staff was humane and did all they could.

There is reliable evidence that the nature of the food provided in the German camp hospitals, as distinguished from the regular hospitals, where, until supplies became very short, it seems to have been satisfactory, was entirely unsuited for invalids.

A sick prisoner was a non-worker and, therefore, received the ordinary camp ration, less than 10 percent. This was even the ease in the typhus camps, where the requisite milk and light food for the fever-stricken patients had to be provided by the British and Allied medical officers.

There seems to have been insufficient care, at all events in the early stages of the war, to prevent the spread of tuberculosis by the segregation from the health of those suffering from that disease.

Later, however, steps were taken to effect this, and more than one place was established exclusively for tuberculous patients. At the same time, the arrangement made for their internment in Switzerland did still more to deal with this evil.

Of course, it must not be said that this mingling of the sick and healthy was deliberate. It was probably due to a lack of thought, an excuse that cannot be made for the policy adopted by the German Government of mixing all the Allies together, although this was bound in the circumstances to lead to an excessive amount of illness.

This policy was quite deliberate. In 1915, Mr. Gerard, the American ambassador to Germany, raised the question with the German authorities regarding officers and reported: "I was told that this was a political move ordered to show to the French, British, Belgian, and Russian officers that they were not natural Allies."

The commandant of the Gardelegen camp tried to enforce the observance of this regulation during the height of the typhus epidemic at that camp, but the British doctors deliberately disobeyed his direct order, with excellent results.

Though this policy did not produce any ill effects on the health of the prisoners in the officers' camps in Germany, its results, assisted by the unsanitary condition of many of them, were disastrous in the leading men's camps.

Typhus is endemic in Russia, and the Russian prisoners herded together with those of other nationalities, spread the disease till, in some camps, appalling epidemics were produced. The fever raged with great virulence at Ohdruf, Langensalza, Zerbst, Wittenberg, and Gardelegen.

Arrival of Food Parcels in Prison Camp, Münster. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196caf2f47

At Wittenberg, the camp was overcrowded and unsanitary. The washing arrangements were nothing more than troughs in the open, which, with the supply pipes, were frequently frozen during the brutal winter of 1914.

Under these circumstances, a serious epidemic broke out in December 1914. As soon as this was recognized, the whole German staff, military and medical, left and never came inside again until August 1915, by which time all the patients were convalescent.

For his services in combating the epidemic, Dr. Aschenbach, the German principal medical officer, received the Iron Cross. Many Allied and British medical officers had been improperly detained in Germany after their capture. They were dispatched to replace the German doctors, who (it is charitable to believe, in obedience to superior orders) had deserted their charges.

In Feb. 1915, British medical officers were sent to the camp, which they found to be in a state of misery and disorganization. Of the six, three died of the fever, as did several French and Russian doctors.

Notwithstanding the fact that ample supplies of medical supplies seemed to have been available, obtaining sufficient drugs and dressings was extremely difficult.

Prison Camp Program Cover at Döberitz. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196ebc8d9f

There was not even soap until one of the British doctors obtained a supply at his own expense from England, nor were beds or bedding for patients requiring hospital treatment improvised in one of the barracks until April 1915.

There were between 700 and 800 British prisoners among at least 15,000 in all, who, incredible as it may seem, were confined in an area not exceeding 10 1/2 acres. Of the British, about 300 were attacked by the disease, and 60 died.

The same story repeated at Gardelegen. As soon as it became apparent in February 1915 that something was wrong, captured medical officers were dispatched to Gardelegen, where the conditions were favorable for the propagation of disease.

Though there were empty huts in the camp, the commandant refused to allow them to be used, and the prisoners' rooms were very overcrowded. As usual, the nationalities were mixed up together.

One outdoor trough, often frozen, was allotted to each company of 1,200 men for washing, and a small hut containing at most thirty showers for x 1,000 men. The place was bitterly cold, and the heating arrangements were entirely inadequate. Consequently, the huts were kept dosed, and the atmosphere therein became foul.

Four days before the arrival of the Allied medical officers, every German had left the camp, and the commandant, standing outside the barbed wire, informed the medical officers that no person or thing was to pass out and that they were responsible for the discipline and general internal arrangement of the camp and for the care of the sick.

Dr. Weasil, the German principal medical officer, left the camp with the rest but soon afterward died of typhus. His two successors never came inside the camp.

But the third, Dr. Kranski, a civilian, came in March and devoted himself seriously to the welfare of the camp. Though he took no part in caring for the sick, he did much to improve sanitation and, in that way, aid the medical men in their work. It is unnecessary to recount the whole story of the struggles to obtain the barest requisites.

The Parcel Post Rooms at Prison Camp, Dülmen. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID #

In the tray of food, drugs, dressings, or furniture. The plague stayed after four months, during which over 2,000 cases were treated out of 11,000 prisoners, the mortality being about 15% of those attacked.

Of the 16 Allied medical officers, 12 took the disease, and three died. At the same time, of 10 French priests who devoted themselves to the care and nursing of the sick, eight were attacked, and five succumbed.

The epidemics at Wittenberg and Gardelegen, in these circumstances of gratuitous suffering and official callousness, made a world impression never likely to be entirely effaced. Still, it is only to add that the German authorities, having learned their lesson at the cost to others of so much suffering and death, did their best, too late indeed, to remedy the defects. Gardelegen and Wittenberg eventually became, if not models, at least fairly satisfactory camps.

Repatriation.--Closely allied with medical treatment is the question of repatriation and internment in a neutral country.

As early as January 1915, an agreement for the repatriation of incapacitated officers was made. At first, there was no agreement as to the degree of incapacity sufficient to entitle an officer to repatriation, but in August of that year, an agreement was reached, which was slightly amended in October.

It included 13 injuries or complaints entitling a person to be repatriated, which may be summed up as being such that the person was permanently, or for a calculable period, unfit for military service in the army, or in the case of an officer or noncommissioned officer, from service in training or office work.

But besides this direct repatriation of totally incapacitated persons, many prisoners were sent to Switzerland or Holland.

In the spring of 1916, an agreement was made with the German and Swiss Governments by which prisoners whose disabilities fell within an agreed schedule but were not sufficient to justify direct repatriation should be transferred to Swiss custody.

They were selected by mixed traveling boards composed of Swiss medical men and medical officers of the captor State. Those selected were then examined by a Control Board, whose decision was final.

After the Conference at The Hague in 1917, these traveling boards were abolished, and the first selection was made by the camp medical officer, an arrangement subsequently modified at the 1918 meeting.

The guiding principles for internment in Switzerland were stated in 1917 as follows:—

"The following shall be interned:—(1) Sick and wounded whose recovery may be anticipated within a year, and whose cure will be more speedily and surely brought about by the facilities obtainable in Switzerland than by a prolongation of imprisonment. (2) Prisoners of war whose health, in the opinion of the medical authorities, appears to be seriously menaced either physically or mentally by the prolongation of captivity, and who would probably be saved from this danger by internment in Switzerland."

If the person's disabilities increased to bring him within the category entitled to direct repatriation, he was to be sent home.

Gymnastics by British Prisoners, Göttingen. In The Prison Camps of Germany, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 196cda9f51

In 1917, the Netherlands Government offered to receive all 16,000 persons, British and German, divided into three categories: (1) invalid combatants (7,500); (2) officers and non-commissioned officers who had been in captivity for 18 months (6,500); and (3) invalid civilians (2,000).

This offer formed the basis of the agreement between the British and German Governments at The Hague in June 1917. By that agreement, the schedule of disabilities for the invalids was the same as in Switzerland, except that the British Government insisted, with Switzerland's assent, that tuberculous patients should go to that country.

Much resentment was felt as a consequence of this agreement's benefits. But the British delegates were powerless. Every attempt to Induce the German delegates to agree to their inclusion was in vain.

The provisions of the agreement reached in 1917 were largely extended at a further meeting in 1918. By this, all warrant and non-commissioned officers, as well as men who had been prisoners of war for more than 18 months, should, with exceptions, be repatriated, head for head and rank for rank.

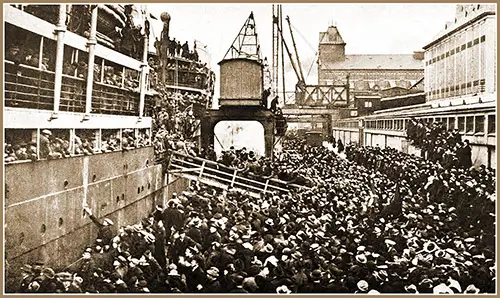

Returning British POWs About to Leave the Free Port of Copenhagen, January 1919. Enthusiastic Danes Wishing Them Good Speed. The Copenhagen Free Port, 1923. | GGA Image ID # 1d47c3ef76

Bibliography

"Prisoners of War," in The Encyclopædia Britannica the New Volumes Constituting, in Combination with the Twenty-Nine Volumes of the Eleventh Edition, the Twelfth Edition of That Work, and Also Supplying a New, Distinctive, and Independent Library of Reference Dealing with Events and Developments of the Period 1910 to 1921 Inclusive the Third of the New Volumes Volume XXXII Pacific Ocean Islands to Zuloaga, New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1922, pp. 154-158.

Conrad Hoffman, In The Prison Camps of Germany: A Narrative of "Y" Service among Prisoners of War, New York: Association Press, 1920.

💡 Why This Page is Valuable:

✔ Rare & Personal Document – King George V’s letter is a unique primary source, showing the monarchy’s role in boosting morale.

✔ Insight into POW Life – Offers detailed descriptions of conditions in German prison camps, including food shortages, punishments, and medical care.

✔ Emotional & Historical Impact – Highlights the joy and relief of soldiers returning home after enduring immense hardships.

✔ Excellent Resource for Teachers & Students – Ideal for lessons on wartime captivity, diplomacy, and humanitarian efforts.

✔ A Must-Read for Genealogists & Historians – A valuable artifact for those researching POW relatives or studying wartime treatment of soldiers.

🔹 This collection brings to life the experiences of British POWs, from suffering in captivity to the long-awaited moment of freedom, with King George’s words serving as a beacon of hope.

📜 The Letter: King George V’s Message to Released POWs

🖋️ Transcription of the King George V Letter (1918)

📍 From Buckingham Palace, 1918

"The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries and hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

"During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant officers and men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

"We are thankful that this longed-for day has arrived and that back in the old country, you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home and to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return."

/s/ George R. I.

🔍 Meaning of “George R.I.”:

"R.I." stands for "Rex Imperator" (King and Emperor), signifying the King's role as sovereign of Britain and its empire.

🔹 Why This Letter Matters:

🔹 A rare document that symbolizes the relief and joy of returning soldiers.

🔹 Reinforces Britain’s commitment to its troops, even in captivity.

🔹 Shows how monarchical diplomacy played a role in wartime morale.

📸 Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

This page includes historically significant images from In The Prison Camps of Germany (1920) that provide first-hand visual evidence of POW experiences.

📌 📜 King George V’s Letter (GGA Image ID # 20d82fd657)

🔹 A priceless artifact that was personally received by released British POWs.

📌 ✉️ The Envelope Containing the King’s Letter

🔹 Demonstrates how the letter was officially presented to each soldier, making it a cherished keepsake.

📌 🍞 American Supplies Ready for POWs at Rastatt (GGA Image ID # 19669f4c6e)

🔹 Highlights the critical role of humanitarian aid in sustaining prisoners of war.

📌 🏠 View Inside a Barracks at Göttingen (GGA Image ID # 196883fa23)

🔹 Provides a rare glimpse into the harsh living conditions in German prison camps.

📌 🕊️ Returning British POWs in Copenhagen (GGA Image ID # 1d47c3ef76)

🔹 A heartwarming image showing freed British soldiers being greeted by well-wishers.

🔹 Why These Images Matter:

🔹 They provide tangible proof of POW conditions and their treatment.

🔹 They connect readers emotionally to the joy and suffering of soldiers.

🔹 They are invaluable resources for students, genealogists, and historians studying WWI captivity.

🎯 Relevance for Different Audiences

📌 🧑🏫 For Teachers & Students:

✔ A compelling primary source to study wartime captivity and post-war reintegration.

✔ Provides a personal, emotional connection to WWI soldiers' experiences.

✔ Perfect for class discussions on diplomacy, humanitarian aid, and monarchy in wartime.

📌 📚 For Historians & Military Researchers:

✔ Offers insight into POW treatment and conditions in German camps.

✔ Sheds light on Britain’s efforts to support and welcome back its troops.

✔ Helps understand the role of King George V in fostering morale and unity.

📌 🧬 For Genealogists & Family Historians:

✔ If a family member was a British POW in WWI, they may have received this exact letter.

✔ Provides context for researching wartime military records and prisoner repatriation.

✔ Helps connect personal family stories to broader historical events.

🌟 Final Thoughts: A Moving Tribute to WWI POWs

📌 This page is a powerful, deeply emotional look at the experiences of British POWs during World War I.

📌 King George V’s letter is more than just a historical document—it is a symbol of resilience, survival, and national gratitude.

📌 The detailed account of POW treatment in Germany makes this an invaluable educational resource.

🌍 This is not just a letter—it is a reminder of the sacrifices made by soldiers, the hardships endured by POWs, and the relief that freedom finally brought. 🇬🇧✉️