The Armistice - A Story for Homeward Bound Americans - 1919

On November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed, the enemy had capitulated: the war was won. When the Americans had fought the Hun with a will to beat him or die, the days were followed by months of waiting.

During this period, 6,000 officers and soldiers were able to follow courses at the French universities, while 10,000 attended the improvised American University of Beaune.

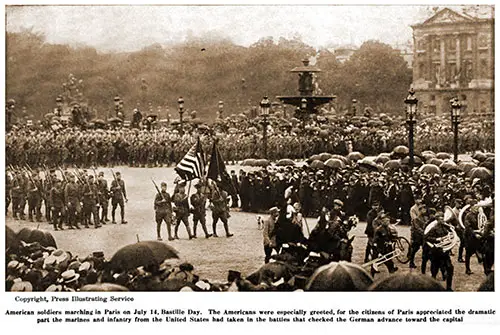

American Soldiers Marching in Paris on July 14, Bastille Day, the American Were Especially Greeted for the Citizens of Paris Appreciated the Dramatic Part of the Marines and Infantry from the United States Had Taken in the Battles That Checked the German Advance toward the Capital. Photo © Press Illustrating Service. The Story of the Great War, Volume XIV, 1919. GGA Image ID # 180a8e98ef

All the A E. F. men had an opportunity to study and become better acquainted with the French people. France now asks them, in judging her, not to forget certain fundamental truths regarding the difficulties with which she has always had to contend and the place she holds among the world's nations.

Forty million people live in France, which covers an area smaller than that of the State of Texas. Competition consequently is intense.

The Frenchman who wants to succeed must-have, though it takes years to procure it, technical training and instruction in whatever branch of an industry he intends to make his specialty.

On the other hand, because of her natural riches — greater than those of any country in Europe except Russia — France has been invaded by all of her neighbors since the beginning of her history.

In order to meet this constant menace of aggression, all young Frenchmen at the age of twenty have been obliged to leave their work and to spend a period varying from two to seven years in preparing to be soldiers at a pay of one cent a day to themselves and a cost to the government of hundreds of millions a year.

The Stale indeed spends far more on public instruction and on the upkeep of the army and the navy than on commerce and industry.

How much would such a situation affect the mentality of the Americans, the prosperity of the United States?

It determines the French people's character in their business dealings and in their choice of an occupation. Two out of every five of the inhabitants of France have something put away in the savings bank.

In 1913, all these contributions, which include small accounts given as school prizes to children, amounted to over one thousand million dollars, or an average of about $30 a head.

At the same time, the individual proprietors who own a piece of land, or a house, or both, number eight million.

This thrifty state of affairs is the result of the cautious manner in which the French people face existence: they are ready always for a possibly long period of war.

Recent history has proved the wisdom of their forethought. Following the wholly unexpected invasion of the Germans in 1914, at a moment when the French had never been more pacific, more democratic in their national sentiment, the first war loan was over-subscribed forty times.

The last budget called for in October 1918, after an enemy occupation which had endured for every four years, brought six thousand million dollars, or an average of $152 per inhabitant.

In 1871, when the Franco-Prussian conflict had drawn to a close, the Germans, hoping to crush the French, exacted from them an indemnity of one thousand million dollars.

They were at the end of a campaign during which Paris had been besieged for one hundred and thirty-one days before capitulating, and which had been followed by a civil uprising.

They had changed their form of government from an empire to a republic during the war, and they were beaten. Yet they paid the indemnity out of their personal economies, in seven months' time.

Thus, it is a national necessity for the French to prefer security to risk. Great numbers of Frenchmen become government employees simply because, though poorly paid, they receive a small pension for life at the end of twenty-five years of service.

Financiers, on the other hand, are scarce. Credit is little practiced. The Banque de France, which has 500 branches throughout the country, has only 15,000 depositors who use a checkbook. The Credit Lyonnais counts 155,000 depositors, who draw checks to an average of only $ 1,200 a year.

The fact that for fifty-two months, a violent war was actually raging on French soil has somewhat emphasized this frugal attitude about money. It has led to a slight misunderstanding in the dealings with foreigners.

A better knowledge of the reasons for so close a reckoning of the pennies should help to dispel any unpleasant memories.

In France, millions of French soldiers and millions of more overseas troops, English, Irish, Scotch, Indians, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Serbians, Russians in the beginning, and Americans later on, were concentrated in a relatively limited area.

There was also a constant stream of refugees pouring into France's free part from Belgium, from Serbia's invaded districts.

In the meantime, 8,000,000 Frenchmen had been mobilized and taken from their regular work for national defense, military and industrial. All these successive occurrences made prices go up, as inevitably as a balloon's inflation causes it to rise.

The increase in the United States calculated on forty-five different food and industrial products amounted, in the first six months of 1918, to 210% on the former cost, while in France it soared to 384% on food, and to 434% on manufactured materials.

This, you will say, is legitimate. What you object to is not the temporary increase in the value of things, but the overcharge made, especially to American soldiers.

The same was the case in 1917 when the first large training camps were established in the United States.

Considered retrospectively, these commercial impositions lose their significance. You do not care now what price Lafayette and the French Expeditionary Forces paid for chickens in 1776. You remember only that these men valued an ideal more than life.

"Liberty or Death" were the words which appeared on their ragged shirts as they marched bare-fool through the snow. Their spirit, ever-living, impelled you to take part in this war of principle, which because of your very disinterestedness, you have carried on to victory.

The French Woman

A country is as great as its women. The American girl, the citizen of a young, free-born people, unhampered by convention, generally seeks an independent line of action that develops her personality and surely furthered humanity's progress.

The woman of France, child of an older civilization, limits her influence to the family circle. She takes no direct share in public affairs; she is always part of a group whose first duty is the lending of mutual assistance.

The recognized purpose of existence for the French girl is that she should become a "wife and the mother of a citizen". All her short youth, therefore, she is preparing for the great adventure of life — marriage, which determines all worldly activity.

When the supreme moment arrives for choosing a life's companion, it is not the future bride herself but the older people who "arrange" the marriage. In this union, they recognize the culmination of a destiny.

They consider the natural aptitudes and tastes of those most intimately concerned their family ties, health, wealth, and social position.

So wise and practical, all of these matters might not be reflected upon if the girl were left to follow her own fancy. So, wherever she appears, she is always accompanied by an older person.

She may not go to a lecture, nor even to church alone, much less may she take her pleasures unattended.

Whatever the occasion, some relative is always present in whose mind one thought dominates — her charge's future happiness as a married woman.

Thus, the object of limiting the woman's independence is not to place her in an inferior position but to produce harmony in the family. In this deliberate association of two human beings with the hope of founding a home, the question of money is very naturally considered.

At the time of marriage, a contract is drawn up: just as in business, both parties concerned assume their share of responsibility.

This common budget established by both is administered by the husband; however insignificant it may be, the fortune contributed by the woman is in the form of a dowry or dot which her father constitutes for her, as a token of material protection in return for her filial submission.

All these logical restrictions do not provoke the French woman. On the contrary, it would seem as though, having put money into this human enterprise, she was determined to make a success of it.

She never seeks a social position which might separate her from her husband: she works by his side, in the Fields, or in the city.

She makes his store her parlor, his friends her own, his interests, and her ambitions one. Her joy is in her children and in the unity of her household.

Because of this absorption of the French woman in her family, foreigners have always found it difficult to become acquainted with her or penetrate the group she is the sou!.

You soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces, have had an unusual opportunity, not to make friends as freely as in America, or to enjoy the comradeship which in France is unknown, but to see and study the French woman at the most critical moment of her history.

During this war, the very homes to which she has given her life have been attacked and sullied by an unscrupulous enemy.

She has appeared to you as more than worthy of the burden laid upon her shoulders.

You have found her laborious, uncomplaining. Her abnegation has commanded your respect. You have seen her work with a sacred unity of purpose to keep up the courage and relieve the combatants' sufferings.

You have been amazed to note that with a broken heart and empty arms, she could struggle on to save others, forgetful of self-determined above all that her country should triumph.

Through all her trials and in her desolation, you have not heard her speak of sacrifice. Indeed, what has appealed to you most has been her grace in affliction, and at all times, her human tenderness.

Suppose the poilus won the battle of the Marne. In that case, if at Verdun, they would not let the Germans pass, it is because behind the line they were sustained by their obscure and glorious allies: the women of France. With toil and prayer, they helped to win the war.

B. Van Vorst, "To The Homeward Bound Americans: In The Battles of the Great War," University of Virginia, 1919. Pamphlet included in "European War 1917-1818 Pamphlets, Vol. 67.