How Immigration Is Stimulated (1906)

The RMS Ivernia, a Transatlantic Ocean Liner Operated by the Cunard Line, Was Launched in 1899 and Entered Service in 1900. By Circa 1906, the Vessel Had Accommodations for Approximately: 200 First-Class Passengers, 200 Second-Class Passengers, and 2,350 Third-Class (Steerage) Passengers. This Configuration Reflects Its Primary Role As an Immigrant Transport Ship, Catering Mainly to Steerage Passengers Traveling From Europe to North America. the Ivernia Frequently Operated Routes Between Liverpool and Boston, With Stops at Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland. Cunard Daily Bulletin, Ivernia Edition, 28 June 1905. | GGA Image ID # 21ed05ac79

As the stately Cunard steamer Ivernia, one bright morning in early March, made her way slowly up the harbor toward the famous old Charlestown dockyards at Boston, the most indifferent observer could not have failed to note a remarkable transformation in her appearance.

Against the bright white background of her figure, a succession of brilliant colors reasonably kaleidoscopic under the play of sunshine and shadow emerged.

There were patches of red, green, and yellow, with a liberal admixture of blue, scarlet, and crimson here and there. It was as if, by some strange magic, the steamer's expansive decks were being transformed before one's very eyes into gigantic flower gardens. The illusion, however, was soon dispelled.

As the good ship drew within hailing distance of the wharf, her blossoming effect became capable of an easy and by no means supernatural explanation.

It was due to nothing more or less than the picturesque costumes worn by some two thousand men, women, and children who were thronging the decks in eager anticipation of the end of a long and wearisome steerage journey across seas.

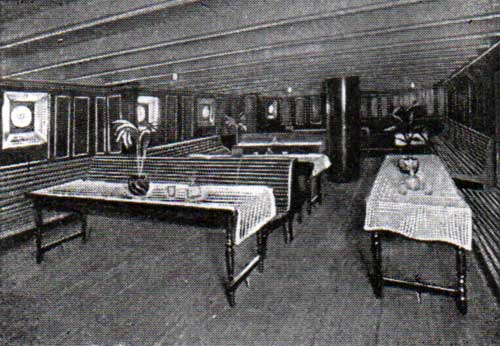

Third Class Smoking Room on the RMS Ivernia and RMS Saxonia. Story of the Cunard Line, December 1902. | GGA Image ID # 21ecec1dc2

To be exact, the Ivernia carried 1,740 passengers. Of these, 1,522 had made the trip in steerage, while 146 traveled the second cabin and only seventy-two saloon. The steerage crowd was easily the most interesting. It had been gathered from almost every corner of Europe. It comprised human beings of the most widely differentiated races, tongues, and social conditions.

Most conspicuous were the Hungarians, about six hundred in all, who, as appeared subsequently, had first assembled at the Croatian port of Fiume to sail on a Mediterranean steamer to New York, but the missing connection had been sent overland to Liverpool to take passage on the Ivernia.

Nearly half of them were women. They were in full national dress, which, in splendor of color and economy of material, gave the effect of the chorus of a comic opera. Each wore a showy scarf of scarlet, yellow, or orange on her head.

The men's costumes were scarcely less brilliant. Though classed together as Hungarians, these people spoke half a dozen languages. They could converse only through interpreters.

In addition to the Hungarians, the ship carried 390 Italians, 120 Russian Jews, about two hundred Scandinavians, 150 English and Irish, fifteen Turks, fourteen Armenians, twelve Germans, ten Finns, and five French, all of whom contributed to the mottled appearance of the crowd in their way.

For nearly an hour, the stream flowed steadily across the gangway. At the shore end, the throng was narrowed to a single file so that the United States Marine Hospital physician could look sharply for persons who bore the marks of disease or infirmity. Thence it spread again into the pen, long stairways guarded by railings led down to the inspectors' desks.

By the next day, practically all of the newcomers who had succeeded in satisfying the officials of their fitness to become residents of the country and who had any definite plans for the future were setting out to begin their new lives. About one hundred and seventy-five of the Scandinavians started on the overland trip to the great farming regions of the Northwest.

Most of the Hungarians and some of the Irish, Germans, and Armenians pushed on toward the mining districts of western Pennsylvania. Many Italians left for New York and other seaboard cities to join relatives and old friends or seek employment. A very considerable portion made no effort to get beyond Boston.

In the meantime, the Ivernia was preparing to set sail again for Europe, whence, within the space of four short weeks, she would return similarly freighted, likely enough with a steerage throng a third larger and twice as cosmopolitan.

Steerage Passengers Relaxing on Deck. | GGA Image ID # 21ed0f67d5

Only those who know the foreigner best appreciate the complexity of the influences and conditions that bring him here. They understand that rarely can it be said that any motive alone has prompted emigration in even individual ease, much less throughout a group or class.

Russian Jew tells me that he is in America because he hates the rule of the Czar but frankly admits that if he could have made a living for his family in the old home, he would have remained there the rest of his days.

His neighbor testifies that the terror inspired by the Kishinev massacre led him to migrate. Still, he also explains that he should never have considered coming to America because an uncle settled in New York a dozen years ago and prospered. An Italian ditch-digger avows that he is here only for work and wages during the summer.

His fellow townsman, however, is ambitious in giving his children the advantages they can not have in Naples but may have in Boston. So he is counting the days until his savings can bring them over and settle them in an American home.

One might continue enumerating cases from actual life, all of which serve as types and help explain why our immigrants today are so different from the masses.

The Problem of Assisted Immigration

One crucial thing that we know now but which we had only the barest intimations of a few years ago is that the volume of our annual immigration is entirely out of proportion to what the ordinary, usual influences controlling the movements of the population would make it.

In other words, it has been discovered that after all the social, economic, political, religious, and purely personal motives for immigration have been duly taken into account, we have not yet a sufficient aggregate of impelling forces to explain the remarkable increase in the numbers of our immigrants which the past few years have witnessed.

Happily, in discovering this fact, we have also unearthed its reasons. Briefly stated a considerable element in our yearly influx of aliens is the product of artificial stimulation at the hands of a variety of interests whose purposes are best served by the deliberate promotion of widespread emigration from Europe. And herein, we have found an aspect of the immigration problem no less vital than novel.

Under certain conditions, such as when Australia is to be peopled, direct emigration stimulation may be proper enough and beneficial to everybody concerned. Still, on the face of things, it has no rightful place in the transplanting of European peoples to America.

It should be, and generally is, accepted as a maxim that aliens who take up their residence in our country should do so in every case voluntarily, on their responsibility, and under no sort of external pressure.

Profiting From the Migration of Immigrants

Since, therefore, the fact has been uncovered that thousands of Europeans, especially Hungarians and Italians, are brought to America every year through the inducements held out to them by parties who expect to profit from their migration, it may be affirmed without hesitation that the phase of the immigration problem which calls for most immediate and decisive action today is the reducing of the movement to the volume it would generally sustain if fixed solely by the bona fide enterprise of the immigrants themselves.

As things now are, the first and most obvious step is to eliminate every form of artificial stimulus to immigration. This task may be attacked while we are still debating questions of admission and exclusion, urban congestion, and distribution and assimilation.

Few people realize, because few are in a position to know, how strong the mercenary influences are, which are always at work drawing men and women into the swift stream of migration who ought never to leave their old homes and would never do so under normal conditions.

This fostering of immigration for the money that there is in it is an unmitigated evil. It is such whether regarded from our standpoint or from that of the immigrant himself, and every effort made to counteract it is wisely directed.

Not long ago, a lady connected with the Associated Charities of the District of Columbia called the Immigration Bureau in Washington and reported the case of a Hungarian family, which admirably illustrates one aspect of the evil of enticed immigration.

The entire family in question, consisting of husband, wife, and five children, had once lived in Budapest, where the husband was a barber and the wife a hairdresser. Prosperity had rewarded their industry, and they had come to be far better situated than the average people of their class.

Both were happy and content. However, an agent of a steamship company called upon the husband and told him that while he was doing very nicely in Budapest, he could do twice as well in America.

The suggestion of emigration was pondered and finally acted upon. The barber left his wife and children and came to Baltimore, expecting his labor eventually to make them a home in the new world.

Finding that the wages paid by barbers in Baltimore were scarcely adequate for his support, he left the place. He went to Washington, where he got a position at ten dollars a week.

This income enabled him to send small amounts regularly to his wife, and though he was in no way enthusiastic regarding the step he had taken, he resolved to make the test of it and continued to send home letters thoughtfully concealing the real struggle he was having.

The wife, supposing that her husband realized the expectations created in their minds by the steamship agent, sold their custom and household belongings and came to Baltimore with the live children, rejoicing in the pleasant surprise she was preparing.

The surprise, however, was anything but pleasant under the circumstances. The husband, in response to the telegram giving him his first intimation of the family's arrival, hastened to Baltimore and led his loved ones back to his cheerless room in Washington.

No time was required, of course, for the wife to realize the error into which she had unwittingly fallen. In a short while, she became so hysterical from distress and homesickness that, in the opinion of the lady who reported the case, she would shortly have to be confined to some institution for the insane.

No relief could be forthcoming from the Immigration Bureau since after aliens are once legally admitted to the country, there are no means by which they can be deported.

In such a manner, one happy and prosperous European family was involved in material and mental ruin simply because a steamship agent wanted to increase his business by selling the several tickets required for the family's removal to America.

The case, with minor variations, could be duplicated scores of times in the charity records of any of our great cities. With the added feature of incapacity, disease, or degradation on the part of the immigrants thus thrown upon us, it could be paralleled unknown hundreds of times.

Three Main Sources Stimulating Immigration Today

- Transportation Companies, chiefly the great transatlantic steamship lines;

- A variegated class of European "agents" and "runners" whose relations with the steamship companies are not always easy to make out and

- Large employers and employment agencies in the United States.

In treating the subject, dealing separately with the first and second is impossible. However, they are by no means identical.

Transportation Commutes and Immigration

The incitement of emigration to the United States by interested parties is no new phenomenon. As far back as 1891, it was deemed a matter sufficiently necessary to call for legislation by Congress, and in that year, enacted a statute by which effort was made to restrict immigration to the number of those who should seek homes or employment in this country purely of their own accord.

This measure has become inadequate. In 1903, its terms were stiffened by amendments providing, among other things, that the soliciting of immigration by transportation companies or their agents, orally, or in writing or printing, should constitute a criminal offense punishable by fine, and also providing that at every port where transportation companies sell tickets to aliens, they must post the immigration laws of the United States conspicuously in the language of the country concerned.

Even this legislation, however, was only indifferently successful. The large numbers of sick, disabled, pauper, and immoral Europeans who continued to be brought to the American ports were quite enough in themselves to create a suspicion that their coming had not been due solely to their initiative.

Suspicions Europe Promoted Immigration to the U.S.

This feeling became so intense among persons acquainted with the facts that soon after Mr. Sargent took charge of the Immigration Bureau, he adopted the plan of sending an inspector through all the more important European countries to ascertain as far as possible to what extent emigration to the United States was being augmented by the activity of transportation companies and their various agents.

Mr. Marcus Braun was chosen for this mission. His meticulous work, along with that of more recent inspectors like Mr. Maurice Fishberg, is largely responsible for our understanding of the actual processes and extent of immigration in the late years, a period often referred to as the 'misted immigration' era.

Mr. Braun embarked on a meticulous investigation, sailing for Hamburg in April 1904. His journey took him up and down through Europe, covering a total distance of twenty-five thousand miles. He studied conditions in ten leading countries and at sixteen important ports with untiring diligence, leaving no stone unturned in his quest for knowledge.

Upon his return, Mr. Braun compiled a comprehensive report detailing his findings and recommendations. This report, which can be found in the Annual Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration for the year ending June 30, 1904, provides a wealth of information about immigration patterns and the role of transportation companies.

In this fascinating document, the inspector expressed the conviction that but for the activity of the transportation companies in their hunt for business, the volume of immigration into the United States would not exceed one-half of the present figures.

Are the Steamship Companies At Fault?

A state of affairs that may challenge attention is revealed here. All of the great transatlantic steamship companies, such as the Cunard, the White Star, the Hamburg-American, and the North German Lloyd, are served throughout Europe by a vast body of agents ranging in importance from the companies' representatives at leading ports like Hamburg, Liverpool, and Naples to ignorant Austrian and Italian peasants who perchance have never wandered a hundred miles from their native villages but who nevertheless, for the sake of the commissions they hope to be paid, are active in stirring up their fellows to try their fortunes in a new world.

It would be hardly correct to say that companies maintain this elaborate hierarchy, for at the most, their connection with their inferior members is only indirectly through their superiors.

The line, however, between the regularly commissioned and salaried and the practically self-constituted agents cannot be determined with any approach to accuracy.

On the face of things, the situation is this: each company maintains an authorized agency at essential points; these appoint sub-agents, who in turn enlist the services of all classes of people occupying all sorts of positions to drum up traffic for their respective lines.

But when the companies are taken to task for the abuses committed by these subagents, they promptly disclaim all connection with anyone but their general representatives and profess to be in complete ignorance of the abnormal pressure constantly being put upon the masses of Europe to migrate.

So far as they have any, the simple function of these subagents is to supply information when called upon, especially regarding sailing schedules, rates, and other details of ocean travel.

Practically, however, they have become an army of recruiting officers, influencing and enticing people with all degrees of flagrant deceitfulness to begin life anew in America—and, of course, incidentally, to take passage thither on one of their company's splendid new liners which sail on such and such a (very convenient) day, and the rates of which are so very, very low!

The village agents work under the direction of district agents, and all are stimulated to their utmost exertions by the commission that they receive when they deliver their passengers at the steamship company's docks.

"The more they get," says Mr. Braun in a letter written to the Immigration Bureau during his tour of inspection, "the easier it is to keep up the entire flow of the tide, and the interest and excitement in the movement is stimulated in every possible way where the emigration fever has obtained a good foothold.

Future Immigrants Are Easy Pickings For Steamship Agents

In northern, central, and southern Europe, there is an enormous amount of material to work on. The most remote agricultural valleys are invaded by agents with advertising matters of every description, and emigration missionaries ostensibly engaged in other business. It is one of the best organized, most energetically conducted branches of commerce worldwide."

Tickets are sold to people who have but the vaguest idea of where they are going, who lack all of the qualifications necessary for life in a strange country, and who, in many cases, are so manifestly unfit that they can not possibly be made to pass the admission examination at any American port.

Every sort of ingenuity is practiced to "patch up" persons afflicted with trachoma, favas, and other diseases so that they may succeed in getting through.

It is difficult to take responsibility for these shameful abuses. Most European countries, especially Germany, Austria, and Italy, have stringent laws against the enticing of emigration, designed, if for nothing else, to prevent the draining off of young men capable of military service. The energy with which they have sought to secure the execution of these laws must relieve them of any significant measure of blame.

The fault lies with the steamship companies and the network of agencies that provide them with passenger business. It will not go too far in condemning the companies themselves, for their guilt is susceptible to a perfectly natural, even if not wholly adequate, explanation. Besides, the fault is not all their own. The temptation to exploit immigrant travel to the utmost is undeniably strong.

Until very recently, at least, representatives of the companies admitted that steerage traffic was their primary source of income. At present, they generally claim that this is not true. However, this traffic volume has lately increased so much that it is difficult to account for the alleged fall in profits. The bitterness of the famous rate war of the summer and autumn of 1904 makes one suspicious.

In any event, it is not to be questioned that immigrant travel is still a very large item on the companies' account boots, and it is only natural that, other things being equal, these companies should desire to increase it just as a factory owner or a mine operator would want to increase his output.

As Mr. Sargent has quite rightly said, "It is useless, if not puerile, to trust that the transportation line, representing enormous investments of capital, operated for the express purpose, will not resort to every known means to secure passengers, or that persons acting as their agents in foreign countries will not do likewise to secure commissions, even if such acts involve a violation of the laws of the United States.

The former is quite natural and commendable within lawful limitations; the latter may be reasonably anticipated." The ethics of the matter lie in a particular direction. Still, practical experience teaches what may be expected.

Remedies, Existing and Proposed

It is difficult to determine the extent to which the companies are guilty of positive misconduct in this matter compared with the extent to which they are the more or less unconscious, even unwilling, victims of their self-serving European agents and "feeders."

The best evidence shows that, on the whole, the companies endeavor to comply with the law—the letter, at least, if not the spirit. They know that they are held to account for every immigrant whom they transport to our coasts.

They bring persons whom the immigrant inspectors refuse to admit. They are bound to pay for the board and lodging of such persons while in the detention pens and eventually carry them back to their homes free of charge.

If they bring persons afflicted with contagious diseases and it can be shown that the disease existed at the time of embarkation and might have been detected by a competent physician, they are subject to a fine of one hundred dollars for every such person transported and must supply free board, lodging, and return passage.

These requirements unquestionably operate as a valuable check upon companies' zeal for immigration business, and the rigid enforcement of legislation of this character is one way of ameliorating the assisted immigration evil in the future.

When steamship officials come to understand a little more clearly that transporting diseased, impoverished, and defective persons has become a source of positive financial loss through fines and refusals to admit at the immigration ports, they will not be long in finding a way to protect themselves against the impositions of their overzealous employees and self-appointed servitors.

Already, the stricter enforcement of the law by our immigration inspectors within the past two or three years has had a noticeable effect, and it is easy to see that the steamship companies themselves have begun to thoroughly screen the people who apply to their European agencies for tickets to America.

For example, the worst Hungarians are usually in such a physical and financial condition that American inspectors would almost certainly reject them; hence, the companies shield themselves against probable loss by carrying these people to England, where immigrant regulations are not so rigid.

But while, as a rule, it is the most ignorant, most credulous, and least desirable elements of the European peasantry that are chiefly appealed to by the immigration promoters, it is nevertheless true that the efforts of these men induce the removal to America of large numbers of people who cannot be denied admission under any reasonable exclusion regulations.

The problem must be dealt with in Europe as well as in America. It is essentially international in character and can never be solved completely until the nations concerned take it up together and work out a common program of action.

Steps Needed to Address the Immigration Problems

First of all, those nations that already have laws prohibiting the enticing of emigration must be stirred to greater vigilance and energy in their execution.

In the second place, countries like Switzerland, which have no such legislation and have, consequently, become the rendezvous of emigration agents and runners, must be brought to the point of active cooperation toward the suppression of illicit business.

Thirdly, the steamship companies, being mostly international and therefore immune from close control, should be subjected to enough pressure to keep their solicitation of business within legitimate bounds.

The mere arrest and conviction of a sub-agent here and there has little or no effect on the general situation. It does not involve the steamship companies in the controversy and apparently only stimulates other agents to use more adroit methods of evading the law.

In any individual case, the ticket sold to an "assisted" emigrant passes through so many hands before it reaches him. The original commission for handling the business is subdivided so often that laying a hold on the guilty party is impossible if the company itself is eliminated.

Finally, inspection work must be transferred as far as possible from American to European ports. Although no active steps have yet been taken in this direction, it is well known that this is to be the policy of the Immigration Bureau under its present management.

Our consuls in foreign countries are expected to prevent the shipment of paupers or criminals to this country. Still, in practice, this function of the consul does not mean much. His powers are too vague and general, and his time is too occupied with other things.

Adequate inspection of emigrants before embarkation can be secured only by creating a special class of officials to reside at the various European ports and devote their energies to this business alone. A plan for taking such a step is currently under consideration.

If a system of this sort is instituted, the problem of stimulated immigration can be attacked close to its roots, and the present evil may reasonably be expected to be greatly removed.

If, as President Roosevelt has recently declared in his last annual message to Congress, "the most serious obstacle we have to encounter in the effort to secure a proper regulation of the immigration to these shores arises from the determined opposition of the foreign steamship lines, who have no interest whatever in the matter save to increase the returns on their capital by carrying masses of immigrants hither in the steerage quarters of their ships."

The most promising means of outwitting those who would prey upon our national well-being for their pecuniary interests is to make a rigid examination of all our prospective immigrants and weed out the undesirable before they have had a chance to pay their precious lint, roubles, and kroner into the rapacious treasuries of the transportation companies.

Ogg, Frederic Austin, "How Immigration Is Stimulated," in The World Today, Volume X, Number 4, April 1906.

How Immigration Is Stimulated (1906)

A Critical Examination of Mass Migration and Its Hidden Influences

For teachers, students, genealogists, family historians, and immigration researchers, this insightful article offers a compelling exploration of how immigration to the United States was artificially stimulated in the early 20th century. Through a detailed analysis of steamship companies, labor recruiters, and transatlantic migration trends, it exposes the forces that fueled one of the most significant waves of immigration in American history.

Why This Article is Essential for Understanding Immigration History:

- Revealing the Hidden Forces Behind Immigration – This article uncovers how transatlantic steamship companies, labor recruiters, and intermediaries encouraged emigration for financial gain, often misleading prospective immigrants with false promises of success in America.

- The Role of Steamship Companies in Mass Migration – Learn how companies like Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-America, and North German Lloyd actively promoted migration through vast networks of agents, who worked in even the most remote European villages to recruit passengers.

- The Realities of the Immigrant Journey – The detailed account of the RMS Ivernia’s arrival in Boston paints a vivid picture of the diverse backgrounds, expectations, and challenges faced by immigrants from Hungary, Italy, Russia, Scandinavia, and beyond.

- Assisted Immigration and Its Consequences – Discover how many immigrants were deceived into coming to America under the influence of recruiters, only to find themselves struggling in unfamiliar cities with no means of support.

- Exploitation of Labor and Vulnerable Populations – Large-scale employers used immigration as a tool to acquire cheap labor, leading to overcrowded cities, poor working conditions, and fierce labor competition.

- The Impact on Immigration Policy – This article examines the early U.S. efforts to regulate and restrict manipulated immigration, leading to stricter inspections, deportations, and policy shifts in the early 20th century.

- Firsthand Accounts of Immigrant Hardships – The story of a Hungarian barber who uprooted his family based on misleading promises highlights the devastating personal consequences of artificially stimulated immigration.

Who Should Read This Article?

- Teachers & Students – Ideal for classroom discussions on immigration patterns, labor history, and transatlantic migration.

- Genealogists & Family Historians – Provides valuable context for understanding why ancestors may have been encouraged—or pressured—to emigrate.

- Historians & Policy Researchers – A crucial resource for those studying immigration laws, labor exploitation, and the role of corporate interests in migration trends.

This article challenges traditional narratives of immigration as purely voluntary, exposing the economic, corporate, and political forces that shaped the journeys of millions. Dive into this in-depth analysis to uncover the hidden mechanisms that influenced your ancestors' migration and helped shape America’s immigration history.