The Arrival and Transit of Immigrants Arriving in Boston

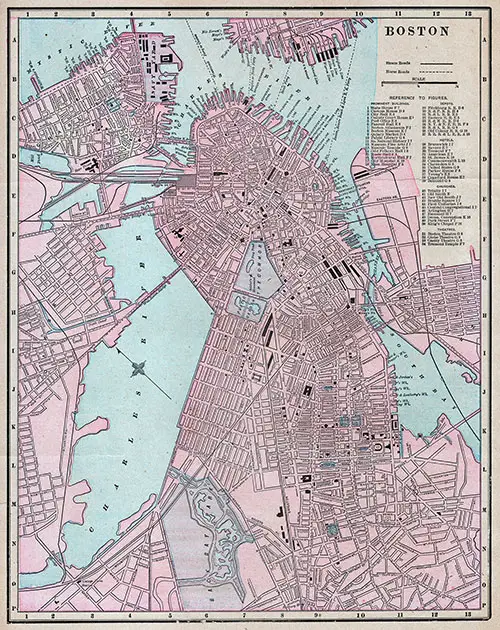

Map of Boston Harbor, 1899. GGA Image ID # 147b34a5ad

The development of the port of Boston will increase the need of protecting the immigrant on his arrival and during his transit through Massachusetts, for with the increase in the number of steamers arriving the number of immigrants entering at Boston will also significantly increase.

It is therefore highly critical for the Commonwealth to consider whether it is appropriately meeting the human responsibility which comes with the development of its commercial policy.

As the admission of immigrants is a federal matter, the conditions surrounding their release are also mainly under federal control. But wherever the United States authority or supervision stops, the responsibility of the State begins, so it is necessary to determine the extent to which the federal government is providing adequate care and protection for those who arrive at the port of Boston, or who arrive at some other port and come to Massachusetts.

THE UNITED STATES IMMIGRATION STATION

The United States Immigration Station in Boston is on Long Wharf at the foot of State Street. Here immigrants who fail to pass primary inspection on the docks, and who are held for observation of their physical or mental condition, are detained until their friends or relatives can be heard from, or until the Secretary of Labor has decided an appeal which has been taken from the decision of the local Commissioner of Immigration as to their eligibility for admission into the United States.

These detention quarters are disgracefully inadequate and would be extremely dangerous in the event of a fire. Two appropriations for a new station have been made, - one of $150,000 in 1910, and another of $125,000 in 1911.

Of this $275,000, $64,000 has been spent in the purchase of a site in East Boston, but nothing more has been done. Given the shocking conditions prevailing on Long Wharf, this extended administrative inactivity is wholly inexcusable.

CONDITIONS ON THE DOCKS

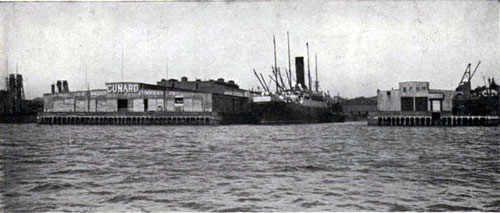

Colorized Postcard of the Commonwealth Pier in Boston, Postally Used 4 August 1919. GGA Image ID # 147b6b24d9

Unfortunately, the inspection of immigrants by the federal government, to determine whether or not they shall be admitted, is not conducted at any one place in Boston as it is at Ellis Island.

On the East Boston, Charlestown and Commonwealth (South Boston) docks, a room is equipped for the inspection of the immigrants, and this room is entirely under the control of the United States immigration officials.

Next, it is a general waiting-room for third-class and steerage passengers. From the inspecting room the public is excluded, in order that there may be no possible coaching of the immigrants for their examination.

Admission to the waiting room is denied all except those who hold custom passes. In so far, then, as the public is excluded from the docks in Boston, it is in the interest of the enforcement of the immigration and the tariff regulations.

At Ellis Island, the protection of the immigrant is also considered. In Boston, after the immigrant has passed inspection, he is regarded as needing assistance and direction no more than the cabin passengers.

That very much more is necessary for the bewildered immigrant there can be no question. The waiting room in which he finds himself when admitted is a scene of hopeless confusion. Those who are to remain in Boston are not separated from those who are going farther.

Certain favored immigrant bankers and agents of transfer companies mingle with the crowd and add to the confusion. There is no uniform method of handling the baggage, and those who bring orders for railroad tickets to their destination, and those who must purchase them here, are not systematically passed along to the different officials with whom they must deal.

MORE SUPERVISION OF THE RELEASE OF THOSE DESTINED TO BOSTON NECESSARY

Some of the immigrants who are going to friends in or near Boston - the very young or those who have suspicious addresses - are detained by the United States officials until their friends have been notified to call for them, but the vast majority are released after primary inspection.

As soon as their baggage has been examined, the average immigrant is free to leave. Here is where his confusion begins. He has no way of knowing whether or not his friends and relatives are waiting for him in the crowd outside the docks, unless it happens that a representative of one of the private societies offers to go through the crowd for him, calling out the name of the person whom he expects. The helplessness of the young immigrant woman who plunges into this crowd alone can be appreciated.

The employees of transfer companies also solicit patronage in the third-class waiting-room and occasionally obtain money from the immigrants on all sorts of pretenses.

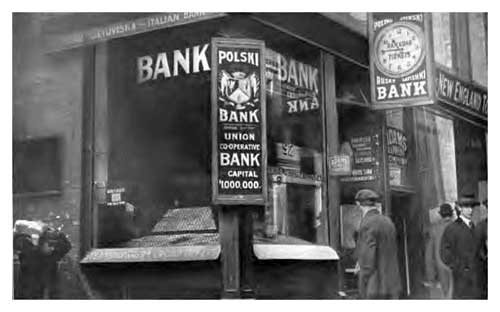

Representatives of some of the immigrant banks are admitted to the docks, and as the immigrants come out of the inspection room take in charge not only those whose prepaid tickets were purchased at the "bank" they represent but others also.

These they take first to the bank and then to their relatives or friends. Some of these bankers claim that they make no charge for taking an immigrant from the dock to his address, but evidence to the contrary was found. For example, a Polish girl arrived on the "Hanover" at the Commonwealth Pier in November.

She was going to a South Boston address, but was taken by an immigrant banker to his establishment on Salem Street, in the North End, charged 75 cents, and then placed on a street car and left to find the South Boston address alone.

In this case, the girl brought an address other than that of the banker who took her from the dock, but many are admitted who have only a bank or steamship agency address.

These immigrant bankers and ticket agents, for obvious commercial reasons, encourage those in America who are sending for their relatives or friends to give the address of the bank.

This practice should be discouraged by the government, an investigation shows that the banker seldom knows what has become of girls who gave his address on the manifest sheets.

An investigator for the commission, together with two men and two women immigrants, was put in a cab by another of the immigrant bankers on one of the docks.

Each of these five persons paid the banker $1 before they started, and besides this, the driver demanded 50 cents from each when they reached their destination. The legal fare was 50 cents in each case.

The driver could not find the friends of the investigator at the address he showed, and with a complete absence of responsibility left the "immigrant" to shift for himself in the crowd that gathered around him.

This situation has several ugly aspects. The privileges given the bankers on the dock may, as in this case, help to build up the control which is so many times abused; illegal fares are collected and, most serious of all, a person supposed to be entirely ignorant of the language and the city, may be abandoned when friends are not to be found. Failure to find the relative or friend is a widespread occurrence.

Many immigrants who arrive bring incorrect addresses. Polish girls frequently come with what proves to be an old or wrong address of someone from their village.

For example, the records at the office of the Commissioner of Immigration show that a Polish girl of eighteen arrived on the "Cleveland" in November, and was going to her father at 51 Beckford Street, Roxbury.

An investigation, later on, showed that the man was unknown at that address and the girl had never been heard of.

A Lithuanian girl, twenty-one years of age, who arrived on the "Laconia" during the same month, according to the records, was going to her brother at 164 St. Clair Street, Boston.

When an effort was made, by an investigator for the commission, to verify her arrival, it was discovered that there is no such street in Boston, and although St. Charles and several other streets were tried, the girl could not be found.

Both of these girls may have been met at the dock and taken to the correct address of their relatives, but the official records do not show, as they should, whether this was or was, not the case. If a girl's friends cannot be found, a cabman is probably not the one who should be trusted to arrange for their care.

The drivers employed by the bankers and transfer companies on the dock are picked up when a boat arrives and employed at a fixed price, usually 20 or 25 cents an hour.

It would not be surprising if these men had no interest in the delivery of the immigrant, beyond the day's wages and the illegal fee, which they may be able to collect. No record of the names or addresses of the immigrants is kept by the immigrant banker or transfer company, so there is no check on the drivers.

Immigrants whose friends cannot be traced are sometimes brought to one of the agencies working among immigrants. The superintendent says she never raises the question as to the fares charged, as this might mean that the girls would not be brought to her in the future, and she thinks their moral safety more important than the prevention of financial exploitation.

With the proper supervision of the release of the immigrants, moral and financial exploitation could both be avoided. Only by official control of this situation can adequate protection be given.

Those who are going beyond Boston should be separated from those who are to remain. Representatives of bankers and transfer companies should be kept out of the crowd.

Those who call for immigrants should furnish some identification, and their names and addresses should be recorded. The federal immigration authorities should keep a record of the immigrants who are delivered by cabmen, together with the name and number of the cabmen.

These cabmen should be required to report back any addresses at which immigrants were left other than the ones recorded when they were taken from the dock.

The keeping of this record would in itself prevent many of the practices which are now so general. If an investigator representing, for instance, the proposed Board of Immigration occasionally checked up these cabmen, very much greater protection than is currently possible could be given at a minimal cost.

THE WORK OF PRIVATE SOCIETIES ON THE DOCKS

The Commissioner of Immigration for Boston reported that representatives of the following societies are authorized to work among the immigrants at the various docks when passenger steamships arrive: the North American Civic League for Immigrants, the Immigrants' Home of the Women's Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, the Young Women's Christian Association, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the Italian Immigrant Aid Society.

In addition to these, the investigator for the commission found the following: the Young Men's Christian Association, the Council of Jewish Women, the American Tract Society, the Swedish Lutheran Immigration and Seamen's Home, a Norwegian organization, the Bethany Danish Lutheran Church, the Polish Immigration Society and the Massachusetts Bible Society.

Some of these agencies do not meet many boats, and a few of them do very little intelligent work when they are on the docks. Others are doing everything that a private agency can do to give the assistance of which these people are so much in need.

Some of the work which they are undertaking to do can be done effectively only by the federal government, because of agents of private societies, however intelligent and resourceful, are without the authority which is necessary to give adequate protection.

It often happens during the busy seasons that there are more than a thousand immigrants on one steamer, and occasionally more than one steamer arrives in a day.

With no separation of those who are going beyond Boston, there is such confusion that the agents of societies, no matter how competent they may be, cannot be sure of discovering those who are most in need of help.

The private society has, however, an important field of service which can never be covered by the government. For example, the relatives and friends of an immigrant girl often cannot be discovered because of any number of things which may have happened to them since the girl last heard from them.

The government ought not to release her unless someone is willing to undertake to care for her and assist her in finding work. Because the girl is eager to remain, is healthy and ready to work, a private agency offers to do these things for her. This is a serious responsibility which the government grants and the private society accepts.

It is therefore extremely important that agencies should not be admitted to the docks or detention quarters, and that immigrants should not be released to them, unless these agencies are investigated, not once but frequently by the State Board of Charities, or by the proposed State Board of Immigration whose judgment the Commissioner of Immigration could also consult. There is a great opportunity for exploitation should the agent of a society prove unscrupulous.

This is not so likely to happen as that the work of some of the agencies may result in harm because, although well meant, it is unintelligently done. Those agencies which do not investigate places where girls are placed, which have no follow-up system, but simply trust that everything has worked out as well as they hoped it would, should not be permitted to do this work. The investigations of the United States Immigration Commission showed that careful supervision of these societies is necessary. Such supervision will be welcomed by societies with modern standards for social work.

IMMIGRANTS WHO ARE GOING TO POINTS OUTSIDE OF BOSTON OR MASSACHUSETTS

For the immigrant who is going beyond Boston, there are special difficulties in connection with his railroad tickets, his baggage and his transfer to the depot.

PURCHASE OF RAILROAD TICKETS

Many immigrants come with orders for railroad tickets to their destination, which they have purchased abroad or which were sent them from the United States. These orders must receive the O.K. of an official of the steamship company, and must then be exchanged for a ticket at the railroad ticket office on the dock.

As there is no system of lining up the immigrants and having them pass by both windows, or of inspecting their tickets before they leave, many mistakes are made.

For example, a Pole who went to Michigan wrote to the commission complaining that although his ticket had been signed and stamped on the dock, and he had been told that no additional payment was necessary, he had been required to pay $11 to the conductor on the train.

He had not understood that his order should have been exchanged on the dock for a ticket and believed he had been cheated. The steamship company, of course, refunded the money when the commission returned the order, but the Pole had been ignorant of the fact that a refund could be secured. Again and again, the investigators for the commission found immigrants at the South Station who had had a similar experience.

LOST BAGGAGE

There is also much unnecessary confusion and delay on account of baggage. The immigrant who has a through ticket is transferred from the dock to the railroad station free of charge, and is allowed to take one piece of baggage without payment.

Those who are going on the Boston & Maine or the Boston & Albany can check their baggage through from the docks. Those who are going on the New York, New Haven & Hartford are usually given claim checks which must be exchanged for baggage checks at the depot. As the immigrant is entirely ignorant of these differences, this leads to great confusion at the South Station.

Many complaints were made at Fall River of the frequent loss of baggage, and also of the fact that the transfer company sent by express baggage which might have been checked.

One immigrant complained that he paid on the dock in Boston what he supposed was the railway baggage charge, a sum which was much more than the legal rate for taking the baggage to the station and that when the baggage finally reached him the express charges had still to be paid.

The fact that payment is commonly made to railroads in Europe for carrying baggage makes it easy for the transfer agent, should he be dishonest, to defraud immigrants in this way. All of this could easily be controlled if the federal immigration authorities supervised this matter.

TELEGRAMS TO FRIENDS

The immigrant who is going beyond Boston is and should be, encouraged to advise his relatives or friends of his coming. If he is detained, and the assistance of his friends is necessary, accurate information of the cause of detention should be sent at once.

When he presents himself at the telegraph stand on the dock, he has only the name and address to which he wants a telegram sent. He cannot speak to the operator and would not know what to say if he could, for the route over which he is to travel is not selected by him, but is determined by "friendly agreement" among the railroads and steamship companies.

The time of his departure, and whether he goes on a special immigrant train or by one of the regular trains, he has no means of knowing. His ignorance and complete dependence make it so easy to defraud him that protection is always necessary.

The whole relation of the immigrant to the telegraph agent is so different from that of the regular patron, that special regulations are needed.

At Ellis Island, because of the enormously greater numbers that arrive, these difficulties have been more apparent, and a good many safeguards have been worked out.

All the telegrams regarding detention for causes which may mean the deportation of an immigrant are regarded as official and are signed by the Commissioner of Immigration. In Boston, these telegrams are sent out by the steamship companies.

For other telegrams the telegraph company has for years furnished its operators and canvassers at Ellis Island with printed forms on which only the name of the person, the railroad and the hour of departure have to be written in.

A receipt showing the name and address of the person to whom the telegram is sent, and the amount charged, is given every immigrant who sends a message.

The commission found none of these precautions taken in Boston, and that on both the Cunard and the White Star docks the immigrants were frequently overcharged and inaccurate telegrams often sent.

This was therefore taken up with the management of the telegraph company, and it was agreed that a system similar to that used at Ellis Island should be adopted.

FOOD ON THE DOCKS

Most of the immigrants who are going to points beyond Boston buy at the lunch counter on the docks one meal and a lunch for the journey. Investigation showed that hot coffee or hot food of any kind cannot usually be purchased; that the food which is sold is poor in quality and very high priced.

One man who has the contract to furnish food' for those immigrants who are detained for special inquiry at Long Wharf runs the lunch counters at the Cunard and the White Star docks.

At his stands, a bottle of sarsaparilla which costs 10 cents in the city sells for 25 cents. Canned meat sells for 25 cents; the same package can be purchased at grocery stores for 10 cents. A 5-cent loaf of bread, very poor in quality and often old, he sells for 10 cents.

On the Hamburg-American docks, a lunch bag which was being sold the immigrant for 50 cents was found to contain a half loaf of bread, a very curious looking jelly roll, a small piece of salami sausage and five small apples.

The lunch box sold at Ellis Island for the same price contains one pound of bread, one-half pound of sausage, five sandwiches, one carton of crackers and three pies.

While the higher numbers handled at Ellis Island make it possible to buy to better advantage, there can be no excuse for the excessively high rate and poor quality of the food on the Boston docks. It would seem as if here, as at Ellis Island, this could be prevented by government control.

THE IMMIGRANTS AT THE RAILROAD STATION

Inadequate provision is now made for the protection of the immigrants at the railroad stations. For example, those who are brought from the docks to the South Station to take the afternoon train for Fall River are turned loose in one of the largest railroad stations in the world during the hour when the crowds make it most bewildering. And yet they must recheck their baggage and find their trains with only the same kind of advice and help that is given the American traveler.

The dangers at the railroad station are greater than those on the docks because the general public is not admitted to the latter. Those who arrive almost daily from New York to remain in Boston are assisted by representatives of the North American Civic League for Immigrants. But here, as on the dock, a private society is without the authority which is necessary for adequate supervision.

The same methods suggested for the supervision of those who are released at the docks should be installed by the federal immigration authorities at the Boston railway stations, and extended to other important immigrant centers.

THE JOURNEY BETWEEN BOSTON AND NEW YORK

The port of arrival in no sense determines the destination of the immigrant. Many enter the port of Boston who are destined for New York, and more who are destined for Massachusetts land at Ellis Island.

Through an agreement entered into by the steamship companies, the immigrants are sent from New York to Boston or from Boston to New York by the Sound boats.

In 1819 the first regulation of the steerage quarters of ocean vessels was made by the United States government. As early as 1847 more than two tiers of berths were prohibited in vessels carrying immigrants from Europe to America or from America to Europe.

The standard for ventilation, for the space required for each passenger, for cleanliness and for separate provision for the sexes has been raised by legislation from that time to this, and the present Congress will undoubtedly require further improvements.

To ensure the carrying out of the provisions of the law the boats are inspected before every sailing by United States consuls in Europe and by customs officers in the United States.

The experience with ocean steamers gave the government every reason for anticipating that, in the absence of regulation and inspection, overcrowding, unsanitary conditions and inadequate protection for the women and girls were sure to be found in the boats engaged in this interstate business, but nothing has been done to prevent these evils.

Self-interest on the part of the United States should have suggested special precaution in the protection of the morals and the health of the immigrant after he has been admitted to the United States.

But, on the contrary, although much thought has gone into the protection of the immigrant on his journey to the United States, his journey in America has gone entirely unconsidered.

The complaint was received by this commission concerning these Sound boats, of the sanitary' conditions, the treatment of the women by the crew, and the serious overcrowding of the immigrant quarters during the rush season. Investigators of the commission were therefore assigned to make the trip as immigrants.

They found the beds filthy, the ventilation incredibly inadequate and the overcrowding serious. The immigrant men were made the butt of coarse jokes, and the Polish girls were compelled to defend themselves against the advances of the crew, who freely entered the women's dormitory and tried to drag the girls into the crew's quarter.

On one boat petty graft was found to be practiced by some of the crew. These conditions were, of course, due to neglect on the part of the company, but also to even greater neglect on the part of the United States government in taking none of the precautions which experience had shown were absolutely essential in ocean travel.

In the hope of securing immediate improvement in the conditions found on these boats, the reports of the investigators of the commission were submitted to the New England Steamship Company.

The officers of the company at once replied that they had been ignorant of the existence of the conditions until the reports of the commission were received, and assured the commission that after investigation the company would either submit plans for the improvement of this service, or would abandon it, as the kind of thing the commission reported would not be tolerated. The company's investigation confirmed that of the commission and some steps were at once taken for improvement.

An arrangement was made by the company for withdrawing the boats in turn from the service so that the immigrant quarters could be rebuilt to provide outside ventilation for both men's and women's quarters, more sanitary washrooms, and complete separation of the crew's quarters from those of the immigrant.

Arrangements were made for clean linen and bedding for every trip. An immigrant steward with assistants was placed in charge of the immigrant service, and a special immigrant stewardess was assigned to the women's quarters.

After the company promised these changes, one more trip was made by the investigators for the commission, when 180 immigrants who arrived in Boston were sent to New York by way of Fall River on the "Priscilla."

Although the immigrants' quarters on this boat had not been rebuilt, conditions were much improved. The immigrant steward and stewardess seemed kind and efficient. All but three of the men were given berths by using the quarters usually reserved for soldiers.

The linen and the floors of the dormitory and washrooms were clean when the boat started. The company reported on December 22 that the steamer "Providence" had been rebuilt according to plans submitted, that the "Plymouth" and the "Chapin" were then in the repair shop being renovated and rebuilt, and that the steamer " Priscilla" would be withdrawn and similar changes made in her as soon as the "Plymouth" was back in the service.

No inspection has been made since that date. All this, if carried out, will mean enormous improvement in conditions. But legislation and continuous inspection are needed.

The three and four tier berths, although abolished on the ocean liners in 1847, are still used in this service, and the temptation to overcrowd dangerously and to lower standards during the rush season is very high.

While it is believed that the protection and supervision of the immigrant, from the time of his arrival until he reaches his destination, can be more effectively handled by the United States government than by the State, much could be done, as in this instance, if there were a State Board of Immigration which was authorized to make inspections and to suggest the improvements which were found necessary.

INSPECTORS ON IMMIGRANT TRAINS

There are other ways in which the immigrant's journey needs safeguarding. Regular, or at least occasional, trips on immigrant trains by inspectors are now generally recognized as the only way of preventing the kind of exploitation from which, it has been discovered, the immigrant often suffers during the railroad journey to some interior point.

Congress has passed a law designed to protect the immigrant on his journey from the port to the interior, but unfortunately, the necessary appropriation for carrying it into effect has not been made.

THE IMMIGRANT HEAD TAX SUFFICIENT TO PAY FOR ADEQUATE PROTECTION AND SUPERVISION

Because of the interstate character of the work, and the fact that the control of the admission of the immigrant is a federal matter, all the increased supervision at the docks, on the boats, at the railroad stations, and on the trains, can, it is believed, best be given by the United States Bureau of Immigration.

It is only fair that it should do so, for the United States collects a head· tax of $4 from every immigrant who comes. In the year ending June 30, 1913, this head tax, for the port of Boston alone, amounted to $254,872. The expenses of the immigration service in Boston amounted to only 5102,618.70.

It is surely not the intention of the federal government to levy upon the immigrant a tax for general purposes at the time of his admission, when his little capital is so much needed; therefore, the money collected in this way should be regarded as a trust fund to be devoted entirely to improving and extending the United States immigration service.

The use of a tiny part of the $152,253, the difference between the amount collected and that spent in Boston, would enormously improve conditions in Massachusetts.

But the Commonwealth cannot give up all sense of responsibility. The standard of protection at the port of Boston should, because there are fewer arrivals, be higher than that on Ellis Island. The reverse has been true in the past, but neither the Commonwealth nor the city of Boston has realized this fact.

No test has yet been made of what might be accomplished by a display of interest on the part of the local government. During the very short life of this commission, important improvements have been secured by merely calling attention to conditions which its investigations revealed. A permanent Board of Immigration could do much more.

“Section 1: Arrival and Transit.” In The Problem of Immigration in Massachusetts, Report of the Commission on Immigration, Chapter VIII: Protection against Abuses and Frauds to Which the Immigrant Is Particularly Liable, 1914, Pages 162-175.