Roasting - Vintage Cooking Process

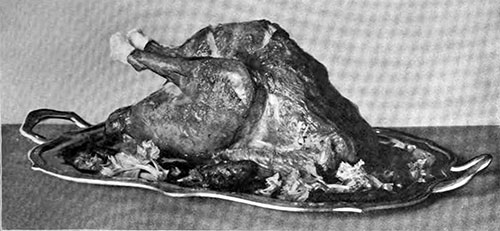

Roast Turkey with Garnish © 1912 American Cookery

Roasting is really cooking before a clear fire, but the modern oven ventilated and heated by radiation provides a good substitute for the ancient revolving spit.

Roasting is one of the oldest methods of cooking on record, and still remains the favorite form of cooking joints of meat or birds. Roasting proper is a culinary operation by which a joint of meat, a small whole carcass, or a bird is exposed to an open clear fire, so that it may become first browned over its surface and ultimately cooked tender.

The intense heat, combined with the free action of the hot air, produces and imparts that savory taste and fine flavor which is quite unlike that obtained in any other way. Some hold that this process of cooking excels all other forms.

Rule for Success

The success of every method of cooking depends largely upon the correct management of the fire. In roasting, this is particularly the case, as for roasting a clear, brisk and yet steady fire is needed.

Although roasting implies the application of an intense degree of heat, expecting for a brief period, during which the surface of a joint is browned, roasting before a fire is cooking by radiated heat, namely the heat rays coming from the fire are caught by the joint hanging before it.

This can be effected by either a closed or open range.

To roast a joint, it should be placed before great heat for the first ten minutes and then be allowed to cook more slowly.

The great heat hardens the outside of the meat and keeps in the juices. If allowed to cook quickly all the time, the meat is likely to be tough. The fire should be bright and clear.

The joint should be basted about every ten minutes, as this helps to cook it, keep it juicy and improves the flavor.

The time allowed is fifteen minutes for every pound, twenty minutes over for beef and mutton; for veal and pork twenty minutes for every pound and thirty minutes over. [1]

Roasting is cooking before a clear fire, with a reflector to concentrate the heat. Heat is applied in the same way as for broiling, the difference being that the meat for roasting is placed on a spit and allowed to revolve, thicker pieces alway being employed.

Tiu-kitchens are now but seldom used. Meats cooked in a range oven, though really baked, are said to be roasted. Meats so cooked are pleasing to the sight and agreeable to the palate, although, according to Edwart! Atkinson, not so easily digested as when cooked at a lower temperature in the Aladdin oven. [2]

The chief point to remember in roasting is that the meat should be quickly browned in order that the crust thus formed may retain the juices. The oven should therefore be hot when the meat is put in and the heat, if possible, gradually reduced.

Wipe the meat with a damp cloth, but do not wash it. Sprinkle with pepper and salt and just a. little flour, and put in a pan with a small piece of fat or drippings. When the meat is scared, add a little water and baste every ten minutes.

When one side is thoroughly browned, turn over and brown the other side. When done, remove the roast; pour off almost all of the fat and make a brown sauce according to the directions in the' chapter on “Sauces.”

If the meat is very lean it is a good plan to lay thin slices of fat meat, bacon or pork over the top.

Roasting Method of Cooking

Roasting is a truly English method of cooking, roast beef being one of our national dishes. It is a great pity that, in consequence of the construction of many modern kitchen ranges, roasting, properly speaking, has to a great extent become a thing of the past, because the flavor of baked meat is never so fine as that which is cooked by the direct action of an open fire.

“In one sense of the term,” says the author of Kettner’s ‘Book of the Table,’“ roasting is something distinct from baking, broiling, and frying; according to another, it includes baking, broiling and frying. In the widest sense, to roast is to cook food by the application to it of a roasting heat, and a roasting heat may be described as the highest degree of heat which will cook food without burning it up and destroying it.”

Rules for Roasting

To roast successfully, a clear fire is essential. The fire should be made up, and if necessary to replenish it while the meat is cooking, coals should be put on at the back and the live embers drawn to the front to avoid any smoke.

In case it is sometimes possible to have it, it is well to know that a wood fire is far preferable to a coal fire, both for roasting and broiling. When a roaster is used, it should be placed in front of the lire to get hot before the meat is hung in it.

The thickest part of the meat should be downwards, because the heat is greater from the lower part of the fire. If the joint is not fat, some dripping should be placed in the pan ready for basting.

Having fastened the meat to the jack, or worsted, place the roaster close to the fire for the first fifteen minutes, that the extreme heat may at once seal up the outside by hardening the albumen in the surface of the joint; afterwards draw the roaster further from the fire and cook gradually, basting every fifteen minutes.

To baste is to pour fat two or three times over the joint. Doing this prevents the meat drying up, and gives it a better flavor. Mr. Buckmaster says that the essential condition of good roasting is constant basting.

The general rule as regards length of time allowed for Toasting is a quarter of an hour to each pound, but that must only be taken as a guide, not as an absolute rule.

The size and shape of the joint must be considered, as well as its weight. If the rule were strictly adhered to, some joints with a great deal of bone would get dried up while others would not be cooked through.

Well-hung meat will cook in a shorter time than that freshly killed. Meat will cook in a shorter time in summer than in winter. Frozen meat will take longer to cook than fresh, and should always be allowed quite two hours to thaw, and much longer,

if possible, before it is put to the fire. Thick joints of veal and pork generally take twenty minutes to the pound. When the steam from the meat draws to the fire it is generally done enough for most people’s tastes.

To roast well requires the experience gained from practice and observation.

The gravy for a joint may be made in two ways; this is one—Take the dripping-pan away half an hour before the joint is cooked, and put a dish in its place.

Pour the whole contents of the dripping-pan into a baking-tin or shallow pan and put it in a very cold place, so that the fat will quickly cake on the top of the gravy; it must then be removed and the gravy made hot; a little salt should be added to it.

Pour the gravy round the joint, not over it—as doing so destroys the crisp surface of the meat. It ought to be scarcely necessary to add that roasted meat should be served on a thoroughly heated dish, and, to be in perfection, should be sent to table directly it comes from the fire.

This is the more ordinary method of making gravy: just before taking up the joint take away the dripping- pan, put a dish in its place, tilt it and let all the fat run into a basin, then pour into the pan a small quantity of boiling water, and scrape up all the brown glaze which adheres to the bottom of the pan; add a little salt, and, if necessary, color carefully with a little burnt sugar; too much of this will spoil the flavor of the gravy.

With regard to flouring the joint there are great differences of opinion, some people like it, and others do not. When it is preferred, flour the joint half an hour before taking it up and put it a little nearer to the fire to get brown and cook the flour, but do not let it burn. In all roasting when the joint is nearly cooked put it nearer to the tire again to get a nice crisp surface.

When a roasting-jack is not available, use a strong rope of worsted in the place of it.

The Dutch oven is most convenient for small roasts.

[1] Table Talk: The American Authority upon Culinary Topics and Fashions of the Table, Vol. XXVII, 1912, A Series of Articles Published Throughout the Year. Published Monthly by The Arthur H. Crist Co., Cooperstown, NY. A Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Interests of American Housewives, Having special reference to the Improvement of the Table. Marion Harris Neil, Editor.

[2] Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-school Cook Book, Revised Edition, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company (1912), p. 20