Baking - Vintage Cooking Process

In baking and pastry, the most significant tool for a pastry chef is the oven. The attention and maintenance of this central apparatus in the kitchen are the fundamentals of baking.

This is the most convenient form of cooking. Baking is cooking in hot air and hot air plays a very important part in cooking. Although baking in a closed oven is not done by radiant heat, there is a great amount of heat radiated from the sides of the oven and from the top and bottom.

The hot air in an oven is likely to become tainted with the fumes of burnt grease and smoke, which too often communicates disagreeable flavors to things baked more especially to meats.

This can be avoided to a large extent if the oven is kept scrupulously clean and well ventilated. For braising, roasting and baking bread, cakes, pastry, puddings, custards and many savory meats, vegetable and farinaceous dishes, the oven will always remain in favor.

Difference Between Baking and Boiling

The difference between baking and boiling is that by the former method, the food is cooked by dry heat, whilst by the latter is cooked by liquid heat. Baking, as compared with other cooking processes such as broiling and roasting, differs in this.

Broiling and roasting the food is cooked by full exposure to the hot air, baking is performed in ovens, more or less closed structures whereby the action of dry heat is modified by the presence of the steam that comes from the food which is being baked.

THE OVEN AND BAKING IN THE 1900s

Nothing to this day has been invented to supersede the old-fashioned brick and stone oven heated with wood.

Cast iron and sheet iron ovens, owing to the ease with which they can be moved, are no doubt valuable for an army and all other migratory purposes, but that is their only advantage.

It is next to impossible to turn out of one of them successfully any of the larger pieces of pastry, such as large sponge cakes, babas, etc.

These, when baked in a brick oven, attain their proper degree of cooking gently, the heat of the oven decreasing as the baking progresses, and the steam escaping easily through the open door of the oven.

Whereas in a closed iron oven it is otherwise - the heat not being retained by the material has to be maintained during the whole time of baking at very nearly one uniform temperature, the steam is consequently more abundant, and, as it cannot escape through the closed door, sodden whatever may be baking; hence the superiority of the brick oven, and the cause of the greater facility it affords for all kinds of baking.

Before attending to anything else, the first care must be to see to the heating of the oven (none but dry wood should be used), the pieces should be built up around the sides of the oven, and lighted with brushwood or shavings, care being taken that the wood burns freely, because, should it turn black in places, and burn unevenly, the oven would be unequally heated.

When all the wood is burnt, spread the live ashes evenly over the hearth of the oven with the rake and add a few more logs of wood; continue this until the whole interior of the oven is quite white, then rake up the ashes to the mouth of the oven, put two or three logs of wood on them.

When this last wood is consumed, close the oven for a quarter of an hour, after which rake out all the ashes, clean the oven thoroughly with a wet swab, and shut it.

An oven which has not been in use for a month or more should be heated on two consecutive days before anything is put to bake in it. If this is impossible, and it is required for use the same day, light the oven with wood and brushwood as above.

After two hours smooth the ashes over the hearth and shut the oven for two hours, then light wood in it again, and keep it burning for another two hours; when all the wood is burnt, draw the ashes to the front, close the oven for twenty minutes, then clean it and close it till wanted for use.

To ascertain the temperature of the oven, put half a sheet of white kitchen paper on the hearth, and shut the oven door; if the paper immediately catches fire, the oven is too hot.

Close the oven again, and ten minutes later put in another piece of paper; should it char without lighting the oven will still be too hot. Ten minutes later introduce a third piece of paper, and, should it be scorched to a dark brown color, without igniting, the oven will be of the proper temperature for baking all small pastry which requires glazing by the oven; for future reference, I shall describe this degree of heat in the text as dark brown paper heat.

The temperature a few degrees below this, tested by a piece of paper, in the same way, referred to as light brown paper heat, suitable for baking vol-au-vents, hot pie crusts, timbale crusts, etc.

Dark yellow paper heat will refer to the temperature suitable for baking the larger pieces of pastry.

Finally, light yellow paper heat will designate the temperature proper for baking manqué, genoises, meringues, and generally all small pastry which does not require glazing.

It is always advisable to time the introduction into the oven of the larger pieces of pastry as a check upon their apparent perfect baking.

Many signs upon the cakes or pies themselves will reveal to the watchful and practiced eye of the cook whether their baking is completed; for instance, a brioche will be quite cooked when the cracks of the top crust are of a pale-yellow color.

A large sponge cake will be adequately baked if on trying it with the finger it is found spongy and elastic.

It can also be tried by inserting the blade of a knife into it; if the blade is withdrawn clean and free from dampness, the sponge cake may be turned out of the mold.

As a rule, baking in a slack oven must be avoided; the other extreme is preferable, and it is better to have to scrape off a little of the burnt bottom paste than to have pastry lingering too long in the oven—a process which will never produce a good or wholesome article of food.

If the pressure of time compels putting pastry to bake in too hot an oven, it is expedient to put a second baking sheet under the first, to cover the top of the cake with paper, and to leave the oven open or only partially closed.

In fact, an oven should never be entirely closed during the baking process; to close it prevents the escape of the steam and interferes with the baking.

For larger pastry, an oven must be very equally heated and allowed to cool partially to the exact temperature required.

PORTABLE OVEN

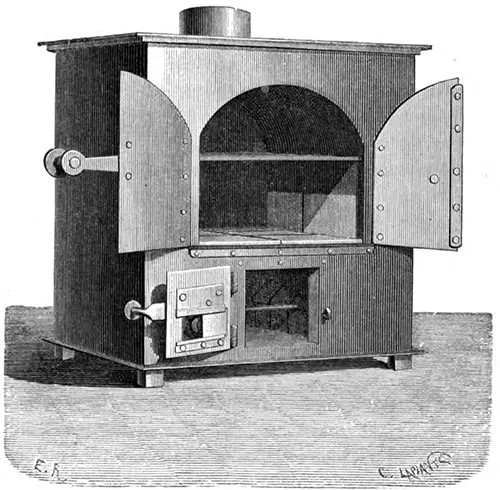

Below is a sketch of a portable sheet iron oven well adapted for general use in small households, far superior to the ordinary cast iron oven of a stove or kitchener; it will bake in a very credible way all small pastry, petits-fours, souffles, gratins, etc., and it will also bake meat (a very efficient substitute for roasting it).

Portable Oven

It is inexpensive, a small consumer of fuel, and not liable to get out of order. It can be placed anywhere and is considered a very successful invention.

When wanted for use, the fire is lighted and kept burning for half an hour, after which more or less fire is kept up according to the dishes to be cooked.

When fixed in a fire-place, a sheet iron pipe about four feet long must be adapted to the flue at the top of the oven to carry the smoke up the chimney; if there is no fireplace in the room a longer length of pipe will be required with an outlet through the wall for the smoke to escape.

TERMS USED IN PASTRY RECIPES

Boiling of Sugar

Break up some good loaf sugar into pieces with a chopper (the top of the loaf is the best), put it into a perfectly clean copper sugar-boiler, pour in sufficient filtered water to barely cover the sugar, and add a good pinch of Cream of Tartar. When the sugar is thoroughly melted, put it over a brisk fire.

When the syrup registers 40° C. on the saccharometer, dip a copper skimmer into it, blow through the holes of the skimmer, and if the syrup produces small air bubbles, it has attained the degree of boiling known as to the blow.

Boil the syrup again, and try it by skimming off, with the tip of your finger, a particle of the syrup, and transferring the finger rapidly into a basin of cold water. If the sugar can be rolled up into a ball, it has attained the degree known as the softball.

After a little more boiling, the syrup will have acquired more consistency, and, when tried in the same way, will roll up to a harder ball, and this we will call to the ball.

After still more boiling, when the finger is first dipped into the syrup and then into the water, and the sugar comes off in a brittle piece, which will break with a slight snap, the degree known as to the crack is attained. A little more boiling will bring it to the hard crack, in which state it is used for caramel glazing and for spun sugar.

Considerable attention is required at this stage to take the syrup off the fire at the right point of boiling, as a few seconds beyond it would give it a yellow tinge and make it useless for most purposes.

Icing

A mixture of pounded sugar, sifted through a silk sieve, and of the white of an egg.

Sugared Almonds

Almonds blanched and chopped, mixed in fine sugar and white of egg, ready to spread on small cakes, biscuits, etc.

To blanch

To scald almonds, pistachios, etc., so as to remove the skins.

To flute

To cut paste with a fluted cutter or with a small knife; vol-au-vent crusts, puff paste cakes, etc., are cut in this way.

To line

To place paste at the bottom and round a mold; a mold is lined thinly or thickly, as required, and as will be indicated in each recipe.

To score

To make incisions forming a pattern on the top of paste cakes.

To shrink

Paste should be rolled out and allowed to rest before it is cut to shape; this will prevent its shrinking afterward.

To give a turn

When puff paste is mixed, roll it out to a length of about three feet, then fold over one-third of the length and fold the other third over this; this operation is called giving: one turn.

To whip

To beat eggs or cream with a whisk; thin paste is also whipped with the hand.

To work

To beat up mixtures of egg, cream, butter, flour, water, etc., with a wooden spoon or spatula; paste is also worked on the board with the hands, to mix it thoroughly.

Rules for Baking Meat

In baking meat there are two or three points which should bo most carefully attended to. The oven should be well ventilated and kept perfectly clean. The baking-tin must also be scrupulously clean; any juice from fruit or meat gravy which has been spilt in the oven, or on the baking-tin, and not removed, will burn and give an unpleasant taste to the meat.

The baking-tin, if possible should bo a double one. For the first half-hour the oven should be hot, afterwards it must be kept at a moderate heat. If this is not done, the outside of the meat will scorch and dry up before the inside is cooked.

The basting should be as constant as when the meat is roasted. The oven should be made hot again at the finish to ensure the surface being nice and crisp.

The common fault in baking is to have the oven too hot, and then the meat gets dried up and wasted. As a general rule twenty minutes to the pound will not be too long if the oven is at the right temperature, but all the conditions mentioned in the rules for roasting must be taken into consideration.

Always put the meat on a trivet; do not let it soak in its own fat.

Gravy is made as for roasted meat.