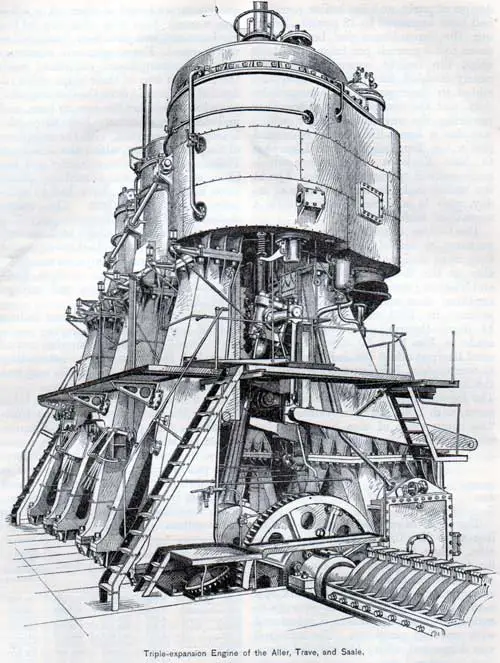

The Triple Expansion Engine - 1887

The establishment of the Collins line was one of the great events of steamship history. We had been so successful upon our coasts, rivers, and lakes, that it was but natural we should make some effort to do our part with steam upon the greater field of international trade.

Triple-expansion Engine of the Aller, Trave, and Saale.

It was impossible that the monopoly which had existed for ten years in the hands of the Cunard company should not be combated by someone, and with the advent of the Collins line came a strife for supremacy, the memories of which are still vivid in the minds of thousands on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Cunard company at this time had increased their fleet by the addition of the America, Niagara, Europa, and Columbia, all built in 1848. Their machinety did not differ materially from that of the preceding ships, in general design, but there had, in the course of practice, come better workmanship and design of parts, and the boiler pressure had been increased to 13 pounds, bringing the expenditure per horse-power down to 3.8 pounds per hour.

In these ships the freight capacity had been nearly doubled, fifty per cent. had been added to their passenger accommodation, and the company was altogether pursuing the successful career which was due a line which could command $35 a ton for freight from Liverpool to New York-a reminiscence which must make it appear the Golden Age to the unfortunate steamship-owner of today, who is now most happy with a seventh of such earnings.

The Collins steamers were a new departure in model and arrangement; they were designed by Steers, famous also as the designer of the America and Niagara; exceeded in size and speed anything then afloat, and reduced the journey in 1851 and 1852 to about 11 days-though some voyages were made in less than 10 days.

The Cunard line put afloat the Asia and Africa, as competitors, but they neither equalled the American steamers in size nor speed. The former were of 3,620 tons displacement, with 1,000 indicated horse-power. The comparison of size between them and the Collins steamers is as follows :

| Length | Depth | Beam | Draught | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ft. | ft. | in. | ft. | ft. | in. | |

| Arctic | 282 | 32 | 45 | 20 | ||

| Asia | 266 | 27 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 9 |

The three other vessels of the Collins line were the Baltic, Atlantic, and Pa cific. They formed a notable fleet, and fixed for many years to come the type of the American steamship in model and arrangement.

They were the work of a man of genius who had the courage to cast aside tradition where it interfered with practical purposes. The bowsprit was dispensed with; the vertical stem, now so general, was adopted, and everything subordinated to the use of the ships as steamers.

But great disaster was in store for these fine ships. The Arctic, on September 21, 1854, while on her voyage out, was struck by the French steamer Vesta, in a fog off Cape Race, and but 46 out of the 268 persons on board were saved.

The Pacific left Liverpool on June 23, 1856, and was never heard of after. The Adriatic, a much finer ship than any of her predecessors, was put afloat; but the line was doomed.

Extravagance in construction and management, combined with the losses of two of their ships and a refusal of further aid from the Government, were too much for the line to bear, and in 1858 the end came.

Ever since, the European companies, with the exception of the time during which the line from Philadelphia has been running and the time during which some desultory efforts have been put forth, have had to compete among themselves.

The sworn statement of the Collins company had shown the first four ships to have cost $2,944,142.71. The actual average cost of each of the first 28 voyages was $65,215.64; and the average receipts, $48,286.85-showing a loss on each voyage of $16,928.79.

To discuss the causes of our failure to hold our own in the carrying trade of the world may seem somewhat out of place, but the subject is so interesting in many ways that a few words may not be amiss.

The following is a comparative table showing the steam tonnage of the United States and of the British Empire, beginning with the year in which ocean steam navigation may be said to have been put fairly on its feet.

Our own is divided into " oversew," or that which can trade beyond United States waters, and " enrolled," which includes all in home waters :

| United States | Total | British Empire (including colonies) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oversea | Enrolled | |||

| 1838 | 2,791 | 190,632 | 193,423 | 82.716 |

| 1840 | 4.155 | 198,184 | 202,339 | 95.807 |

| 1842 | 4,701 | 224,960 | 229.681 | 118,930 |

| 1844 | 6,909 | 265,270 | 272.179 | 125,675 |

| 1846 | 6,287 | 341,606 | 347,893 | 144,784 |

| 1848 | 16,068 | 411,823 | 427,891 | 168,078 |

| 1850 | 44,942 | 481.005 | 525,947 | 187,631 |

| 1852 | 79,704 | 563,536 | 643,240 | 227,106 |

| 1854 | 95,036 | 581,571 | 676,607 | 326,484 |

| 1855 | 115,045 | |||

| 1856 | 89,715 | 583,362 | 673,077 | 417,717 |

| 1858 | 78,027 | 651,363 | 729,390 | 488.415 |

| 1860 | 97,296 | 770,641 | 867.937 | 500,144 |

It will be seen from this table how great the extension of the use of the steamboat had been in the United States in these earlier years, as compared with that elsewhere.

In 1852 our enrolled tonnage had grown to more than half a million tons, or well on to three times the whole of that of the British Empire, and our oversea tonnage was about one-third of that of Great Britain and her dependencies.