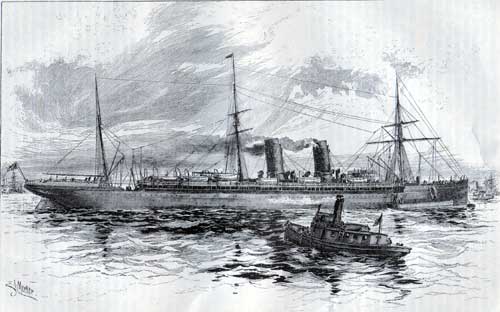

Great Eastern, Britannic, Etruria, Champagne - 1887

Joseph Bramah, in 1785, took out a patent for propelling vessels by steam, wherein, after describing the method figured in his specification of using a wheel at the stern of a vessel, in which he places the rudder at the bow, he proceeds as follows :

"Instead of this wheel A may be introduced a wheel with inclined fans, or wings, similar to the fly of a smoke-jack, or the vertical sails of a wind-mill. This wheel, or fly, may be fixed on the spindle C alone, and may be wholly under water, when it would, by being turned round either way, cause the ship to be forced backward or forward, as the inclination of the fans, or wings, will act as oars with equal force both ways; and their power will be in proportion to the size and velocity of the wheel, allowing the fans to have a proper inclination. The steam-engine will also serve to clear the ship of water with singular expedition, which is a circumstance of much consequence."

Bramah thus very clearly describes the screw, and in so doing must unquestionably be numbered as one of the many fathers of this system of propulsion. Fitch, as before stated, is recorded, on most trustworthy evidence, to have been another; and Mr. Stevens, of Hoboken. not only carried out successful experiments with the screw in 1804, at New York, but even experimented with twin screws. Charles Cummerow, " in the City of London, merchant," patented, in 1828, " certain improvements in propelling vessels, communicated to me by a certain foreigner residing abroad," in which the screw is set forth in a manner not to be questioned. Who the " certain foreigner " was, who communicated the invention to Mr. Cummerow, has not come down to us.

It had, however, like the steamboat as a whole, to wait for a certain preparedness in the human intellect. Invention knocked hard, and sometimes often, in the early years of the century, before the doors of the mind were opened to receive it; and too frequently then the reception was but a surly one, and attention deferred from visitor to visitor until one came, as did Fulton, or Ericsson, who would not be denied.

The transfer of Ericsson to America left an open field for Mr. Pettit Smith, and the experiments carried out by the Screw Propeller Company had the effect of permanently directing the attention in Great Britain of those interested in such subjects. The screw used in the Archimedes " consisted of two half-threads, of an 8 feet pitch, 5 feet 9 inches in diameter.

Each was 4 feet in length, and they were placed diametrically opposite each other at an angle of about 45 degrees on the propeller-shaft " (Lindsay). She was tried in 1839, and in 1840 Mr. Brunel spent some time in investigating her performance.

His mind, bold and original in all its own conceptions, was quick to appreciate the new method; and, although the engines of the Great Britain were already begun, designed for paddlewheels, he brought the directors of the company, who had undertaken the building of their own machinery, to consent to a change.

The following details of the ship are taken from the "Life of Brunel : " Total length, 322 ft.; length of keel, 289 ft.; beam, 51 ft.; depth, 32 ft. 6 in.; draught of water, 16 ft.; tonnage measurement, 3,443 tons; displacement, 2,984 tons; number of cylinders, 4; diameter of cylinder, 88 in.; length of stroke, 6 ft.; weight of engines, 340 tons; weight of boilers, 200 tons; weight of water in boilers, 200 tons; weight of screw-shaft, 38 tons; diameter of screw, 15 ft. 6 in.; pitch of screw, 25 ft.; weight of screw, 4 tons; diameter of main drum, 18 ft.; diameter of screw-shaft drum, 6 ft.; weight of coal, 1,200 tons.

"In the construction of the Great Britain, the same care which had been spent in securing longitudinal strength in the wooden hull of the Great Western was now given to the suitable distribution of the metal."

A balanced rudder was a part of her original construction, and the unusual method of lapping the plates will be noticed. " Apart from their size, the design of the engines of the Great Britain necessarily presented many peculiarities.

The boilers, which were 6 in number, were placed touching each other, so as to form one large boiler about 33 feet square, divided by one transverse and two longitudinal partitions.

"It would seem that the boiler was worked with a pressure of about 8 pounds on the square inch."

" The main shaft of the engine had a crank at either end of it, and was made hollow; a stream of water being kept running through it, so as to prevent heating in the bearings. An important part in the design was the method by which motion was transmitted from the engine-shaft to the screw-shaft, for the screw was arranged to go three revolutions to each revolution of the engines. Where the engines do not drive the screw directly, this is now universally effected by means of toothed gearing; but when the engines of the Great Britain were made, it was thought that this arrangement would be too jarring and noisy. After much consideration, chains were used, working round different-sized drums, with notches in them into which fitted projections on the chains."

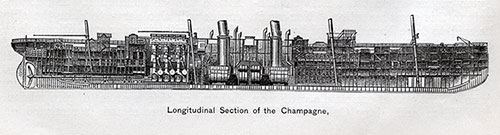

Longitudinal Section of the Champagne.

On July 19, 1843, this (for the time) great ship was floated out of dock; but it was not until January 23, 1845, that she left Bristol for London, making on her voyage an average of 12 1/3 knots an hour. She left Liverpool for New York on August 26th, and arrived on September 10th, having made the passage out in 14 days and 21 hours; she returned in 15i days.

During the next winter, after one more voyage to New York, alterations were made, to give a better supply of steam, and a new screw was fitted. She made two voyages to New York in 1846; and on September 22d she left Liverpool on a third, but overran her reckoning and stranded in Dundrum Bay, on the northeast coast of Ireland, when it was supposed she was only rounding the Isle of Man.

This unfortunate event completed the ruin of the company, already in financial straits through the competition of the Cunard line; and the ship, after her rescue, effected August 27, 1847, almost a year after grounding, was " sold to Messrs. Gibbs, Bright & Co., of Liverpool, by whom she was repaired and fitted with auxiliary enines of 500 nominal horse-power.

On a general survey being made it was found that she had not suffered any alteration of form, nor was she at all strained. She was taken out of dock in October, 1851, and since that time she has made regular voyages between Liverpool and Australia."

These last few lines appear in the "Life of Brunel," published in 1870. But she was later changed into a sailing-ship, and only last year (1886) stranded again at the Falkland Islands.

She has been floated; but being badly injured, was sold to serve as a hulk, and there no doubt will be passed the last days of what may be regarded one of the famous ships of the world. She was, for the time, as bold a conception as was her great designer's later venture, the Great Eastern.

The Chilian Cruiser Esmeralda.

The acceptance by the English Government of the Cunard company's bid for the contract for carrying the mails to America resulted in putting afloat, in 1840, the Acadia, Britannia, Columbia, and Caledonia.

The first vessels of the Cunard line were all wooden paddlewheel steamers, with engines by Napier, of Glasgow, of the usual side-lever class; the return-flue boilers and jet-condensers were used, the latter holding their place for many years to come, though surface condensation had already appeared as an experiment.

The company was to carry the mails fortnightly between Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston, regular sailings to be adhered to, and four vessels to be employed, for the sum of £81,000 ($400,000) per annum.

The contract was made for seven years, but was continued from time to time for forty-six—no break occurring in this nearly half-century's service until within a short time of the present writing, when the Umbria—November 4, 1886—was the first ship in the history of the company to leave Liverpool on the regular day of sailing for America without mails.

The Britannia was the first of the fleet to sail; and, strange to say (from the usual seaman's point of view), Friday, July 4, 1840, was the day selected. She arrived at Boston in 14 days and 8 hours, a very successful passage for the time.

It must have required considerable moral courage in the projectors to inaugurate such an undertaking on a day of the week which has been so long on the black-list of sailor superstition, notwithstanding it had the advantage of being the anniversary of the Declaration of American Independence.

The success of this line ought certainly to rehabilitate Friday to a position of equality among the more fortunate days, though it will be observed that none of the transatlantic lines have yet selected it as a day of sailing.

The Britannia, which was representative of the quartette, was of the following dimensions : Length of keel and fore rake, 207 ft.; breadth of beam, 34 ft. 2 in.; depth of hold, 22 ft. 4 in.; mean draught, 16 ft. 10 in.; displacement, 2,050 tons; diameter of cylinder, 72 1/2 in.; length of stroke, 82 in.; number of boilers, 4; pressure carried, 9 lbs. per sq. in.; number of furnaces, 12; fire-grate area, 222 ft.; indicated horse-power, 740; coal consumption per indicated horse-power per hour, 5.1 lbs.; coal consumption per day, 38 tons; bunker capacity, 640 tons; cargo capacity, 225 tons; cabin passengers carried, 90; average speed, 8.5 knots.

The Cunard Steam Ship Company Steamer Etruria

It will thus be seen that these ships were not an advance upon the Great Western, but were even slightly smaller, with about the same coal consumption and with rather less speed.

The Hibernia and Cambria followed in 1843 and 1845, 530 tons larger in displacement, with 1,040 indicated horsepower, and steaming about 9 1/2 knots per hour.

The plan (shown on page 521) gives an idea of these vessels which is far from fulfilling the ideas of the present Atlantic traveller, who considers himself a much-injured person if he has not electric lights and bells, baths ad libitum, and a reasonable amount of cubic space in which to bestow himself.

None of the least of these existed in the earlier passenger ships; a narrow berth to sleep in and a plentiful supply of food were afforded, but beyond these there was little—notwithstanding the whole of the ship was given up to first-cabin passengers, emigrants not being carried in steamers until 1850, and it was not until 1853 that any steamer of the Cunard line was fitted for their accommodation.

How little it was possible to do for the wanderer to Europe in those days may be seen when comparison shows the Britannia to have been but half the length of the Umbria, but two-thirds her breadth, but six-tenths her depth, with much less than half her speed, and less than one-twentieth her power.

The establishment of the Cunard line marked the setting of ocean steam traffic firmly on its feet. What in 1835 had been stated by one of the most trusted scientific men of that time as an impossibility, and even in 1838 was in doubt, had become an accomplished fact; and while the proof of the practicability of the American route was making, preparations were in progress for the extension of steam lines which were soon to reach the ends of the world.

A detailed statement of historic events is, of course, here out of place, but a mere mention of other prominent landmarks in steam navigation is almost a necessity.

The founding of the Peninsular Company, in 1837, soon to extend its operations, under the name of the Peninsular and Oriental, to India, and the establishment, in 1840, of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, are dates not to be passed by.

The establishment of the latter line was due to one of our own countrymen—William Wheelright, of Newburyport, who, when consul at Guayaquil, grasped the conditions of the coast, and through his foresight became one of its greatest benefactors, and at the same time one of its most successful men. He failed in interesting our own people in the venture, and turned to London, where his success was greater.

The Chili and Peru, the first vessels of this now great fleet, despatched in 1840, were but 198 feet long and of 700 tons. It was not until 1868 that the line was brought into direct communication with England by the establishment of monthly steamers from Liverpool to Valparaiso, via the Straits of Magellan.

They had to await the diminished fuel consumption, which the company itself did so much to bring about through compound engines and surface condensation.

In the following years we ourselves were not idle. In 1843 the celebrated screw steamer Princeton—whose name is connected in so melancholy a manner with the bursting of the "Peacemaker" and the death of the then Secretary of the Navy, when he and a number of other high officials were visiting the ship—was built for the navy after Ericsson's designs, and fitted with one of his propellers.

She was 164 feet long, with 30 feet 6 inches beam, and a displacement, at 18 feet draught, of 1,046 tons. She had a very flat floor, with great sharpness forward and excessive leanness aft. She may almost be taken as representative of the later type in model. She had three boilers, each 26 feet long, 9 feet 4 inches high, and 7 feet wide, with a grate-surface of 134 square feet.

In 1845, Mr. R. B. Forbes, of Boston, so long known for his intimate and successful connection with shipping interests, built the auxiliary screw steamers Massachusetts and Edith, for transatlantic trade.

The former was somewhat the larger, and was 178 feet long and 32 broad. Her machinery was designed by Ericsson, and had two cylinders, 25 inches diameter, working nearly at right angles to each other.

The machinery was built by Hogg & Delamater, of New York, and had the peculiarity of having the shaft pass through the stern at the side of the stern-post, under a patent of Ericsson's.

The propeller, on Ericsson's principle, was 9 feet diameter, and could be hoisted when the ship was under sail. She made but one voyage to Liverpool, and was then chartered by our Government to carry troops to Mexico, in 1846; but was later bought into the naval service, and known as the Farralones.

In June, 1847, the same year which witnessed the establishment of the Pacific Mail Company, the Washington, of 4,000 tons displacement, and of 2,000 indicated horse-power, was the pioneer of a line between New York and Bremen, touching at Southampton. The Hermann followed a little later, but was somewhat larger, the dimensions of the two ships being :

| Washington | Hermann | |

|---|---|---|

| Total length | 236 | 241 |

| Beam | 39 | 40 |

| Depth | 31 | 31 |

Their displacement was about 4,000 tons. The Franklin followed in 1848, and the Humboldt in 1850, both being a good deal larger than the two preceding The latter two were, however, employed only between New York and Havre.

In 1850 the Collins line was formed, with a large Government subsidy. In the same year the Inman line was established, with screw steamers built of iron—two differences from the prevailing construction, which were to bear so powerful an influence in a few years against the success of steamers of the type brought out by the Collins company.

In 1858 came the North German Lloyd, with the modest beginnings of its now great fleet, and in 1861 the French Corapagnie Transatlantique. In 1863 the National line was established; in 1866 the Williams & Guion (now the Guion), which had previously existed as a line of sailing-packets; and in 1870 the White Star.

These are those in which we are most interested, as they touch our shores; but in the interval other lines were directed to all parts of the world, few seaports remaining, of however little importance, or lying however far from civilization, that cannot now be reached by regular steam communication.

One reason for this very rapid increase in the enrolled tonnage was, of course, the fact that railroads had not yet begun to seam the West, as they were shortly to do; the steamboat was the great and absolutely necessary means of transport, and was to hold its prominence in this regard for some years yet to come.

When this change came, there came with it a change in circumstances which went far beyond all other causes in removing our shipping from the great place it had occupied in the first half of this century.

But great as was the effect worked by this change, there were certain minor causes which have to be taken into account. We had grown in maritime power through the events of the Napoleonic wars—which, though they worked ruin to many an unlucky owner, enriched many more—as we were for some years almost the only neutral bottoms afloat; we had rapidly increased this power during the succeeding forty years, during which time our ships were notably the finest models and the most ably commanded on the seas; the best blood of New England went into the service, and one has but to read the reports of the English parliamentary commissions upon the shipping subject to realize the proud position which our ships and, above all, our ships' captains held in the carrying trade.

We had entered the steam competition with an energy and ability that promised much, but we gave little or no heed to changes in construction until long after they had been accepted by the rest of the world; and it is to this conservatism, paradoxical as the expression may seem applied to our countrymen, that part of our misfortune was due.

The first of the changes we were so unwilling to accept was that from wood to iron; the other was that from paddle to screw. Even so late as the end of the decade 1860-70, while all the world else was building ships of iron, propelled by screws, some of which were driven by compound engines, our last remaining great company, the Pacific Mail, put afloat four magnificent failures (from the commercial point of view), differing scarcely in any point, except in size, from those of 1850-56.

They were of wood, and had the typically national overhead-beam engine. They were most comfortable and luxurious boats; but the sending them into the battle of commerce, at such a date, was like pitting the old wooden three-decker with her sixty-four pounders against the active steel cruiser of today and her modern guns.

Many of the iron screws built at the same time are still in active service; but the fine old China, America, Alaska, and Japan are long since gone, and with them much of the company's success and fortune.

Of course, one great reason for this non-acceptance was the fact that, with us, wood for ship-building was still plentiful, and that it was cheaper so to build than to build in iron, to which material English builders were driven by an exact reversal of these conditions; and the retention of the paddle over the screw was due in a certain degree to the more frequent necessity of repair of wooden screw ships, to which it is not possible to give the necessary structural strength at the stern to withstand successfully the jarring action of the screw at high speeds.

The part in advancing the British commercial fleet played by the abrogation of the navigation laws, in 1849, which had their birth in the time of Cromwell (and to which we have held with such tenacity, as ours were modelled upon theirs), need only be barely mentioned.

British ship-owners were in despair at the change, and many sold off their ship property to avoid what they expected to be the ruin of the shipping trade, but the change was only to remove the fetters which they had worn so long that they did not know them as such.

But the great and overwhelming cause, to which the effect of our navigation laws was even secondary, was the opening up of the vast region lying west of the earlier formed States; the building of our gigantic system of railways; the exploitation, in a word, of the great interior domain, of the possibilities of which, preceding 1850, we were only dimly conscious, and so much of which had only just been added by the results of the Mexican War.

It is so difficult, from the standpoint of this present year of 1887, to realize the mighty work which has been done on the American continent in this short space of thirty-seven years, that its true bearings on this subject are sometimes disregarded.

The fact that the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, at this date, was not running its trains beyond Cumberland, Md., will give an impression of the vastness of the work which was done later.

The period 1850-60 cannot be passed over without a mention of the Great Eastern, though she can hardly be said to have been in the line of practical development, which was not so much in enlargement of hull as in change in character of machinery.

Brunel's son, in his "Life " of his father, says : "It was no doubt his connection with the Australian Mail Company (1851-53) that led Mr. Brunel to work out into practical shape the idea of a great ship for the Indian or Australian service, which had long occupied his mind."

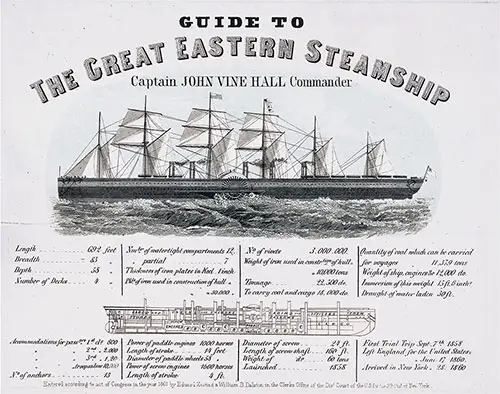

Great Eastern Steamship. (1860) Guide to the Great Eastern Steamship. Captain John Vine Hall commander. n. p. New York. GGA Image ID # 13ec897b4e

The Great Eastern was to attempt to solve by her bulk the problem which was later to be solved by high pressures and surface condensation. The ship finally determined on was 680 feet long, 83 feet broad, with a mean draught of 25 feet, with screw engines of 4,000 indicated horse-power and paddle engines of 2,600, to work with steam from 15 to 25 pounds pressure—thus curiously uniting in herself at this transition period the two rival systems of propulsion.

She was begun at Millwall, London, in the spring of 1854, and was finally launched, after many difficulties, on January 30, 1858. Her history is too well known to be dwelt upon here.

She has experienced many vicissitudes and misfortunes, and it is well that her great projector (who paid for her with his life, as he died the year after her launching) did not live to see her used as an exhibit, in 1886, in the River Mersey, her great sides serving to blazon the name and fame of a Liverpool clothing establishment.

Joseph Bramah, in 1785, took out a patent for propelling vessels by steam, wherein, after describing the method figured in his specification of using a wheel at the stern of a vessel, in which he places the rudder at the bow, he proceeds as follows :

"Instead of this wheel A may be introduced a wheel with inclined fans, or wings, similar to the fly of a smoke-jack, or the vertical sails of a wind-mill. This wheel, or fly, may be fixed on the spindle C alone, and may be wholly under water, when it would, by being turned round either way, cause the ship to be forced backward or forward, as the inclination of the fans, or wings, will act as oars with equal force both ways; and their power will be in proportion to the size and velocity of the wheel, allowing the fans to have a proper inclination. The steam-engine will also serve to clear the ship of water with singular expedition, which is a circumstance of much consequence."

Bramah thus very clearly describes the screw, and in so doing must unquestionably be numbered as one of the many fathers of this system of propulsion.

Fitch, as before stated, is recorded, on most trustworthy evidence, to have been another; and Mr. Stevens, of Hoboken. not only carried out successful experiments with the screw in 1804, at New York, but even experimented with twin screws. Charles Cummerow, " in the City of London, merchant," patented, in 1828, " certain improvements in propelling vessels, communicated to me by a certain foreigner residing abroad," in which the screw is set forth in a manner not to be questioned. Who the " certain foreigner " was, who communicated the invention to Mr. Cummerow, has not come down to us.

It had, however, like the steamboat as a whole, to wait for a certain preparedness in the human intellect. Invention knocked hard, and sometimes often, in the early years of the century, before the doors of the mind were opened to receive it; and too frequently then the reception was but a surly one, and attention deferred from visitor to visitor until one came, as did Fulton, or Ericsson, who would not be denied.

The transfer of Ericsson to America left an open field for Mr. Pettit Smith, and the experiments carried out by the Screw Propeller Company had the effect of permanently directing the attention in Great Britain of those interested in such subjects. The screw used in the Archimedes " consisted of two half-threads, of an 8 feet pitch, 5 feet 9 inches in diameter.

Each was 4 feet in length, and they were placed diametrically opposite each other at an angle of about 45 degrees on the propeller-shaft " (Lindsay). She was tried in 1839, and in 1840 Mr. Brunel spent some time in investigating her performance. His mind, bold and original in all its own conceptions, was quick to appreciate the new method; and, although the engines of the Great Britain were already begun, designed for paddlewheels, he brought the directors of the company, who had undertaken the building of their own machinery, to consent to a change.

The following details of the ship are taken from the "Life of Brunel : " Total length, 322 ft.; length of keel, 289 ft.; beam, 51 ft.; depth, 32 ft. 6 in.; draught of water, 16 ft.; tonnage measurement, 3,443 tons; displacement, 2,984 tons; number of cylinders, 4; diameter of cylinder, 88 in.; length of stroke, 6 ft.; weight of engines, 340 tons; weight of boilers, 200 tons; weight of water in boilers, 200 tons; weight of screw-shaft, 38 tons; diameter of screw, 15 ft. 6 in.; pitch of screw, 25 ft.; weight of screw, 4 tons; diameter of main drum, 18 ft.; diameter of screw-shaft drum, 6 ft.; weight of coal, 1,200 tons.

"In the construction of the Great Britain, the same care which had been spent in securing longitudinal strength in the wooden hull of the Great Western was now given to the suitable distribution of the metal."

A balanced rudder was a part of her original construction, and the unusual method of lapping the plates will be noticed. " Apart from their size, the design of the engines of the Great Britain necessarily presented many peculiarities. The boilers, which were 6 in number, were placed touching each other, so as to form one large boiler about 33 feet square, divided by one transverse and two longitudinal partitions.

"It would seem that the boiler was worked with a pressure of about 8 pounds on the square inch."

" The main shaft of the engine had a crank at either end of it, and was made hollow; a stream of water being kept running through it, so as to prevent heating in the bearings.

An important part in the design was the method by which motion was transmitted from the engine-shaft to the screw-shaft, for the screw was arranged to go three revolutions to each revolution of the engines.

Where the engines do not drive the screw directly, this is now universally effected by means of toothed gearing; but when the engines of the Great Britain were made, it was thought that this arrangement would be too jarring and noisy.

After much consideration, chains were used, working round different-sized drums, with notches in them into which fitted projections on the chains."

Longitudinal Section of the Champagne.

On July 19, 1843, this (for the time) great ship was floated out of dock; but it was not until January 23, 1845, that she left Bristol for London, making on her voyage an average of 12 1/3 knots an hour.

She left Liverpool for New York on August 26th, and arrived on September 10th, having made the passage out in 14 days and 21 hours; she returned in 15i days.

During the next winter, after one more voyage to New York, alterations were made, to give a better supply of steam, and a new screw was fitted. She made two voyages to New York in 1846; and on September 22d she left Liverpool on a third, but overran her reckoning and stranded in Dundrum Bay, on the northeast coast of Ireland, when it was supposed she was only rounding the Isle of Man.

This unfortunate event completed the ruin of the company, already in financial straits through the competition of the Cunard line; and the ship, after her rescue, effected August 27, 1847, almost a year after grounding, was " sold to Messrs. Gibbs, Bright & Co., of Liverpool, by whom she was repaired and fitted with auxiliary enines of 500 nominal horse-power.

On a general survey being made it was found that she had not suffered any alteration of form, nor was she at all strained. She was taken out of dock in October, 1851, and since that time she has made regular voyages between Liverpool and Australia."

These last few lines appear in the "Life of Brunel," published in 1870. But she was later changed into a sailing-ship, and only last year (1886) stranded again at the Falkland Islands.

She has been floated; but being badly injured, was sold to serve as a hulk, and there no doubt will be passed the last days of what may be regarded one of the famous ships of the world. She was, for the time, as bold a conception as was her great designer's later venture, the Great Eastern.

The Chilian Cruiser Esmeralda.

The acceptance by the English Government of the Cunard company's bid for the contract for carrying the mails to America resulted in putting afloat, in 1840, the Acadia, Britannia, Columbia, and Caledonia.

The first vessels of the Cunard line were all wooden paddlewheel steamers, with engines by Napier, of Glasgow, of the usual side-lever class; the return-flue boilers and jet-condensers were used, the latter holding their place for many years to come, though surface condensation had already appeared as an experiment.

The company was to carry the mails fortnightly between Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston, regular sailings to be adhered to, and four vessels to be employed, for the sum of £81,000 ($400,000) per annum.

The contract was made for seven years, but was continued from time to time for forty-six—no break occurring in this nearly half-century's service until within a short time of the present writing, when the Umbria—November 4, 1886—was the first ship in the history of the company to leave Liverpool on the regular day of sailing for America without mails.

The Britannia was the first of the fleet to sail; and, strange to say (from the usual seaman's point of view), Friday, July 4, 1840, was the day selected. She arrived at Boston in 14 days and 8 hours, a very successful passage for the time.

It must have required considerable moral courage in the projectors to inaugurate such an undertaking on a day of the week which has been so long on the black-list of sailor superstition, notwithstanding it had the advantage of being the anniversary of the Declaration of American Independence.

The success of this line ought certainly to rehabilitate Friday to a position of equality among the more fortunate days, though it will be observed that none of the transatlantic lines have yet selected it as a day of sailing.

The Britannia, which was representative of the quartette, was of the following dimensions : Length of keel and fore rake, 207 ft.; breadth of beam, 34 ft. 2 in.; depth of hold, 22 ft. 4 in.; mean draught, 16 ft. 10 in.; displacement, 2,050 tons; diameter of cylinder, 72 1/2 in.; length of stroke, 82 in.; number of boilers, 4; pressure carried, 9 lbs. per sq. in.; number of furnaces, 12; fire-grate area, 222 ft.; indicated horse-power, 740; coal consumption per indicated horse-power per hour, 5.1 lbs.; coal consumption per day, 38 tons; bunker capacity, 640 tons; cargo capacity, 225 tons; cabin passengers carried, 90; average speed, 8.5 knots.

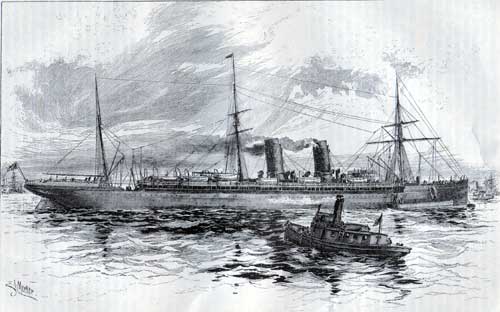

The Cunard Steam Ship Company Steamer Etruria

It will thus be seen that these ships were not an advance upon the Great Western, but were even slightly smaller, with about the same coal consumption and with rather less speed.

The Hibernia and Cambria followed in 1843 and 1845, 530 tons larger in displacement, with 1,040 indicated horsepower, and steaming about 9 1/2 knots per hour.

The plan (shown on page 521) gives an idea of these vessels which is far from fulfilling the ideas of the present Atlantic traveller, who considers himself a much-injured person if he has not electric lights and bells, baths ad libitum, and a reasonable amount of cubic space in which to bestow himself.

None of the least of these existed in the earlier passenger ships; a narrow berth to sleep in and a plentiful supply of food were afforded, but beyond these there was little—notwithstanding the whole of the ship was given up to first-cabin passengers, emigrants not being carried in steamers until 1850, and it was not until 1853 that any steamer of the Cunard line was fitted for their accommodation.

How little it was possible to do for the wanderer to Europe in those days may be seen when comparison shows the Britannia to have been but half the length of the Umbria, but two-thirds her breadth, but six-tenths her depth, with much less than half her speed, and less than one-twentieth her power.

The establishment of the Cunard line marked the setting of ocean steam traffic firmly on its feet. What in 1835 had been stated by one of the most trusted scientific men of that time as an impossibility, and even in 1838 was in doubt, had become an accomplished fact; and while the proof of the practicability of the American route was making, preparations were in progress for the extension of steam lines which were soon to reach the ends of the world.

A detailed statement of historic events is, of course, here out of place, but a mere mention of other prominent landmarks in steam navigation is almost a necessity.

The founding of the Peninsular Company, in 1837, soon to extend its operations, under the name of the Peninsular and Oriental, to India, and the establishment, in 1840, of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, are dates not to be passed by.

The establishment of the latter line was due to one of our own countrymen—William Wheelright, of Newburyport, who, when consul at Guayaquil, grasped the conditions of the coast, and through his foresight became one of its greatest benefactors, and at the same time one of its most successful men.

He failed in interesting our own people in the venture, and turned to London, where his success was greater. The Chili and Peru, the first vessels of this now great fleet, despatched in 1840, were but 198 feet long and of 700 tons.

It was not until 1868 that the line was brought into direct communication with England by the establishment of monthly steamers from Liverpool to Valparaiso, via the Straits of Magellan.

They had to await the diminished fuel consumption, which the company itself did so much to bring about through compound engines and surface condensation.

In the following years we ourselves were not idle. In 1843 the celebrated screw steamer Princeton—whose name is connected in so melancholy a manner with the bursting of the "Peacemaker" and the death of the then Secretary of the Navy, when he and a number of other high officials were visiting the ship—was built for the navy after Ericsson's designs, and fitted with one of his propellers. She was 164 feet long, with 30 feet 6 inches beam, and a displacement, at 18 feet draught, of 1,046 tons.

She had a very flat floor, with great sharpness forward and excessive leanness aft. She may almost be taken as representative of the later type in model. She had three boilers, each 26 feet long, 9 feet 4 inches high, and 7 feet wide, with a grate-surface of 134 square feet.

In 1845, Mr. R. B. Forbes, of Boston, so long known for his intimate and successful connection with shipping interests, built the auxiliary screw steamers Massachusetts and Edith, for transatlantic trade.

The former was somewhat the larger, and was 178 feet long and 32 broad. Her machinery was designed by Ericsson, and had two cylinders, 25 inches diameter, working nearly at right angles to each other.

The machinery was built by Hogg & Delamater, of New York, and had the peculiarity of having the shaft pass through the stern at the side of the stern-post, under a patent of Ericsson's.

The propeller, on Ericsson's principle, was 9 feet diameter, and could be hoisted when the ship was under sail. She made but one voyage to Liverpool, and was then chartered by our Government to carry troops to Mexico, in 1846; but was later bought into the naval service, and known as the Farralones.

In June, 1847, the same year which witnessed the establishment of the Pacific Mail Company, the Washington, of 4,000 tons displacement, and of 2,000 indicated horse-power, was the pioneer of a line between New York and Bremen, touching at Southampton. The Hermann followed a little later, but was somewhat larger, the dimensions of the two ships being :

| Washington | Hermann | |

|---|---|---|

| Total length | 236 | 241 |

| Beam | 39 | 40 |

| Depth | 31 | 31 |

Their displacement was about 4,000 tons. The Franklin followed in 1848, and the Humboldt in 1850, both being a good deal larger than the two preceding The latter two were, however, employed only between New York and Havre.

In 1850 the Collins line was formed, with a large Government subsidy. In the same year the Inman line was established, with screw steamers built of iron—two differences from the prevailing construction, which were to bear so powerful an influence in a few years against the success of steamers of the type brought out by the Collins company.

In 1858 came the North German Lloyd, with the modest beginnings of its now great fleet, and in 1861 the French Corapagnie Transatlantique. In 1863 the National line was established; in 1866 the Williams & Guion (now the Guion), which had previously existed as a line of sailing-packets; and in 1870 the White Star.

These are those in which we are most interested, as they touch our shores; but in the interval other lines were directed to all parts of the world, few seaports remaining, of however little importance, or lying however far from civilization, that cannot now be reached by regular steam communication.