Ship Tonnage Explained: Deadweight, Gross, Net, Displacement & Cargo Tonnage Defined

Confused by ship tonnage? This 1920 guide explains the five major types of ship tonnage—Deadweight, Gross, Net, Displacement, and Cargo—and how they impact trade, port fees, and ship design. A must-read for maritime historians, genealogists, and ship enthusiasts!

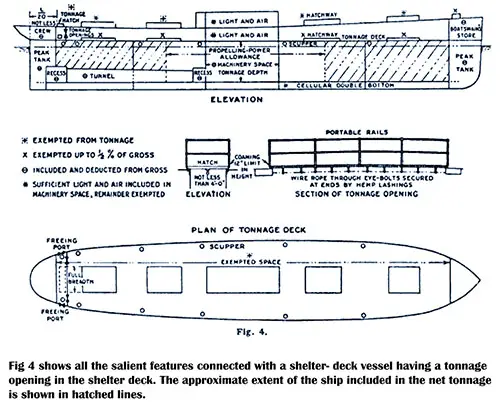

Plan of Tonnage Deck and Elevation for Measuring Tonnage of Ships. The Shipbuilder, May 1925. | GGA Image ID # 22088baf12. Click to View a Larger Image.

There are five different kinds of tonnage. Ordinarily, three tonnage terms are commonly used in discussing shipping: deadweight tonnage, gross tonnage, and net tonnage. The other two kinds are displacement tonnage and cargo tonnage.

Deadweight Tonnage

Deadweight tonnage signifies the maximum weight of cargo, bunkers, consumable stores, and all weight, including passengers and crew, that a vessel carries when loaded to its deep-load line.

Deadweight tonnage is a term used interchangeably with deadweight carrying capacity. It is expressed in terms of the long ton of 2,240 pounds or the metric ton of 2,204.6 pounds.

Deadweight tonnage forms customary for charter rates on ocean-going vessels engaged on time charters. It is of particular application to cargo vessels carrying coal, iron, or other bulky commodities, enabling the ship's operator to know the maximum cargo weight that the ship can hold and thus determine the extent of loading.

Gross Tonnage

Gross tonnage is commonly used with merchant vessels and applies to vessels, not cargo. The official merchant marine statistics of the United States, Great Britain, and some other countries are published in gross tonnage.

In certain countries, gross tonnage is used as the basis for fixing ship subsidy payments. The term gross tonnage is held in official reports to express in units of 100 cubic feet the total cubical capacity of the vessel, including the spaces occupied by cabins, engines, boilers, and coal bunkers.

This book's chapter on Measurement and Tonnage Laws has itemized nine different spaces exempt under United States rules from gross tonnage measurement.

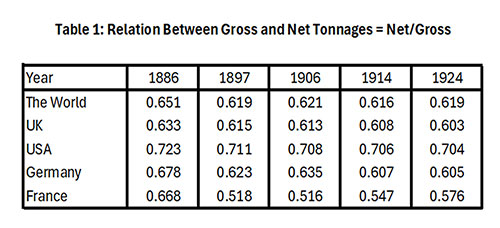

Tonnage Variations Across Countries: The Table Shows the Relationship Between Gross and Net Tonnage Computed by the UK, USA, Germany, France, and the World, Where Net Tonnage Is Divided by Gross Tonnage. Understanding This Relationship—Specifically, How Net Tonnage Is Derived From Gross Tonnage—Provides Valuable Insights Into the Efficiency and Capacity of Maritime Vessels. The Shipbuilder, May 1925. | GGA Image ID # 2208bac6c6

Net Tonnage

Net tonnage construes the net ton as equaling 100 cubic feet of carrying capacity, excluding deductions for space occupied by cabins, machinery, fuel, etc. Therefore, a vessel's gross tonnage minus certain deductions permitted by law and taken broadly signifies the amount of space available for the actual carrying capacity of cargo and passengers.

Net-register tonnage has been the basis for tonnage taxes and other tonnage dues worldwide. Towage, dockage, and wharfage charges are often based on net register tonnage.

The United States Customs House statistics of ship entrances and clearances and those of many other governments are reported regarding net-register tonnage. Canal tolls are widely based in part or wholly on net tonnage.

Estimating these different kinds of tonnages varies according to the type of ship. There is no arbitrary standard of measurement. To compute, for a one-type freighter, the deadweight tonnage from gross tonnage is multiplied by 1.6, which gives the deadweight tonnage. To calculate gross tonnage from deadweight tonnage, divide the deadweight tonnage by 1.6. One can give no precise rule for passenger and cargo-carrying ships in general.

Rules and usages vary in the computation of net tonnage from gross tonnage. Under the Suez Canal rules, the average deduction from gross tonnage in determining net tonnage has been about 28 or 29 percent.

Under the national measurement rules of Great Britain, which have differed from the Suez, the deduction has been about 39 percent and the same percentage under those of Germany. Norway has allowed 37 percent, Denmark 41 percent, and France 42 percent deduction. For the first year or so of the Panama Canal operation, the deduction was 30 percent.

In contrast, in the United States, where another official rule prevailed, the deduction was about 34 percent. On October 1, 1919, the House of Representatives passed a bill directing that in Panama Canal, tolls rules of measurement based on the actual earning capacity of a vessel instead of net tonnage. The proposed regulations will likely cover deck cargoes as well as other cargoes.

There is no uniformity in tonnage among the world's different nations reporting on their merchant marine. Some countries give statistics of gross tons. Others report in net tons. This diversity needs to be clarified for comparative statistics. Shipping men believe an international standard is advisable to ensure better understanding and accuracy in the world's tonnage returns.

Displacement Tonnage

Displacement tonnage signifies the weight of a vessel, in tons of 2,240 pounds, and is equal to the weight of water the ship displaces. A merchant vessel's displacement "light" usually means its weight with its crew and supplies before any fuel, stores, cargo, or passengers have been taken aboard.

Displacement "loaded" is the vessel's weight, including cargo, fuel, and stores, and when fully loaded to its maximum deep-load line. "Actual" displacement is the vessel's weight when loaded to any draft. The term displacement tonnage is familiar because of its typical application to war vessels.

Cargo Tonnage

Cargo tonnage means the various forms of cargo tons and tonnage expressing the quantity of cargo and cargo capacity on an ocean-going vessel. Cargo tonnage may be recorded either in weight or measurement tons. In the United States and British countries, a weight ton is the English long or gross ton of 2,240 pounds.

Countries that utilize the metric system adhere to a weight ton of 2,204.6 pounds. Although the short ton of 2,000 tons is commonly used on railroad freight shipments in the United States, the long ton is usually used in American overseas trade where goods are shipped as weight cargo.

However, a large amount of ocean freight is shipped not by weight but in units of measurement tons. A measurement ton is usually 40 cubic feet. "Measurement cargo" means light package freight, the quantity of which is computed in measurement tons.

Bibliography

Bankers Trust Company, “Chapter XXIX: Tonnage Definitions,” in America’s Merchant Marine: A Presentation of Its History and Development to Date with Chapters on Related Subjects, New York: Bankers Trust Company, 1920, pp. 236-239.

E. W. Blocksidge, Tonnage Legislation and its Application to the Measurement of Ships, Institution of Naval Architects, April 1925. Reprinted in The Shipbuilder, May 1925.

🚢 Understanding Ship Tonnage: A Guide for Maritime Historians, Genealogists, and Shipping Enthusiasts

📜 Recap & Summary: The Importance of Ship Tonnage in Maritime History & Trade

Tonnage is a fundamental yet complex aspect of maritime history, influencing everything from shipping regulations and port fees to naval engineering and cargo capacity.

This 1920 guide provides a deep dive into five different types of tonnage—Deadweight, Gross, Net, Displacement, and Cargo—explaining their significance in ocean travel, ship classification, and trade logistics.

For teachers and students, this article offers insights into historical trade routes, ship engineering, and international commerce. For genealogists, it provides context on ship manifests and migration records, helping to interpret passenger ship capacities. For maritime historians and ship enthusiasts, it explains how ships were classified, taxed, and measured according to different international laws.

🌊 Why This Article is Important for Different Audiences

📖 For Teachers & Students

- Real-World Math & Engineering Applications – Tonnage calculations explain how ships were built for optimal capacity and efficiency.

- Naval Architecture – A critical look at ship measurements and how tonnage influenced vessel designs.

- Maritime Economics – Understanding tonnage helps students learn about shipping costs, port fees, and taxation of ocean-going vessels.

🧬 For Genealogists & Passenger Researchers

- Interpreting Ship Manifests – Helps contextualize passenger lists by explaining how ships were measured for passenger and cargo space.

- Migration & Ocean Travel – Understanding tonnage gives insight into the scale of transatlantic migration and cargo transportation.

⚓ For Maritime Historians & Ship Enthusiasts

- Ship Design & Functionality – Explains why certain ships had different tonnages and what this meant for international shipping.

- Global Shipping Regulations – Highlights how different nations measured tonnage differently, impacting international trade.

- Port & Canal Tolls – Discusses how ship tonnage affected toll fees in places like the Panama and Suez Canals.

🚢 The Five Types of Ship Tonnage Explained

1️⃣ Deadweight Tonnage (DWT)

Measures the maximum carrying capacity of a ship, including:

✅ Cargo

✅ Fuel

✅ Supplies

✅ Passengers & Crew

Expressed in long tons (2,240 lbs) or metric tons (2,204.6 lbs).

Used for cargo ships and charter rates—especially for bulk goods like coal, grain, and iron.

2️⃣ Gross Tonnage (GT)

Measures a ship’s total enclosed space rather than its weight.

Includes cabins, engine rooms, cargo holds, and storage spaces.

Measured in units of 100 cubic feet per ton.

Important for maritime regulations, government records, and ship subsidy payments.

📌 🔍 Noteworthy Image: "Plan of Tonnage Deck and Elevation for Measuring Tonnage of Ships."

✅ Provides a visual representation of how ship tonnage is calculated.

✅ Useful for engineers, ship historians, and students studying naval architecture.

3️⃣ Net Tonnage (NT)

Net tonnage = Gross tonnage minus deductions for crew spaces, machinery, and fuel storage.

Represents the space available for cargo and passengers.

Used for:

✅ Port & canal tolls (e.g., Panama & Suez Canals)

✅ Taxation & trade regulations

✅ Dockage & wharfage fees

📌 🔍 Noteworthy Image: "Tonnage Variations Across Countries: The Relationship Between Gross and Net Tonnage."

✅ Highlights how different countries computed ship tonnage.

✅ Useful for understanding international shipping laws and their impact on global trade.

4️⃣ Displacement Tonnage

Measures the total weight of the water displaced by the ship.

Two types:

✅ Light displacement – Ship weight without cargo or fuel.

✅ Loaded displacement – Ship weight when fully loaded.

Mainly used for warships, naval vessels, and ship stability assessments.

5️⃣ Cargo Tonnage

Expresses the weight or volume of cargo a ship can carry.

Two measurement systems:

✅ Weight tons – 2,240 lbs per ton (UK/US) or 2,204.6 lbs (Metric).

✅ Measurement tons – Usually 40 cubic feet per ton.

Used for pricing and load planning for ocean freight transport.

📊 Variations in Tonnage Measurements & International Confusion

A key takeaway from this article is how different countries used different tonnage rules, leading to inconsistencies in international trade statistics.

🌎 Some nations report in gross tons, while others use net tons.

💰 Canal tolls (Suez & Panama) use unique tonnage calculations.

📜 Early 20th-century maritime laws varied significantly by country, affecting global commerce.

This lack of standardization created challenges for international trade and port regulations, which shipping companies had to navigate.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images & Diagrams

📐 "Plan of Tonnage Deck and Elevation for Measuring Tonnage of Ships"

✅ Illustrates how ship tonnage is measured using volume-based calculations.

✅ Essential for maritime engineering students and naval historians.

📊 "Tonnage Variations Across Countries"

✅ Explains differences in how ship tonnage was calculated globally.

✅ Useful for understanding maritime trade laws and shipping taxes.

🌎 Global Impact of Tonnage on Trade & Shipping

Understanding tonnage classifications helps contextualize historical maritime trade and modern global shipping operations.

📦 Cargo Efficiency – Ships were designed to maximize deadweight tonnage while staying within port limits.

💵 Economic Impact – A ship’s net tonnage affected port fees, fuel costs, and canal tolls.

⚓ Naval Architecture – Larger ships required careful weight distribution to maintain stability and fuel efficiency.

By breaking down how ships were classified and measured, this article serves as a vital historical resource for those studying ocean travel, trade, and naval engineering.

📚 Additional Reading & Resources

📖 "Cargo and Carrying Capacity of Ships" – How cargo space was optimized.

📖 "How a Ship’s Gross Tonnage is Computed" – The math behind ship measurement.

📖 "Net Tonnage of a Vessel and Its Computation" – Why net tonnage mattered for global trade laws.

These references provide further insight into the evolution of ship measurement techniques.

🔚 Final Thoughts: Why This Article is Essential

This detailed guide to ship tonnage provides a rare glimpse into early 20th-century maritime regulations and shipbuilding standards.

🌎 For historians – It explains how different nations classified ships, affecting global trade.

📜 For genealogists – Helps interpret ship passenger records and migration data.

🚢 For ship enthusiasts – Provides detailed insights into naval architecture and ocean travel.

This essential resource remains relevant today, helping researchers understand how ships were classified, taxed, and optimized for trade. 🌊⚓