Deadweight Tonnage: The Key to Ship Cargo Capacity & Global Trade Efficiency

What is deadweight tonnage & why does it matter? Learn how ships calculate cargo capacity, how freight rates are set, and how deadweight tonnage impacts canal tolls & global trade. Essential reading for maritime historians, engineers & ship enthusiasts!

White Star Liner Entering Gladstone Dock, 1927. | GGA Image ID # 220a4976af

Dead-Weight Tonnage (1913)

A vessel's dead-weight tonnage is the difference between the weight or displacement of the vessel when "light" and when loaded to its maximum authorized draft. It is the number of tons avoirdupois that the ship can carry of fuel, cargo, and passengers; it is the vessel's dead-weight capability, its carrying power.

The term dead-weight is also applied in commercial practice, to some extent, to the weight of coal and cargo actually aboard a ship at a given time. In this sense the dead-weight tonnage of a ship at any particular draft is the difference between its displacement "light" and its displacement at its actual draft.

Would it be wise to levy tolls either upon a ship's maximum dead-weight tonnage or upon the dead-weight of the fuel and lading actually aboard a vessel at the time of application for passage through the canal?

As an argument in favor of tolls upon maximum dead-weight tonnage, it is urged that charges based upon the ship's carrying power are placed upon the weight from which the owners of the ship may derive traffic revenues.

This argument is strengthened by the fact that the rates charged for the Use of chartered vessels—i. e., charter rates—are upon dead-weight tonnage and that, inasmuch as a large share of ocean freight is transported in chartered vessels, the commercial world is accustomed to charges based upon dead-weight tonnage.

Advantages of Dead-Weight Tonnage for Tolls

The advantages to be derived from making maximum dead-weight tonnage the basis of canal tolls are, however, more than offset by the objections to making that tonnage the unit of canal charges:

- Freight ships, especially those employed in the transportation of bulk cargoes, would be heavily taxed, because of their large carrying power, while passenger steamers having comparatively little dead-weight capability would be but lightly burdened with canal tolls. Unless the rates of toll were different for different types of ships, there would be relative injustice as among different classes of vessels.

- Even as between freight ships carrying different kinds of cargo the charges would be inequitable. The tolls payable would be largest for vessels loaded with the heaviest, and thus ordinarily the cheapest, commodities. Minerals, nitrate, lumber, grain, and other bulk commodities have large weight in comparison with value, and the canal tolls would fall most heavily upon the classes of commodities that ought to be most favored by the tolls.

If cargo were made the basis of tolls, articles which are shipped as package freight ought to be charged tolls not upon their weight but upon their measurement tonnage—40 cubic feet, instead of 2,240 pounds, being considered a ton.

This would probably not be practicable, but unless it were done the discrimination against heavy bulk cargoes would be unjust to the shippers of "dead weight freight." Carriers, moreover, would find tolls upon weight of cargo less desirable than charges upon space occupied by freight.

Would it be advisable to base Panama Canal tolls upon the actual weight carried by vessels using the canal? It would seem offhand that tolls upon the actual weight borne by the vessel would be on a proper and desirable basis. Ocean carriers would thus be called upon, to pay charges for the use of the canal varying with the amounts transported through the waterway.

The tolls would not be placed upon the vessel, but upon what is in the ship, and would be made to vary with the weight of the vessel's burden. Moreover, the tonnage upon which tolls were payable could theoretically be obtained without difficulty.

It would be necessary only to read off from the vessel's displacement or dead-weight scale the difference between the ship's "light" displacement and its actual displacement at the time of passing through the canal.

As a matter of fact, however, the objections to tolls based upon the actual weight carried by vessels are stronger than the merits of such a system of charges.

There are the same practical and equitable reasons against making actual dead-weight carried the basis of canal charges as there are against the maximum dead-weight tonnage as a basis for tolls.

There would be the same difficulty encountered in deciding what should be considered the "light" draft of a vessel and thus what should be taken to be its "light" displacement.

Likewise there would be the same inequity of charges as among different types of ships and as between similar ships carrying different kinds of cargo.

Deadweight Tonnage (1928)

The total carrying capacity of a merchant vessel is sometimes expressed in terms of its deadweight tonnage, which represents the maximum weight of cargo, passengers, and fuel it can carry when loaded to its deep-load line. It is the difference between the vessel's displacement light and its displacement loaded.

The actual dead weight on board at any given time will, of course, vary from voyage to voyage but can be readily determined with substantial accuracy from the displacement curve and scale mentioned in connection with displacement tonnage.

This practical method of determining deadweight tonnage provides the captain with a reliable tool for managing the vessel's cargo capacity. Knowing the draft to which his vessel is loaded, the captain can read the dead weight on board from the curve and scale prepared when the vessel is constructed.

Deadweight tonnage, expressed in either the long ton of 2,240 pounds or the metric ton of 2,204.62 pounds, is the usual basis for the charter rates paid when cargo-carrying vessels are operated on time charters.

This key metric plays a crucial role in the economic aspects of maritime operations, influencing the rates and profitability of vessel operations. It is also of use in the loading and transportation, in vessel-load lots, of certain heavy, bulky commodities, such as coal and iron ore, and in the construction of vessels designed for such services; for knowing the amount of fuel needed to operate over a particular route, the deadweight tonnage discloses to the master of the vessel its net cargo capacity, or the maximum weight of cargo that may be shipped.

It is sometimes used as a statistical unit to record the size of a steamship company's cargo-carrying fleet or a government agency such as the United States Shipping Board.

The term deadweight tonnage is ordinarily not used in the shipping industry in connection with express steamers and combination passenger and freight vessels, for vessels of that type are rarely loaded to their deep-load line.

The prime consideration at the time of their construction is seldom attaining maximum capacity for heavy or deadweight commodities.

Bibliography

Johnson, Emory Richard, Measurement of Vessels for the Panama Canal, Volume 2, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1913, Pages 39-40

Emory R. Johnson, Ph.d., Sc.D., Grover G. Huebner, Ph.D., G. Lloyd Wilson, Ph.D., "Chapter XLII: TheMeasurement of Vessels and Traffic: Deadweight Tonnage," in Principles of Transportation, New York-London: D. Appleton and Company, 1928, pp. 488-489.

⚓ Deadweight Tonnage: The Backbone of Maritime Trade & Cargo Capacity 📦🚢

📜 Recap & Summary: Understanding Deadweight Tonnage and Its Role in Global Shipping

The articles "Deadweight Tonnage" (1913 and 1928) provide a detailed exploration of one of the most essential measurements in shipping—deadweight tonnage (DWT). Unlike displacement tonnage, which measures the total weight of a ship, deadweight tonnage calculates how much a vessel can carry, including cargo, fuel, and passengers.

This article is particularly useful for teachers, students, genealogists, maritime historians, naval architects, and shipping professionals as it explains how deadweight tonnage is calculated, how it impacts international trade, and why it is a critical metric in maritime economics.

💡 Key Takeaway: Deadweight tonnage directly influences a ship's commercial efficiency, charter rates, and canal tolls, making it one of the most crucial measurements in global shipping.

📊 Key Topics Covered: The Science of Cargo Capacity & Commercial Shipping

1️⃣ What Is Deadweight Tonnage (DWT)? Why Is It Important?

Deadweight tonnage (DWT) is the difference between a ship’s "light" displacement (empty weight) and "loaded" displacement (fully loaded weight).

This number represents the ship’s carrying capacity, including:

✅ Cargo 🏗️

✅ Fuel ⛽

✅ Passengers & Crew Supplies 🛳️

DWT is expressed in long tons (2,240 lbs) or metric tons (2,204.62 lbs).

🔍 Why It’s Important:

✅ Determines how much a ship can safely carry without exceeding its maximum draft.

✅ Used to set charter rates—most cargo ships are leased based on deadweight tonnage.

✅ Essential for canal tolls & port fees—as seen in Panama and Suez Canal charges.

2️⃣ Deadweight Tonnage in Commercial Shipping: Setting Charter Rates & Freight Costs

💰 Deadweight Tonnage = Profitability in Shipping!

- When ships are chartered (rented), charter rates are based on DWT rather than volume-based measurements like gross tonnage.

- This ensures that shipowners charge based on how much cargo can be carried, not just the ship’s size.

- Bulk cargo like coal, iron ore, and grain is transported using DWT-based pricing.

📦 Example:

A bulk freighter with a deadweight tonnage of 50,000 tons can be leased at a rate per ton per day.

If the rate is $5 per ton/day, the daily lease price would be $250,000.

🔍 Why It’s Important: Maritime businesses, investors, and government agencies track DWT to measure global trade volume and industry trends.

3️⃣ Deadweight Tonnage & Canal Tolls: How It Affects Shipping Costs

🚢 Should canal tolls be based on DWT?

This article discusses the debate over how tolls should be calculated for ships passing through international canals (e.g., Panama and Suez Canals).

Two Proposed Methods:

✅ Toll Based on Maximum DWT: Charges based on total cargo capacity, regardless of actual load.

✅ Toll Based on Actual Weight Onboard: Charges based on how much cargo a ship is carrying at the time of passage.

📉 Issues With Charging by Deadweight Tonnage:

❌ Unfair to bulk carriers (e.g., coal, grain, iron ore) which would pay higher tolls than high-value, low-weight cargo ships.

❌ Passenger ships would pay less even though they take up the same canal space.

❌ Difficult to verify "light" displacement—since ships lose weight as fuel is burned and cargo is consumed.

🔍 Why It’s Important: This debate is ongoing in global shipping as ports and canal authorities seek fair toll structures for all ship types.

4️⃣ Noteworthy Example: The White Star Liner at Gladstone Dock (1927) 🌊

📸 Key Image: "White Star Liner Entering Gladstone Dock, 1927"

✅ Captures a historic moment in maritime trade.

✅ Showcases a large passenger liner with significant deadweight tonnage but lower cargo capacity than bulk carriers.

✅ Illustrates how deadweight tonnage varied between ocean liners and cargo freighters.

🔍 Why It’s Important: A visual representation of how different ship types manage weight and cargo capacity.

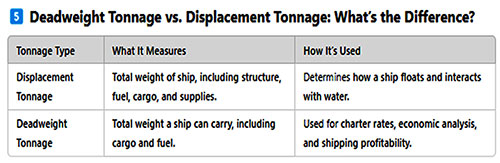

5️⃣ Deadweight Tonnage vs. Displacement Tonnage: What’s the Difference?

💡 Key Takeaway:

📦 Displacement tonnage tells us how much a ship weighs, while deadweight tonnage tells us how much a ship can carry.

🌎 Global Impact of Deadweight Tonnage in Maritime Operations

📦 Global Trade & Shipping Economics – DWT is the primary measurement for shipping contracts & freight rates.

🚢 Naval Architecture & Shipbuilding – Used to design vessels with optimal cargo-to-fuel ratios.

🌍 Canal & Port Fees – Essential for calculating tolls & taxation for vessels using international waterways.

📊 Government & Military Logistics – Nations measure fleet sizes in terms of total DWT to track shipping capacity.

By understanding deadweight tonnage, maritime professionals, historians, and economists can assess the efficiency, profitability, and trade impact of different vessels.

📸 Noteworthy Images & Their Importance

🖼️ "White Star Liner Entering Gladstone Dock, 1927"

✅ Illustrates the difference between cargo and passenger ship capacities.

✅ Highlights how deadweight tonnage is visually evident in ship design.

✅ Shows a famous historic ship in operation, making it valuable for historians & genealogists.

📚 Additional Reading & Resources

📖 "How A Ship’s Gross Tonnage Is Computed" – Explains how ships are measured by internal volume.

📖 "Displacement Tonnage" – Details how ships are weighed in relation to the water they displace.

📖 "Cargo and Carrying Capacity of Ships" – Discusses how deadweight tonnage affects freight transport.

🔚 Final Thoughts: Why This Article Matters

Understanding deadweight tonnage is key to deciphering maritime history, global trade, and ship economics.

🌎 For historians – Helps analyze historical shipping records & famous liners.

📜 For genealogists – Explains why some passenger ships had lower cargo capacities.

🚢 For ship enthusiasts – Provides a deep dive into the science of cargo weight & ship efficiency.

📦 For trade professionals – Clarifies why shipping costs & tolls are structured around DWT.

By mastering deadweight tonnage, we gain a deeper understanding of how ships transport goods, passengers, and fuel across the world’s oceans. 🌊⚓