Ship Tonnage Explained: Displacement, Deadweight, Gross & Net Tonnage Demystified

Confused by ship tonnage measurements? This 1932 guide explains the five major types of ship tonnage—Displacement, Deadweight, Cargo, Gross, and Net—used in maritime trade. Learn how tonnage affects ship design, cargo capacity, and port fees in this essential resource for maritime historians, genealogists, and ship enthusiasts.

Everyone who has looked at specifications for steamships is often bewildered by the many different tonnages used for the same vessel.

An ocean liner may have different gross tonnage, depending on which country's rules were used in determining the weight.

Below is an article from 1932 that provides a good explanation on just what the tonnages for ships really are.

There are five kinds of tonnage in use in the shipping business.

They are:

- Deadweight,

- Cargo,

- Gross,

- Net and

- Displacement Tonnages

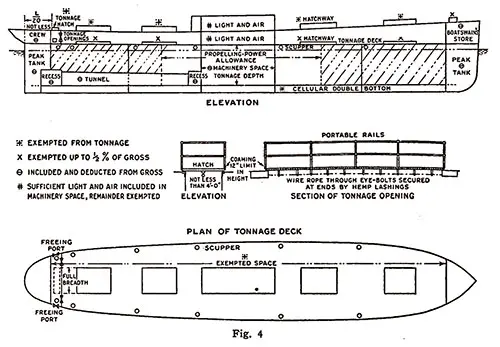

Plan of Tonnage Deck and Elevation for Measuring Tonnage of Ships. E. W. Blocksidge in a Paper Read at the Spring Meetings of the Sixty-Sixth Session of the Institution of Naval Architects, London, April 1925. | GGA Image ID # 1fe2d8613b. Click to View Larger Image.

Tonnage Defined

- Deadweight Tonnage: expresses the number of tons of 2,240 pounds that a vessel can transport of cargo, stores, and bunker fuel. It is the difference between the number of tons of water a vessel displaces "light" and the number of tons it displaces when submerged to the "load line." Deadweight tonnage is used interchangeably with deadweight carrying capacity. A vessel's capacity for weight cargo is less than its total deadweight tonnage.

- Cargo Tonnage: is either "weight" or "measurement." The weight ton in the United States and in British countries is the English long or gross ton of 2,240 pounds. In France and other countries having the metric system a weight ton is 2,204.6 pounds. A "measurement" ton is usually 40 cubic feet, but in some instances a larger number of cubic feet is taken for a ton. Most ocean package freight is taken at weight or measurement (W/M) ship's option.

- Gross Tonnage: applies to vessels, not to cargo. It is determined by dividing by 100 the contents, in cubic feet, of the vessel's closed-in spaces. A vessel ton is 100 cubic feet. The register of a vessel states both gross and net tonnage.

- Net Tonnage: is a vessel's gross tonnage minus deductions of space occupied by accommodations for crew, by machinery, for navigation, by the engine room and fuel. A vessel's net tonnage expresses the space available for the accommodation of passengers and the stowage of cargo. A ton of cargo in most instances occupies less than 100 cubic feet; hence the vessel's cargo tonnage may exceed its net tonnage, and, indeed, the tonnage of cargo carried is usually greater than the gross tonnage.

- Displacement: of a vessel is the weight, in tons of 2,240 pounds, of the vessel and its contents. Displacement "light" is the weight of the vessel without stores, bunker fuel, or cargo. Displacement "loaded" is the weight of the vessel plus cargo, fuel, and stores.

For a modern freight steamer the following relative tonnage figures would ordinarily be approximately correct:

- Net tonnage 4,000

- Gross tonnage 6,000

- Deadweight carrying capacity 10,000

- Displacement, loaded, about 13,350

Registered Tonnage

A vessel's registered tonnage, whether gross or net, is practically the same under the American rules and the British rules. When measured according to the Panama or Suez tonnage rules most vessels have larger gross and net tonnages than when measured by British or American national rules.

Bibliography

Article appearing in an American Export Lines Passenger List from June 28, 1932.

Illustration Fig. 4: E. W. Blocksidge, "Tonnage Legislation and Its Application to Measurement of Ships," in Marine Engineering and Shipping Age, New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company, Vol. XXX, No. 6, June 1925, p. 347.

For a more detailed discussion on Ship Tonnage and related computations, see:

🚢 Understanding Ship Tonnage: A Comprehensive Guide for Historians, Genealogists, and Maritime Enthusiasts

📜 Recap & Summary: Deciphering the Mysteries of Ship Tonnage

Maritime history is filled with complex terminologies, and one of the most misunderstood yet essential aspects of ships is tonnage measurement. This 1932 article provides a clear and structured explanation of the different types of tonnage, demystifying a concept that has long puzzled ship enthusiasts, historians, and those researching ocean travel.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and maritime historians, this guide serves as a valuable educational resource that clarifies how tonnage is measured, why it varies, and its impact on maritime operations. Whether studying historical shipping records, tracing passenger lists, or analyzing naval architecture, this article provides a deep dive into an essential topic in maritime studies.

🌊 Why This Article Matters for Different Audiences

📖 For Teachers & Students

- Primary Source from 1932 – A historical document that explains shipping terms still used today.

- Engineering & Math Applications – Tonnage calculations help students understand measurement, volume, and density in real-world applications.

- Navigation & Trade Implications – A practical look at how cargo is transported and calculated across different maritime industries.

🧬 For Genealogists & Passenger Researchers

- Passenger Lists & Migration Records – Tonnage classifications explain how ships were measured and how many people they could carry.

- Ship Size Comparisons – Understanding gross tonnage can help contextualize migration journeys on different ocean liners.

⚓ For Maritime Historians & Ship Enthusiasts

- Ship Construction & Design – Tonnage is one of the most crucial aspects of shipbuilding, affecting everything from size to carrying capacity.

- Global Trade & Port Regulations – The article discusses how different countries measured tonnage, impacting international shipping regulations.

- Historic Ship Specifications – The explanation of tonnage types provides insight into early 20th-century ocean liners and cargo ships.

🚢 Key Takeaways: The Five Types of Tonnage

The article breaks down five different types of tonnage, explaining how each is calculated and used in shipping operations.

1️⃣ Deadweight Tonnage (DWT)

- Measures a ship’s carrying capacity for cargo, fuel, crew, and supplies.

- It is the difference between the weight of the vessel when empty ("light displacement") and when fully loaded ("loaded displacement").

2️⃣ Cargo Tonnage

- Can be measured by weight (in tons) or volume (in cubic feet).

- Weight ton: 2,240 pounds in the UK/US, 2,204.6 pounds in metric countries.

- Measurement ton: Often 40 cubic feet, but varies by region.

3️⃣ Gross Tonnage (GT)

- Measures the total volume of a ship's enclosed spaces, divided by 100 cubic feet per ton.

- Important for port fees and ship classification rather than weight capacity.

4️⃣ Net Tonnage (NT)

- Gross tonnage minus deductions for spaces used by the crew, navigation, and machinery.

- Represents usable space for passengers and cargo.

- A ship’s cargo tonnage can exceed net tonnage, as cargo is denser than 100 cubic feet per ton.

5️⃣ Displacement Tonnage

Represents the actual weight of the ship and its contents, measured in long tons (2,240 lbs each).

Two forms:

Light displacement – The weight of the empty ship.

Loaded displacement – The weight of the ship when fully loaded.

📊 Example of a Typical Freight Steamer

A modern (1932-era) freight steamer would have approximately:

✅ Net tonnage: 4,000 tons

✅ Gross tonnage: 6,000 tons

✅ Deadweight carrying capacity: 10,000 tons

✅ Loaded displacement: 13,350 tons

This breakdown shows how ships can have vastly different tonnage measurements, depending on the calculation method used.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images & Diagrams

📐 "Plan of Tonnage Deck and Elevation for Measuring Tonnage of Ships"

- A technical illustration showing how tonnage measurements are applied to ships.

- Useful for naval architecture students, maritime engineers, and ship historians.

⚖️ "Registered Tonnage & Measurement Differences"

- Comparative charts explain how different countries (UK, US, Panama, and Suez) measure tonnage differently.

- Highlights how the same ship can have multiple official tonnage values.

🌎 The Global Impact of Tonnage Regulations

One of the most fascinating takeaways from this article is how tonnage measurement differs by country and affects global shipping laws.

- Panama & Suez Tonnage Rules – Ships often have larger official tonnages under these systems, which influences canal tolls and fees.

- British vs. American Rules – Though similar, small variations exist in how spaces are deducted from gross tonnage.

- International Trade & Port Fees – A ship’s tonnage classification directly impacts its operating costs, affecting everything from fuel efficiency to docking fees.

This complex regulatory landscape is crucial for anyone studying shipping economics, international trade, or maritime law.

📚 Additional Reading & Resources

For those wanting to dive deeper into historical ship tonnage and its real-world applications, the article references the following resources:

📖 "Cargo and Carrying Capacity of Ships" – Explores how ships maximize cargo efficiency.

📖 "How a Ship’s Gross Tonnage is Computed" – A technical guide on volume-based tonnage calculations.

📖 "Net Tonnage of a Vessel and Its Computation" – Examines how net tonnage affects passenger and cargo transport.

These readings provide additional context for those studying shipbuilding, naval architecture, or historical maritime regulations.

🔚 Final Thoughts: Why This Article is Essential

This 1932 guide to ship tonnage is more than just a technical explanation—it is a historical document that captures the evolution of maritime measurement and regulation.

🌎 For historians – It provides insight into early 20th-century maritime law and global trade.

📜 For genealogists – Understanding tonnage helps contextualize ship records and migration history.

🚢 For ship enthusiasts – It serves as a foundational guide to naval architecture and ocean travel.

📚 For educators – It is an excellent teaching tool for STEM subjects, maritime economics, and history.

By breaking down complex shipping measurements, this article remains a timeless resource for anyone passionate about the history of ships and ocean travel. 🌊⚓