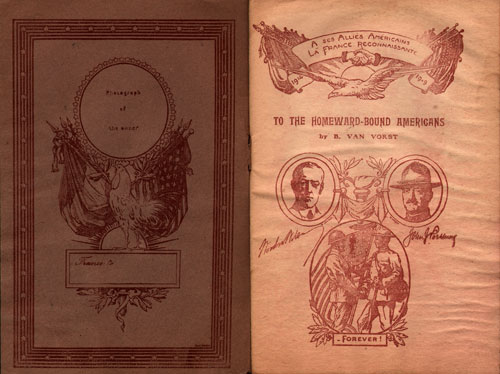

To The Homeward Bound Americans - 1919

First Panel, To the Homeward-Bound Americans by B. Van Vorst. © 1919. GGA Image ID # 19c493fc6e

This 1919 Booklet "To The Homeward Bound Americans" by B. Van Vorst, Printed in France, provides an excellent recap of the activities of the Allied Expeditionary Force (A. E. F.) and their activities in France.

Introduction

You are about to embark for the United States as the homeward-bound soldiers of the first American Expeditionary Forces, whichever crossed the seas to fight on foreign soil.

At the moment of your leave-taking, it is the purpose of this little book to state in a few words what your presence has meant to the French people, to express to you their gratitude, and to recount briefly the part you played in winning the war.

At the most critical moment of the struggle, which had lasted for three years against German imperialism, you came as strong youths into a country where the young had perished.

To the weeping, you brought a smile, to those who had been despoiled, your generosity restored hope, to the fatherless children you offered joy. The summing up of these recollections must remain an inspiration to you and to those who follow you in all future efforts.

Often, marching toward dusk, along some valley road in France, you have watched the lights as they began to shine out from the windows of the little farmhouses.

At the same time, the mists gradually enveloped all but the shadowy forms of objects, almost indistinguishable. Let it be so in your minds when you think of France: remember the innumerable small homes which nearly two million men have died to save, and those hearths where a fire still burns, though the poilu who left it will never return.

If any harsh thoughts remain, let the mists enfold all that is not the romance of this war — the drawing together in fraternal love of those who have suffered. This is the prayer of France.

Together with the gratitude of her living, there is the stirring memory of her dead. It carries its message to you, as a blessing from those who, because of your heroic sacrifice, shall not have given their lives in vain.

The Americans Arrive in Paris

Early in February 1915, the Kaiser made his first tyrannical assertion concerning where he would allow the ships of his enemies and neutrals to pass without German submarines.

In less than a week, President Wilson had protested. His first note declared that he would hold the Kaiser to account if the Germans sank one American ship or one American life taken. The details of the discussion which ensued are present to the minds of all.

The point maintained by the American Government was that citizens of the United States had the right to travel by sea, where and whenever they pleased, on American, neutral or belligerent ships.

To this proclamation, the Kaiser continued to make evasive answers. In the spring of 1916, after the attack on the Sussex, he promised to modify his illicit attitude.

But on 31 January 1917, with his customary bad faith, he declared that all ships attempting to approach the English or Irish coast, or any port in the Mediterranean, would be sunk without warning.

Within forty-eight hours, the United States had broken off diplomatic relations with Germany. On 6 April 1917, war was declared by the United States. This was the most extraordinary event since the Battle of the Marne.

It meant that German imperialism was to be conquered. America had taken her place definitively on the side of democracy and liberty, which she valued more than prosperity and peace. She was going to fight because she did not intend to become German.

Already, before this, the idealism of Americans had begun to be felt among the Allies. The gallant conduct on the battlefield of the vanguard of volunteers, the disinterested generosity of the Ambulance units, the Red Cross workers, the members of the American Fund for French Wounded, and many others had revealed the fine American spirit of true brotherly love. Charity, however, was one thing, and the war was quite another.

It was known that the United States had only a small standing army and no regular system of military service. England had not been able to vote conscription until seventeen months after the war began.

How was America to recruit soldiers, and what sort of soldiers would they prove, under the baptism of fire? These were the questions the Allies and even Americans asked.

Within a week after the United States had declared war, France had dispatched to America a Mission which included the Minister of Justice, Mr. Viviani, Maréchal Joffre, Admiral Chocheprat, and the Marquis de Chambrun, followed almost immediately by a French High Commissioner, Mr. André Tardieu, who devoted himself to establishing in Washington a well organized and harmonious collaboration between the two countries.

The victory of the Marne, and the sufferings of France, were personified for Americans in the presence among them of Joffre. The welcome he received was a national demonstration; it rang out with glory from hearts full to overflowing with compassion and gratitude.

Congress almost immediately voted conscription. The popular response to this act brought, in a fortnight, over ten million enlistments to the recruiting bureaux. Time and space, no doubt, seemed to rise up as two massive obstacles to any very successful military effort on the part of the United States.

Yet, a feeling of moral comfort began to permeate the atmosphere, not only of the fighting forces but also of civilians. Russia had gone to pieces, but America had taken her place in line with the Allies.

So, in June 1917, when General Pershing arrived in Paris with the first contingent of the Expeditionary Forces, there were crowds in the streets and about the station to meet him and to acclaim the American soldiers.

The cheers went up like a cry of relief, and when the French saw the smile which answered them, the smile of youth, happy and glad to lend a hand, to lay down as many lives as need be, then the welcome became more personal, a note of instinctive sympathy sounded in the greeting.

From sympathy, the feeling grew to one of respect on the day when General Pershing, standing over the grave of the French General who, in 1776, had helped the United States win her freedom, echoed the lasting gratitude of the American people and pledged the future, in these few words:

"Lafayette, we are here."

That day the four walls of the Invalides resounded to the strains of an American military band. Joffre stood beside Pershing in the courtyard of the historic building.

Poincaré was there, and the descendants of Rochambeau and Lafayette. Flanked by the bolus, tried in battle, alert and resolute, the American soldiers of this first division marched out to meet their fate.

This time it was love that greeted them on their way; women and girls broke up the ranks more than once to embrace these soldiers. From the windows under which they passed, roses were showered down upon them.

When they reached the Hotel de Ville, they looked like a moving garden with flowers in their belts, in their hats, in the barrels of their rifles.

More appealing still was the spontaneous enthusiasm of the children. The first column of American soldiers as it swayed along at a brisk marching pace, was accompanied by a procession of little people, the lonely little people of France who had seen their fathers, their brothers go out to battle, never to return, and who now clung to the hands of these strong youths from over the seas, with touching confidence.

These were the men they had watched in the "cinemas," they had read about them in books on the Far West, their present was a dream come true. That first day the children seemed to be leading the American soldiers, showing them to Paris, with pride, as if to say:

'They've come, you see. They are our friends. Now we are safe."

One little girl, asked if she would sell her American flag, even when offered as large a price as three dollars, stoutly refused.

"It is not the flag I cannot sell," she said, "it is my heart."

Nor were their hopes too high. As the Americans increased in numbers and spread out in every direction, waiting to fight, their kindness and generosity became generally known. Speaking of Tours, where many of the troops were quartered, one little, old French woman said:

"We have no more poor in our town. The children and the old people are always with the Americans now, and they are all laughing together."

Another day, in a more remote part of the country, a farm goes up in flames. Immediately the Americans organize an amateur brigade. When the fire is put out, they pass around the hat and take up a collection of one hundred and fifty dollars to help pay for damages.

"We were so choked," the farmer said, "that we could not even speak."

So the Americans, training for war, went about doing kind deeds. Then, at last, came the call to fight.

The Service of Supplies

The most significant difference and gratitude are due to General Pershing for his far-sighted judgment in planning at once an organization sufficiently vast to accommodate the army, which his military genius realized would be needed to "turn the scale in favor of the Allies."

The task of preparation to be accomplished was formidable. In the opinion of the Commander-in-Chief, the "immensity of the problem could hardly be overestimated."

Three thousand miles of the sea stretched between the most easterly ports of the United States and the most westerly harbors of France. The best of these, in the north, were crowded by the shipping and supplies of the British Armies.

Further down the coast, Saint-Nazaire, Bordeaux, Nantes, La Pallice, while comparatively free, had insufficient facilities for handling the quantities of material and caring for the numbers of men to be brought across the Atlantic.

Working against all manner of difficulties, in a country which, for over three years, had been devastated by war, the S. O. S. and Engineer contingents built docks, by the mile, they constructed buildings which, if strung out, end to end, would cover a distance of 452 miles, they set up 1,055 locomotives and 14,302 cars sent from the United States, and, for the French, they mended 1,423 locomotives and 45,993 cars.

They laid 1,475 miles of railway and stretched through the air 125,000 miles of telegraph and telephone wire. They handled 129,143,188 objects of clothing.

They provided bakeries that averaged an output of almost two million pounds of bread a day. When the armistice was signed, the Transportation Service was operating in thirty ports. Under American supervision, on the piers seemed to have sprung up in a night, over five million tons of material had been unloaded.

One hundred thirty-five men broke the record of the first company of Railway Engineers to arrive in France. They laid 2.69 miles of narrow gauge railway in about 7 hours.

This meant handling 105 tons of steel rails, 1,830 pairs of plates, 7,100 ties, eight kegs of bolts, 37 kegs of spikes, a total of 230 tons in 433 minutes.

The German Imperial Government had believed it impossible that America could raise an army, equip it and transport it across an ocean beset with submarines which, during the same month when the United States declared war, had sunk 872,300 tons of allied and neutral vessels.

Between June 1917 and November 1918, over two million soldiers crossed the Atlantic. Owing to the convoying of ships, proposed by President Wilson, who, from the first, had proclaimed that America was ready to give her last cent and her last drop of blood, not one life was lost through aggression by the enemy.

America had accomplished a gigantic industrial triumph in history: she had dumbfounded the Germans who, throughout the world, were celebrated for their system of organization.

All this effort was made so quietly that no one knew what the Yankees were about. Yet, now that the war is won, the vast accumulation of war material has lost its significance.

What endures is the spirit in which the Americans worked. Their ingenuity in saving time and overcoming all obstacles will remain an example of what can be accomplished when the men of a free democracy labor together in fraternal unity for a common cause.

French Assistance

No less quiet and effective was how the French Government furthered the efforts of the Americans in procuring supplies. Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes, General Purchasing Agent, in his report, has given the following account of French collaboration:

"The demands of the A. E. F. for material in France "were tremendous and insistent. Approximately one-half "of the entire material and supplies used from the "beginning to the date of the armistice, to wit about "seven million tons, were secured in France.

"The thanks of our nation are due to the members of "the French Government. Not only did they assist in "every way in protecting the entire purchasing processes "of the A. E. F. from exorbitant prices, but they were "invaluable in their efforts to expedite the furnishing of "supplies from the French Government, and to uncover "new sources of supply in the open market."

"Whether in the early days we were seeking metal and "timber for primary construction, or whether in the "later days, in the Saint-Mihiel and the Argonne-Meuse "battles we were crying out for horses to take our "artillery into action, or for camions to transport our "troops, these men of the Haut Commissariat, with an "energy and devotion which knew no limit, found in "some way, the means to assist us and to enable us to "surmount acute crises. "

The proof of this cooperation lies in the fact that when the armistice was signed, all of the 75 mm guns, all of the 155 mm howitzers together with 65,000,000 shells which had been fired from them, 57% of the long-range guns and 81% of the airplanes in use by the A. E. F. had been supplied by the French.

It had been estimated that the American Army would need 15,000,000 tons of material. Only 9,000,000 tons were actually sent from the United States: the other 2/5 were procured in France.

General Dawes concludes his report with this tribute to the courage which prevailed behind the lines:

"France herself was largely stripped of military "supplies. Thus almost every cession to the American "Army meant a curtailment acutely felt by some portion "of the French people and their brave army.

The efforts "of the French cooperation remind us that it was not "upon the battlefield alone that Frenchmen and Americans were brothers in a common effort."

All That We Have

By March 1918, the period of waiting was almost at an end. Secretary of War Baker, after an inspection of all the work in France, declared:

"I find the boys in splendid condition and splendid spirits. I have been from the factory to the farm. Now I am on the frontier of freedom."

Everywhere he heard of the daring and the bravery of the American soldiers. Their praises were sung by the French officers who, both in the United States and in France, had assisted in their training.

Meanwhile, the Germans had brought up eighty-five fresh divisions and launched a formidable attack. By 25 March, they had driven the British back over the Somme.

Harn, Péronne, Combles were in the enemy's hands, who was only one hundred miles from Paris. The fighting in the French sector near Noyon was of unprecedented violence. The situation had become exceedingly serious.

On 28 March, two days after Foch had been made Generalissimo in supreme command of all the forces on the western front. General Pershing made him the following declaration:

"I have come to tell you that the American people would consider it a great honor for our troops to be engaged in the present battle. I ask you for this in their name and my own.

Infantry, artillery, airplanes, all that I have is yours. Use it as you wish. More will come in numbers equal to the requirement. I have come particularly to tell you that the American people will be proud to take part in the greatest and finest battle of history."

Cantigny

General Pershing, with the clear foresight which was one of the determining factors of the final victory, had insisted from the beginning upon the development of a "self-reliant infantry, thoroughly drilled in the use of the rifle and the tactics of open warfare."

He had reason to be proud when, on the morning of 28 May, the 1st Division went into action. On a front 2,000 yards wide, they pushed forward in less than a quarter of an hour to a depth of 1.800 feet.

They made 300 prisoners, they seized the village of Cantigny and all other objectives, and held them against severe counter-attacks.

Compared to the activities of the French and British, this combat, on a front extending from Verdun to the sea, was of minor importance.

The news of the brilliant dash with which it had been executed spread like wildfire. It was a revelation of what no one had dared to hope: the Americans were warriors. Their fighting spirit could not be surpassed.

Château-Thierry

The German offensive had meanwhile turned its fury upon the Aisne, with Paris as objective. Again every available man was placed at the disposal of Marechal Foch.

The 3rd Division, fresh from its preliminary training in the trenches, was rushed with all spread to the Marne. Its machine gun battalion, pushing ahead to meet this call, successfully held the bridgehead opposite Château-Thierry.

The French order of the day, referring to this action, reads:

"The courage of the Americans was beyond all praise. Though accustomed to acts of heroism, the Colonials themselves were struck by the excellent morale in the face of fire and the extraordinary cool-headedness of their Allies. The episode of Château-Thierry will remain as one of the brilliant pages of the war."

Bouresches, Belleau Wood, Vaux

The 2nd Division, which had been in reserve near Montdidier, was sent at the same time by every available means of transport to help in the effort at holding back the enemy, who with increasing forces was bearing down upon Paris.

On 6 June, against the best German guard divisions, the Marines led a charge which, by midnight, had ended in the capture of the village and railroad station of Bouresches.

The next objective was Belleau Wood, a point of vital importance. In this attack, the conduct of the 4th Brigade of the 2nd Division was so brilliant, in combat with a numerous and ferocious enemy, that after the capture of Belleau Wood, the General commanding the 6th French Army decided it should henceforth be called "Marine Brigade Wood."

The French 6th Army cited the 3rd Brigade of Marines as having given a "superb example of dash, abnegation, and sacrifice" and as having taken an important part in the victorious attack which led to the evacuation of French territory and which forced the enemy to solicit an armistice.

Though the 2nd Division had been fighting steadily for over two weeks, it was able, before being relieved, to seize the village of Vaux, in an offensive so perfectly planned and carried out with such precision that it was described by the French as "destined to remain a model of its kind."

The Second Battle of the Marne

On 15 July, after a pause for reorganization, the enemy launched a formidable onslaught from Château- Thierry to the Argonne. It was to be the last.

Within forty-eight hours, the Allies had broken this offensive. The six American divisions thrown along the Marne did their large share in checking the German advance.

On 18 July, in the thrust toward Soissons, the place of honor was given to the 1st and 2nd American Divisions, in company with French troops chosen for their prestige on the battlefield.

By the first days of August, the Marne salient, into which the enemy had imprudently driven hundreds of thousands of his best troops, had been completely wiped out.

The French General, Mangin, who directed this offensive, when success had been attained, addressed as follows the American troops who had been under his command:

"You threw yourselves into the counter-offensive, and "your indomitable tenacity stopped the counter-attack. "I am grateful to you for the blood you have so generously shed on the soil of my country.

I am proud of "having commanded you during such splendid days, and "to have fought with you for the deliverance of the "world."

General Pershing in Command

On 10 August, the First Army was organized under the personal command of General Pershing.

Given the vital part the Americans were now to play, they needed to take over a permanent portion of the line, which extended from east of the Moselle River to a point near Verdun.

The operations in this sector resulted in signal success: on 12 September, the First Army wiped out the Saint-Mihiel salient, it released the inhabitants of many villages, took 16,000 prisoners, 443 guns, a significant quantity of material, and it established the new lines in a position to threaten Metz.

The power of the American Army had asserted itself. The gratitude of the French to the Commander-in-Chief was threefold: for his foresight in planning from the first for an army of millions, for his judgment in realizing that his soldiers must exercise themselves not in trenches, but in a war of movement, and for his character, so essentially American, which in the most critical moments laid aside all questions of personal vanity, in a disinterested determination that the cause, for which his men were giving their lives, should triumph.

The young American Army has been fortunate in possessing among its historians the great-grandson of Lafayette. In his American Army in the European Conflict, he relates the brilliant exploits of which he was himself a witness on 12 September. "They were," he writes, "inspiring for the men, the officers, and the chiefs of the entire Expeditionary Forces."

The Meuse Argonne Offensive

Twelve days later, hostilities were to be resumed on a much larger scale: at daybreak, on 26 September, a barrage fire which for eleven hours illuminated the sky announced that the American offensive had been launched, between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse river.

This battle—one of the most critical operations of the war—was to continue until the enemy capitulated. The objectives assigned to General Pershing's Army were of paramount importance.

The Germans realized that if they could not hold their line of communications at this point, all would be lost for them. They consequently withdrew division after division from the north to fling them in desperation against the Americans.

Out of nine divisions that took part in this brilliant attack, sustained for 47 days, only three were in possession of their organic artillery or had ever taken part in war activities.

Five divisions came in contact with their artillery for the first time on the battlefield. Two divisions had spent about sixty days in calm sectors. One had been ten, another sixteen days in the trenches. Two had never been under fire.

They were provided with three-quarters the regulation number of horses and wagons, and the natural difficulties they had to face seemed impossible.

Yet despite roads heavy with mud, deep ravines, thick woods, and steep hills, the Americans pushed steadily on. Not at any time superior in numbers to the enemy, they always had the upper hand during this long struggle.

On 26 October, at the end of the first month, the troops had made an average advance of 10 miles on a 20-mile front, they had freed 45 villages from the Argonne to the Meuse, they had liberated 200 square miles of territory, and they had penetrated the four strongest German systems of trenches, including the Hindenburg line. The aviators had shot down 230 airplanes and 20 balloons.

The gains from 1 November to 5 November brought the Americans to within 3 miles of the Metz-Sedan railroad, one of the two main lines connecting France with Germany. Five days "before the armistice was signed, Maréchal Foch sent General Pershing the following message:

"Operations since 1 November, by the First American Army, have already assured, thanks to the courage "of the High Command, and to the energy and the "bravery of the troops, results of the greatest importance. I am happy to offer you my warmest congratulations on the success of these operations."

Fifteen out of the twenty-two divisions engaged had been twice in action during the Meuse Argonne battle, in which the Americans sustained 100,000 casualties.

The Armistice

On 11 November 1918, an armistice was signed, the enemy had capitulated: the war was won.

The days when the Americans had fought the [Germans] with a will to beat him or die were followed by months of waiting. During this period, 6,000 officers end soldiers were able to follow courses at the French universities, while 10,000 attended the improvised American University of Beirne.

All the men of the A. E. F. had an opportunity to study and become better acquainted with the French people. France now asks them, in judging her, not to forget certain fundamental truths regarding the difficulties with which she has always had to contend and the place which she holds among the nations of the world.

Forty million people live in France, which covers an area smaller than that of Texas. Competition consequently is intense. The Frenchman who wants to succeed must-have, though it takes years to procure it, technical training and instruction in whatever branch of an industry he intends to make his specialty.

On the other hand, because of her natural riches — more significant than those of any country in Europe except Russia — France has been invaded by all of her neighbors since the beginning of her history.

To meet this constant menace of aggression, all young Frenchmen at the age of twenty have been obliged to leave their work and to spend a period varying from two to seven years in preparing to be soldiers at a pay of one cent a day to themselves and a cost to the Government of hundreds of millions a year.

The State indeed spends far more on public instruction and the upkeep of the army and the navy than on commerce and industry.

How much would such a situation affect the American mentality, the prosperity of the United States?

It determines the character of the French people in their business dealings and their choice of an occupation. Two out of every five of the inhabitants of France have something put away in the savings bank.

In 1913, all these contributions, including small accounts given as school prizes to children, amounted to over one thousand million dollars, or an average of about $30 a bead.

At the same time, the individual proprietors who own a piece of land, or a house, or both, number eight million.

This thrifty state of affairs results from the cautious manner in which the French people face existence: they are always ready for a possibly long period of war.

Recent history has proved the wisdom of their foretaught. Following the wholly unexpected invasion of the Germans in 1914, at a moment when the French have never been more pacific, more democratic in their national sentiment, the first war loan was over-subscribed forty times.

The last budget, called for in October 1918, after an enemy occupation which had endured four years forever, brought six thousand million dollars, or an average of $152 per inhabitant.

In 1871, when the Franco-Prussian conflict had drawn to a close, the Germans, hoping to crush the French, exacted from them an indemnity of one thousand million dollars.

They were at the end of a campaign during which Paris had been besieged for one hundred and thirty-one days before capitulating and which had been followed by a civil uprising.

They had changed their form of Government from an empire to a republic during the war, and they were beaten. Yet, they paid the indemnity out of their economies in seven months.

Thus, it is a national necessity for the French to prefer security to risk. Significant numbers of Frenchmen become government employees simply because, though poorly paid, they receive a small pension for life at the end of twenty-five years of service. Financiers, on the other hand, are scarce.

Credit is little practiced. The Banque de France, which has 500 branches throughout the country, has only 15,000 depositors who use a checkbook. The Credit Lyonnais counts 155,000 depositors, who draw checks to an average of only $1,200 a year.

The fact that for fifty-two months, a violent war was raging on French soil has somewhat emphasized this frugal attitude about money. It has led to a slight misunderstanding in the dealings with foreigners.

A better knowledge of the reasons for so close a reckoning of the pennies should help dispel unpleasant memories.

In France, millions of French soldiers and millions of overseas troops, English, Irish, Scotch, Indians, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Serbians, Russians in the beginning, and Americans later on, were concentrated in a relatively limited area.

There was also a constant stream of refugees pouring into the free part of France from Belgium, from the invaded districts, and Serbia.

In the meantime, 8,000,000 Frenchmen had been mobilized and taken from their regular work for national Defence, military and industrial. All these successive occurrences made prices go up as inevitably as the inflation of a balloon causes it to rise.

The increase in the United States calculated on forty-five different food, and industrial products amounted, in the first six months of 1918, to 210% on the one-time cost, while in France it soared to 384% on food, and 434% on manufactured materials.

This, you will say, is legitimate. You object to the temporary increase in the value of things, but the overcharge made, especially to American soldiers.

The same was the case in 1917 when the first large training camps were established in the United States.

Retrospectively considered, these commercial impositions lose their significance. You do not care now what price Lafayette and the French Expeditionary Forces paid for chickens in 1776.

You remember only that these men valued an ideal more than life. "Liberty or Death" were the words that appeared on their ragged shirts as they marched barefoot through the snow.

Their spirit, ever-living, urged you to take part in this war of principle, which because of your very disinterestedness, you have carried on to victory.

The French Woman

A country is as great as its women. The American girl, the citizen of a young, free-born people, unhampered by convention, generally seeks an independent line of action that develops her personality and which has surely furthered the progress of humanity.

The woman of France, a child of an older civilization, limits her influence to the family circle. She takes no direct share in public affairs. She is always part of a group whose first duty is the lending of mutual assistance.

The recognized purpose of existence for the French girl is that she should become a "wife and the mother of a citizen." All her short youth, therefore, she is preparing for the great adventure of life — marriage, which determines all worldly activity.

When the supreme moment arrives for choosing a life's companion, it is not the future bride herself but the older people who "arrange" the marriage. In this union, they recognize the culmination of a destiny.

They consider the natural aptitudes and tastes of those most intimately concerned, their family ties, health, wealth, and social position. So wise and practical, all of these matters might not be reflected upon if the girl were left to follow her own fancy.

So, wherever she appears, she is always accompanied by an older person. She may not go to a lecture or church alone, much less may she take her pleasures unattended.

Whatever the occasion, some relative is always present in whose mind one thought dominates — the future happiness of her charge, as a married woman.

Thus, the object of limiting the woman's independence is not to place her in an inferior position but to produce harmony in the family. In this deliberate association of two human beings with the hope of founding a home, money is very naturally considered.

At the time of marriage, a contract is drawn up: just as in business, both parties concerned assume their share of responsibility. The husband administers this common budget established by both.

However insignificant it may be, the fortune contributed by the woman is in the form of a dowry or dot, which her father constitutes for her as a token of material protection in return for her filial submission.

All these logical restrictions do not provoke the French woman. On the contrary, it would seem as though, having put money into this human enterprise, she was determined to make a success of it.

She never seeks a social position that might separate her from her husband: she works by his side, in the fields or the city. She makes his store her parlor, his friends her own, his interests and her ambitions one. Her joy is in her children and the unity of her household.

Because of this absorption of the French woman in. her family, foreigners have always found it difficult to become acquainted with her or penetrate the group of which she is the soul.

You soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces have had an unusual opportunity, .not to make friends as freely as in America, or to enjoy the comradeship which in France is unknown, but to see and study the French woman at the most critical moment of her history. During this war, the very homes she has given her life have been attacked and sullied by an evil enemy.

She has appeared to you as more than worthy of the burden laid upon her shoulders.

You have found her laborious, uncomplaining. Her abnegation has commanded your respect. You have seen her work with a sacred unity of purpose to keep up the courage and relieve the combatants' sufferings.

You have been amazed to note that with a broken heart and empty arms, she could struggle on to save others, forgetful of self, determined above all that her country should triumph.

Through all her trials and in her desolation, you have not heard her speak of sacrifice. Indeed, what has appealed to you most has been her grace in affliction, and at all times, her human tenderness.

If the poilus won the battle of the Marne, if at Verdun they would not let the Germans pass, it is because, behind the line, they were sustained by their obscure and glorious allies: the women of France. With toil and prayer, they helped to win the war.

What Other Countries Gave

Belgium has been the martyr of the war, Serbia has been the heroine. Belgium with only 7,500,000 inhabitants, with no standing army, only a national guard for Defence, supposedly protected by the treaty which respected her neutrality, and which Germany, with the other European nations, had signed, was invaded through bad faith and betrayal, and almost wholly occupied by the [Germans] from 4 August 1914, until the armistice was signed.

Serbia, with a population of 4,547,992, shared a similar fate. Except for a small region in the neighborhood of Monastir, she was entirely dominated by the enemy from 1915 until her successful advance in the autumn of 1918.

Aside from the soldiers killed on the battlefield, there were 50,000 deaths of typhus among the Serbian troops. At the same time, of the civilians, 700,000 were put out of existence, and thousands more were deported to Germany and Turkey's harems.

Italy, with characteristic gallantry, fought under the most trying geographical conditions. To storm the Austrian fortresses that commanded her frontier meant taking the offensive at an altitude of 10,000 feet, sometimes in snow ten feet deep, or again in mud or the rising spring freshets.

Though England was not obliged to endure the horrors of an enemy invasion, her sacrifices on land and sea were made with the determination inspired by a life-long tradition of freedom. The part played by the Colonies forms one of the stirring chapters of the war.

The British lost in ships sunk at sea 9,031,823 tons.

The story of Poland, all of which fell into the enemy's hands in 1915, is a series of disasters. The Poles suffered alternate destruction by the Russian armies in retreat or by the German and Austrian troops in advance, back and forth, until there remains nothing but a desolate waste of land devastated, animals that had been killed, and men who had died of starvation.

The Romanians were forced to endure a double humiliation: in 1916, the country was almost entirely possessed by the Germans, and in 1917, the patriots, being unable to assert their true spirit, the opposing political party made peace with the enemy.

The relative number of men from these countries who suffered or were killed are:

| Nations | Duration of Hostilities in Days | Casualties (Killed, MIA) | Wounded | Prisoners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 1,560 | 40,000 | 0 | 45,000 |

| France | 1,561 | 1,370,000 | 3,000,000 | 470,000 |

| Great Britain | 1,560 | 835,700 | 2,043,000 | 170,000 |

| Italy | 1,269 | 460,000 | 947,000 | 520,000 |

| Montenegro | 1,558 | 20,000 | 0 | 0 |

| Portugal | 1,450 | 1,406 | 5,207 | 0 |

| Romania | 558 | 150,000 | 0 | 200,000 |

| Serbia | 1,568 | 369,578 | 700,000 | 150,000 |

| United States | 585 | 88,000 | 179,625 | 2,900 |

As regards France, the following details may be added: Killed: 1,038,700 men, amongst whom 32,700 officers; died: 41,000 men; missing: 290,300 men, amongst whom 3,000 officers.

Amongst the prisoners (470,000) are included, 8,300 officers. Amongst the wounded (3,000,000), 734,000 men are maimed for life. The losses of France amount to about 26% of her mobilized men and 57% of her soldiers under 31 years of age.

What France Gave

During the summer of 1917, when the first American troops came to prepare to take part in the war, the French had already been fighting for thirty-seven months. They had lost, up to that time—killed, dead, hopelessly wounded, missing, and prisoners — 2,033,000 men.

Figures are impressive, yet the greater their number, the less one fails to grasp what they signify. To say that the Germans destroyed 1,500 French locomotives and 50,000 railway cars in the first days of the war, that later they sunk over a million tons of French ships, is a cold-blooded proposition.

But when you realize that fishing is one of the prosperous occupations in France, that Boulogne alone sells every year $5,000,000 worth of fish brought in by the nets off her coast, that out of the total of 78,000 fishermen, 31,000 have now lost their barks and find themselves with no means of earning a livelihood, you begin to wonder how their children and wives have managed to subsist during these long terrible months.

The invaded regions of northern France, although small in extent, were the wealthiest in the whole country, and they yearly contributed more than 20% of the French taxes.

One million agricultural implements have been destroyed in these departments; 36,000 horses, 1,700,000 head of cattle, 38,500 pigs, etc., have been killed or stolen by the enemy. Almost 40,000 acres planted in grain and 10,000 in pasture lands have been hopelessly torn to pieces.

The industries in this same locality, which have been wrecked, represent one-third of the total HP and one-half of the electric power in France.

The coal mines which furnished half of the coal and more than half of the coke used in France have been willfully flooded or blown up so that their production will not be normal again for several years.

The destruction of the iron mines reduces the French output by 80%, the steel by 85%. The textile industries have suffered in proportion: 94% of the linen spindles and 30 % of the cotton spindles are gone, not to speak of 500,000 flax spindles and almost 100,000 looms.

The breweries of the north—1,700 in number—the sugar refineries—220 in number—have been half-ruined. When the holocaust is added, the destruction of homes, furniture, works of art, and personal property, the total loss for these invaded regions, amounts to almost twenty thousand million dollars.

Such enumeration does not lay hold of your heart until you have seen, in a devastated village, some poor man, creeping back to what used to be his home, carrying with him a shovel or a pick-ax, in the hope of digging out something that resembles his former hearthstone.

The immensity of the desolation sweeps' over you when you catch sight of a middle-aged woman, in black, standing in the waste of ruins, destitute, broken-hearted, yet determined to begin life again.

Speaking of these brave and afflicted people, President Wilson, in his address to Congress, on 2 December 1918, said:

Their machinery has been destroyed or taken away. Their people are scattered, and many of their best workers are dead. If they are not in some special way assisted in rebuilding their factories and replacing their lost instruments of manufacture, others will take their markets.

They should not be left to the vicissitudes of the intense competition for material and industrial facilities, which is now to set in. I hope that Congress will not be unwilling, if it should be necessary, to grant some such agency as the War Trade Board the right to establish priorities of export and supply for the benefit of these people whom we have been so happy to assist in saving from the German terror.

Murder, theft, humiliation was part of the plan which the [Germans] were to execute. In opposition to this will of evil inspiration, it is uplifting to consider the spirit of the French people.

The fragment of a letter written in 1917 by a French woman from a northern town in possession of the enemy gives some idea of the situation. She says:

...But the material part is nothing to the agony we have had to endure due to women's military deportation by night... You can realize parents' state of mind seeing young girls of 16 to 20 going off amongst men of all conditions; no one knows where...We are in an atmosphere of misery. But, despite it, we keep up our courage and our confidence.

There are over half a million homes to be rebuilt in France.

Bear this in mind. Please think of the children who, on the day you arrived, placed their hands in yours, confident that you were their friends, that they might count on you in the future.

In helping them begin life again, you can offer them more .than material aid, if you teach them some of the lessons you have learned yourselves in free America, if you bring them, in their way of looking at things, a broader, because a more hopeful vision.