Hopes of the Hyphenated Immigrants in Steerage

The New York Detention Room

Preface

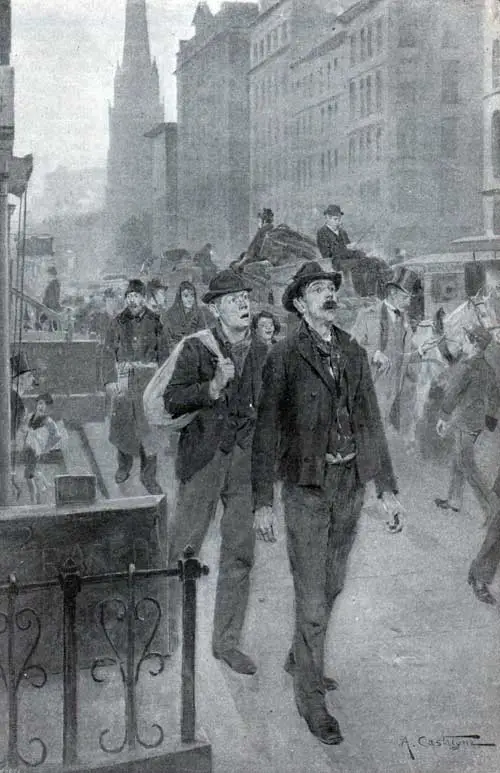

Another critical article is "The Hopes of the Hyphenated," by George Creel, who asserts that the persistent refusal of the "melting pot" to melt, as exhibited in the "hyphenated" question of the moment, is mostly the fault of our own Government and people.

He points out the vital necessity of a bureau of distribution, without which the arriving immigrant is totally unable to discover where he is most needed and ought to go, and becomes the victim of abnormal conditions which he in turn perpetuates. The illustrations are by A. Castalgne.

Hopes of the Hyphenated

WHATEVER else the hyphen may do, at least it is a thorn in the bed that has aroused the country to a realization of the imperative nature of the immigration problem.

In the activities of hyphenated societies and a foreign-language press, expressed by violent attacks upon the Government and hold disruptions of industry, there is clear evidence that the melting-pot has not been melting.

The bland assumption that we are one country and one people has been given a rude shock by bitter statistics filled with proof that great masses of aliens have failed to transfer their allegiance, a domestic peril that threatens the permanence of American institutions as gravely as any menace of a foreign foe.

The Slow Road To Citizenship

In the last decade, 1905 to 1914 inclusive, over ten million immigrants entered the United States with presumed intent to make this their home and the land of their devotion.

Three million returned to Europe after completing various terms of labor, and of the seven million immigrants remaining, only two and a half million have given formal evidence of any desire for citizenship.

Two-thirds of the seven million have never learned the English language with any degree of mastery, nor is the money earned by this army of foreigners invested in the United States or even deposited in American banks. In some years the amount sent abroad by aliens has reached a massive total of $300,000,000.

One third quitting the land that was to have been their home, two-thirds holding aloof from citizenship and common interest, two thirds unable or unwilling to learn the tongue of their adopted country, and the vast majority rushing their savings back to Europe! No record of failure was ever written so plainly.

At other times, when upheavals have developed the lack of a process of quick and wholesome assimilation, it has been the habit to put entire blame upon the ignorance, incapacity, and ingratitude of the alien, holding steadfastly that all fault is to be found in the material that comes to the melting-pot, and none in the pot itself. But is this true?

Can it be said that our treatment of the immigrant has been of a kind calculated to win his permanent allegiance or to convince him of the desirability of a complete Americanization?

On a day of the crisis, is it wise to cling to old prejudices in the face of new facts; in more understandable words, to save our face rather than to save American institutions?

The Immigrant's First Impression and Treatment

At almost every port of entry, the immigration buildings are old and inadequate, the equipment outgrew, and the working staff so small that inspecting officers have frequently been compelled to labor thirty-six hours without a rest.

As a first experience in the land of promise, aliens undergo detention in packed rooms and crowded hospitals, and wearisome delays exhaust health, strength, spirit, and money.

Eliminating the Hebrews, fully seventy-five percent of the immigrants come from the agricultural districts of Europe, yet a scant ten percent. ever reach the land in America.

The problem of employment presses heavily upon these new arrivals, for eighty-three percent have less than fifty dollars, and since the Government possesses no machinery of distribution, the starvation-scared immigrants make a rabbit rush for the nearest warren the moment the gates are opened.

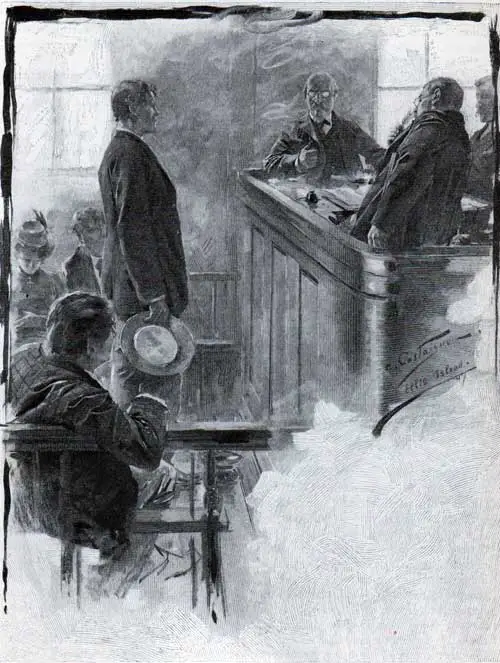

The Board of Special Inquiry, Ellis Island

Immigrant Laborers, Where Art Thou?

While the abundant acreage of the West lies idle for lack of labor, hundreds of thousands of farmers and farm-laborers are forced into the industrial centers of the East, adding to the congestion, dragging down the standard of living, and demoralizing the labor market generally.

In one year, while six thousand peasants were going to the fertile lands in Washington, Kansas, Oregon, Texas, South Dakota, Wyoming, Arizona, Idaho, and New Mexico, over two hundred thousand were herded into the mills and factories of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Illinois.

Ignorance and necessity drive them there, and ignorance and need to keep them there. Three-fourths of the immigrants in the United States has never been able to move away from the covert that first received them. The immigrants are rooted in the dead soil of isolation, poverty, and illiteracy, there is no hope of wholesome growth.

Employment Bureaus for the Immigrants

Just as the Government does not operate any agency of distribution, so is their lack of the protective machinery that might guard these bewildered strangers against the exploitations of the fake employment-bureau, the labor-agent, and the padrone.

Such as escape the tenements, the mill, or the mine, are huddled in remote construction-camps, where they live in filthy box-cars or vermin-ridden barracks, removed from churches and schools and without other recreation than the inevitable saloon.

Commissaries rob them, contractors cheat them, and even when they have sufficient courage to appeal to the law, attorneys' fees and court costs prevent them from prosecuting admittedly just claims.

The records of the labor-bureaus in the various States are thick with instances that prove it to be virtually a custom for a particular type of employer to take advantage of the ignorance and poverty of helpless aliens.

Much emphasis is laid upon the fact that the immigrants huddle in tenements, group by themselves in sordid colonies, and live in a fashion repulsive to American ideals. This is true enough.

The investigations of the Immigration Commission brought out the fact that fully one half of the alien population use all of their rooms as sleeping-rooms, and that the number of persons to a room runs as high as eight or ten. The slightest study, however, discloses the fact that this overcrowding is not due to inclination, but to economic necessity.

Difficulty Earning A Living Wage

The average annual earnings of a male alien total $385, quite obviously a sum that does not permit the maintenance of a family in a decent, sanitary environment. Women, forced into working to help the men, lend themselves even more readily to exploitation, two-thirds of them receiving less than $300 a year.

When wages are pooled, the resulting $685 still falls short of the $900 that federal experts have fixed upon as the annual amount necessary for the support of a family.

Since the wages of both man and woman are not sufficient to maintain an independent, self-respecting form of family life, the children are put to work, and the sleeping- and living-rooms of the house are packed with boarders so that the family income may be brought up to an existence level.

This low-wage scale is not so much due to lack of industry and capacity as to the alien's ignorance of the English language, and his consequent unfamiliarity with American methods and institutions. Not only this, but many immigrants cannot read or write even in their own language. The census report for 1910 showed that in the preceding ten years, 1,918,825 illiterates over the age of fourteen were admitted.

Literacy Amongst The Immigrants

Owing to compulsory education laws, the question of illiteracy is not one of great importance in the second generation; but what of the adult alien without the education upon which he must depend for protection and prosperity?

Little or nothing is done for him, and as a result, he huddles with those of his own nationality, remains the victim of padrones, and if he does become naturalized, it is at the instigation of some ward boss eager for the control of another vote.

Night schools, conducted by private organizations, are not the answer. After a day of drudgery, the mind of the immigrant reacts to the fatigue of the body, and as if this was not obstacle enough, these classes take no account of cultural, racial, and class differences.

Some of the aliens are bright, others stupid, some illiterate and others highly educated in their own tongue, but all are bundled into one group, with the result that the dull are discouraged and the educated disgusted.

Without knowledge of English, the alien is reluctant to leave his own people, unable to get a position in the skilled trades, barred from the unions, subjected to injustice and oppression, and forced into the monotonous drudgeries that break body and spirit.

Every survey yet made of immigrant colonies proves that increased earning power and the acquirement of English are quickly followed by better- homes, social ambition, and a more considerable civic interest.

The Ford increase in wages, for instance, resulted in an almost immediate improvement of living conditions, showing that the aliens were not huddling in tenements from choice.

Immigrants as Second Class Citizens

It is not only the case that America has been guilty of many sins of omission in connection with the immigrant, but there are also crimes of commission. The attitude of the average native-born American is one of superiority, contempt, and even hostility, making it difficult indeed for the immigrant to free himself from isolation or to gain direct contact with American life.

In the textile towns of New England, the factory districts of the Atlantic seaboard, and the various mining communities, the immigrants are forced into colonies and barred from participation in native affairs by a very definite wall of dislike and contempt.

Even the churches make a small effort to break down this barrier behind which the alien crouches, gazing silently at the land that has failed him in its promise of freedom and fraternity.

Because of these indisputable facts, is it possible to insist that the failure of the American melting pot is the fault of the alien entirely? If the hyphen persists as a menacing feature of American life, does the blame lie at the door of those expectant thousands who come to the United States in hope and faith or in the cruel neglects and exploitations that flow from the greed and indifference of the native-born?

It is a problem that must be faced, nor is there any likelihood that it will become less acute. The defeat of every attempt to establish a literacy test is proof conclusive that the American people are opposed to the restriction of immigration, and while the inrush of aliens will be checked during the progress of the European War, peace will witness their coming in more significant numbers.

History does not sustain any other prediction. The Napoleonic wars, the revolutions in Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and Germany, the Prussian campaigns against Denmark, Austria, and France, the Russo-Japanese War—all were followed by increased immigration to the United States.

Burdensome taxes, shattered families, ruined fields, and economic severities, the inevitable results of war, are bound to turn eyes to the one country that does not rest under the baneful shadow of militarism.

Neglect, Stupidity, and Oppression

The question for the United States to decide is whether the same old policy of neglect, stupidity, and oppression shall be pursued, or whether a new and sincere approach shall be made to the task of assimilation.

In this connection, let it be borne in mind that while the immigrant seems to suffer and die in seeming helplessness, he works his revenge upon society in a thousand ways.

Out of his ignorance and despair, he drags down the wage-scale, acts as a strike-breaker, lowers the American standard of living, and adds the note of actual ferocity to the competitive struggle.

Out of the slums where aliens fester in dirt and disease come the defectives and delinquents that fill our jails and asylums, and their ignorance and lack of public interest make them easy prey for the unclean political influences that prosper by municipal maladministration.

Ludlow, Calumet, Lawrence, Paterson, Cabin Creek, and other revolts of oppressed aliens have cost millions in actual loss and scarred whole States with hatred. Even if justice to the alien contains no appeal, there is the instinct of self-preservation to compel drastic changes.

The Immigrant Reform

Specific steps are already being taken in the direction of reform. Mr. Caminetti, Commissioner-General of Immigration, has vitalized the division of information so that it is genuinely aiding the immigrant in making the choice of a home, and is doing splendid work in connection with the employment problem.

Also, by an arrangement with Mr. Claxton, Commissioner of Education, the names of all immigrant children of school age are sent immediately from the various ports of arrival to the school authorities at the point of destination.

Several cities, notably Cleveland, have established immigration bureaus that guard the immigrant from the time of his arrival, watching his education, protecting his rights, promoting his interests, and helping him advance to naturalization.

Of the States, California has moved to the front with a statute providing teachers to work in the homes of immigrants, instructing children and adults in education laws, labor laws, sanitation, and the fundamental principles of American citizenship.

The North American Civic League for Immigrants is a powerful volunteer body that attempts the promotion of applicable legislation, the actual work required to protect the immigrant, and the teaching of the English language.

Through the medium of the Baron de Hirsch Trust, the Jewish immigrant receives far more extensive consideration than that accorded to any other nationality.

The trust maintains distributing agencies at all points of entry, and not only is the alien placed in the business or job for which he has been trained but in the event of his poverty, he is loaned the money necessary for transportation and equipment.

These activities are praiseworthy indeed, but they do not by any means contain the solution of the immigrant problem. The work that is to be done cannot wait upon private generosity or individual initiative, nor will the real answer ever be given by cities or States acting by themselves.

The task of assimilation is national. It is the Federal Government that lets in these millions from other shores, and it is the Federal Government that must accept the responsibility for their protection, development, and Americanization.

The Potential For Policy Success

The one policy that carries with it any certainty of success is a policy that will regard every alien as a ward of the nation, to be guarded, aided, and protected from the very day of arrival to the day of naturalization.

Until they have mastered the language, become acquainted with their rights as well as their duties, and gained a sense of belonging, these strangers within our gates are as children and must be so treated.

Such a policy, taking account of the muddles and maladjustments of the past, will invent machinery of distribution that will end the disastrous stupidity of farmers huddled in industrial centers, tradesmen and professional men herded in mills and factories, and skilled labor wasting itself in unskilled drudgeries—a machinery that will place every immigrant to his own advantage as well as to the benefit of the state.

In the growth of the unemployment problem, and the increase in involuntary poverty may be seen the evil results of the theory that has insisted upon Government as a sovereign power rather than as a working partnership with the people.

In the formulation of sane immigration policy, there is the chance for the Government of the United States to put off its purple robes of aloofness and put on the overalls of empire-building.

Farming, Underrated by Immigrants

Government lands and state lands lie idle while the business of pioneering is turned over to promoters who are concerned only with their profits, caring nothing for the human element that figures in their close bargains.

Where is there a more considerable promise of happiness and prosperity than in the transportation of immigrant agriculturists, in community groups, to this public land, together with such equipment as will enable them to make a flying start in their conquest of the soil? It is not a new idea, or radical, for other countries are using a twenty year-loan system to put people upon the land.

In those isolated cases where immigrant groups have succeeded in getting into agriculture, the result has been industry, thrift, sobriety, education, and Americanization. Italians are growing cotton on the Mississippi Delta, fruit in the Ozarks and Louisiana, and raising garden-truck in the Atlantic Coast States and New England, either rendering worthless land productive by their toil or else developing supposedly waste tracts.

The Poles are lovers of the land, ninety percent of them that come to the United States being eager to engage in agriculture, and the small number able to achieve their ambition have only stories of success to tell.

The Polish farmers of Wisconsin, Illinois, Texas, and Kansas are not behind the native-born in their contributions to the general good, and the Bohemians are others who have done well wherever their feet have touched the soil.

Making the Melting Pot Work

The investigations of the Immigration Commission proved that all of those thus brought into contact with opportunity were grasping it, taking out naturalization-papers, Americanizing in every way, and playing their proper part in municipal, state, and national affairs.

A second necessary step is the creation of a federal system of public employment-bureaus which may minister to the needs of the native-born as well as of the alien.

The individual States have failed abjectly in this respect, for even the nineteen commonwealths that have created free employment-bureaus have done little more than to pile up records of inadequacy.

Federal control would cover the whole country, supplementing and assisting the work of existing organizations, regulating private agencies, and bringing together definitely the jobless man and the man less job.

Here again, it is a matter of imitation rather than innovation, for Great Britain and Germany have for years been operating national labor-exchanges successfully.

The United States must follow the example of European countries, which meet the difficulties of poverty by the advancement of transportation costs and also guard against class control of the machinery by providing that both workers and employers shall have representation on a governing committee.

Solutions for an Overburdened Judicial System

Justice must be made swift and inexpensive, and this cannot be done until the innumerable, and straightforward disputes of the industrial world are removed from the rigorous processes of traditional jurisprudence.

As long ago as 1806, France created industrial courts, and the example has been followed by Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Belgium.

A president, who represents the public, and an equal number of workers and employers sit as a jury rather than as a court. Lawyers are barred; the parties to the dispute take turns relating grievance and defense, and in consequence of this simplicity, ninety percent of the cases are adjusted without formal hearings.

In the event of threatened strikes or lockouts, the courts have the power to sit as boards of arbitration, and it is only in rare cases that satisfactory agreements are not reached.

Compare the simplicity of this procedure with the American method of numerous trials, many appeals, reversed decisions, remanded cases, court costs, lawyers' fees, and months of delay, a gantlet that no poor man dares to run.

The dollar out of which an alien is cheated may mean the difference between a bed or a park bench, and indeed his sense of injustice will not inspire him with respect for democratic institutions.

The Education of Our Future Citizens

The processes of education must be quickened, and greater emphasis should be put upon the preparation of human beings for the business of life. Immigrant adults, as well as immigrant youth, should have the privilege of instruction in the English language, national, state, and municipal government, industrial laws, customs, and ways of American life, hygiene, sanitation, and all other allied subjects that will fit them to be intelligent, useful American citizens.

Germany, through a compulsory system of continuation schools, has control over a youth until his eighteenth year; and although the system has been in force since 1891, it is only now that the United States is taking timid, tentative steps in the same direction.

National standards of education must be raised, and the established principle of federal aid to the poorer States should be carried through to the point where illiteracy will vanish, whether the illiterate be a native-born child or an adult alien. Not the least vital task of the public-school system is to serve the immigrant during his struggle for prosperity and citizenship.

Health and Medical Assistance for Immigrants

Health is no less important than education, and an official investigation has shown that adult delinquency and dependency are primarily due to neglect in connection with the physical defects and deficiencies of the growing youth.

Not alone is it necessary to have medical inspection and dental clinics for every child that passes through the public schools of the United States, but particularly in the case of the immigrant and the poverty-stricken native-born there is need for infant dispensaries, model kitchens, milk stations, visiting nurses, and a program of preventive medicine.

While new machinery in no small measure may be necessary for the doing of all these things, the plant for its housing is already at hand. The school buildings of the United States offer themselves for the purpose in full perfection of convenience, economy, and effectiveness.

As it is today, the schools, which represent the most significant single investment of the people's money, are in use a scant seven hours a day for an average of one hundred and forty-four days a year.

The Integration of the Immigrants

The neighborhood is the group unit next in importance to the family itself, and the school building is the center of the community. What reaches every child in the United States can contact every parent, and not only does the broader use of the school plant hold out its precious promise to the alien, but to the native-born as well.

In every building serving its neighborhood group may be placed the official representative of the federal system of immigrant distribution, the branch office of the federal employment-exchange, the industrial court, the medical inspection-bureau, the dental clinic, the milk station, the visiting nurses, the infant dispensary, the free-legal-aid bureau, the health office, and the juvenile court.

Here is the natural and suitable place for the instruction of the adult alien in English and citizenship, for the art gallery, for the branch library, for the model kitchen, and for the development of the play instinct.

Night use of the school-buildings strikes at the very heart of the leisure-time problem. In cities, thousands of little children play in the streets, menaced alike by the evil environment and the police court, and in the country life is admittedly dull and stagnant. Growing girls are forced into the dance-hall, men into the saloon, and women either gossip across stoops and fire-escapes or become fungous growths in kitchens.

The First Freedom in the New World

In competition with the reckless greed of commercialized amusement, the social center offers amateur theatricals, debates, dancing-parties, moving-picture shows, receptions, gymnasium games, all in a clean, inspiring environment, subjected to the wholesome restraints of the family group and neighborly friendship.

The immigrants can be tapped for their rich store of folk-songs, games, and traditional customs, so that not only will the native-born be enriched and broadened, but the alien given that absolutely essential sense of belonging.

To watch an interracial pageant in a New York school-building, shared in by twenty nationalities, happy, laughing, proud, and friendly is the complete answer to the question of assimilation.

The school building should be the polling-place, and through the medium of the social center, it is possible to effect the self-organization of voters into a deliberative body that will always be in session, the school-house its headquarters.

Would not this be more inspiring to the alien than the location of voting-booths in livery-stables, barber shops, and sheds, or the gathering of voters in some saloon-connected room or in a hall paid for by interested parties out of mysterious funds?

With specific reference to the alien, the school-principal employed by the educational authorities to look after the children of immigrants may also be used by the immigration authorities to care for the adults as well.

His should be the position of neighborhood guardian of these wards of the nation, looking after their inclusion in the proper classes, acquainting them with the services rendered by employment-bureau, health-office, free-legal aid bureau, and visiting nurses, and drawing them into the night play of the social center. In thickly settled communities, where a principal would not have the necessary time, an assistant or assistants might be appointed.

A beginning has been made. Wisconsin, Indiana, Massachusetts, Kansas, New York, Washington, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia are in possession of a law that permits the people to use school-buildings, aside from school hours, for the purpose of meeting and discussing "any and all subjects and questions which in their judgment may appertain to the educational, political, economic, artistic, and moral interest of the citizens." Out of it has grown the new profession of social secretary.

Unity, Purpose and Dynamic Direction

All that is necessary is the adoption of a federal policy that will give unity, purpose, and dynamic direction to what is now isolated and sporadic, and the task of immigrant assimilation is a sound base for such a policy.

Fortunately enough, the money for the work is at hand, and what is more, it is money provided by the immigrant himself. Today, in the United States Treasury, there is a balance of $10,000,000 in the head-tax fund contributed to by every new arrival.

There is no question that this income was primarily intended as a sacred trust fund, for the law of 1882, levying a tax of fifty cents on every immigrant, provided that "the money thus collected . . . shall constitute a fund to be called the immigrant fund, and shall be used . . . to defray the expenses of regulating immigration under this act and for the care of immigrants arriving in the United States, for the relief of such as are in distress, and for the general purposes and expenses of carrying this act into effect."

The Head Tax Equation

In 1894 the head-tax was raised to one dollar, in 1903 to two dollars, and in 1907 to four dollars. In 1909 the immigrant fund was abolished, and the head-tax receipts were dumped into the Treasury, the regulation of immigration being forced to depend upon such annual allowances as Congress saw fit to make.

The $10,000,000 balance belongs to the immigrants, and even if their need were less bitter, it would still be unfair and dishonest to divert a trust fund from its avowed object to purposes that were never intended.

Conclusion

The dreadful European conflict will not have been without its service if the United States, alarmed by the persistence of the hyphen in American life, adopts an immigration policy that in its essence will be a policy of hope, justice, aspiration, and progress for all the oppressed and unhappy, whether they be native-born or strangers within the gates.

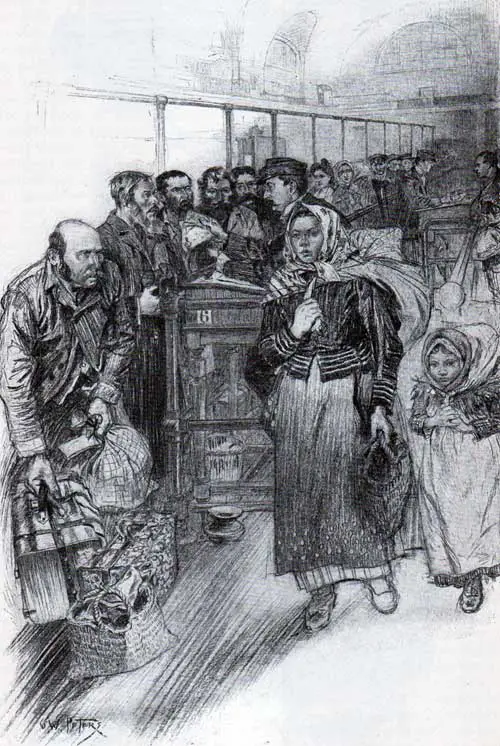

Scenes from Ellis Island by A. Castaigne and G. W. Peters

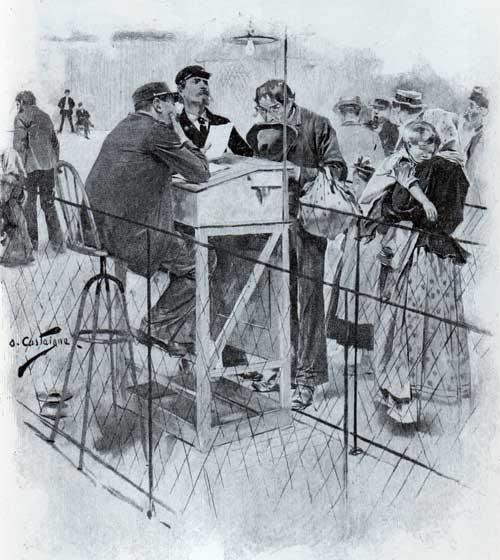

Registry Department at Ellis Island. Drawn by A. Castaigne

This is where immigrants passed through on their way to gaining entrance to the United States. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), where doctors would briefly scan every immigrant for visible physical deformities or diseases. This illustration depicts an immigration inspector reviewing the ship's manifest and record book where information on all immigrants was recorded.

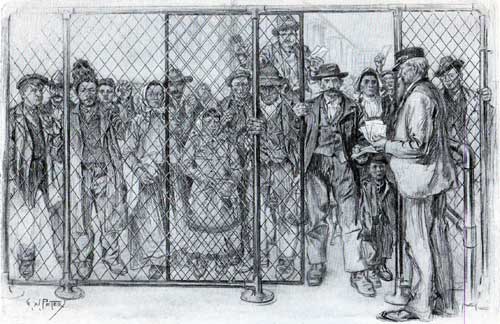

The Registry Desk at Ellis Island. Drawn by G. W. Peters. The immigration inspectors would interrogate each immigrant while seated behind the Registry Desk that held the ships' Manifest (passenger list).

Serving Soup to Immigrants on the Roof Garden at Ellis Island. Drawn by G. W. Peters

The "Deported Pen" Ellis Island. Drawn by A. Castaigne - The deportation pen at Ellis Island contained aliens that were scheduled for deportation back to their country of origin.

Commentary On "The Hopes of the Hyphenated"

IN "The Hopes of the Hyphenated," which appeared in the January number, Mr. Creel undoubtedly points out that which would be ideal both from the point of view of the alien coming to this country and from that of the Government. The article blames the Government, however, for the failure to work out these ideas without allowing that a part of the failure may be due to the age and character of the immigrant.

The point is made that the immigrant is discouraged in his first reception, and delayed and discomfited beyond reason, but the fact must not be lost sight of that it is neither economical nor good management to provide quarters and an inspection force sufficient to handle in a few-hours the widely separated rushes, when these same quarters and men will be idle for months between the chance arrival of several ships at the same time.

It is true that a substantial percentage of the uneducated aliens crowd into colonies of their own race. Those who come here for the first time generally come alone to make enough money to repay their borrowed passage-money to support those left at home, to provide a little capital, and finally to pay for bringing their families to them. That is the primary reason why so much of the alien's money is sent abroad, and why they go to the community where they can exist at the least expense. If our millions go abroad, we receive full value in labor here, and that labor is to a great extent of the sort that our own people are not physically or mentally fitted to do.

For years, while superintending construction-gangs of Italians, Poles. Hungarians, and Bohemians, I was admitted to their friendship and knowledge of their troubles. Among other things, they came to me to send their remittances home, and in few cases was it sent out of this country for other than the reasons given above. I often asked the older men why they came to our work instead of going to the farms, and their answers were always the same. They were too far along in life to learn a new language quickly, and if one must be away from home, why be entirely alone on a farm when one can make more and spend less, and have many friends who speak your tongue and think your thoughts, by living in the colonies or camps? And the work with shovel and a hoe was much the same, whether in a foundation or a field.

Many go back to the old country in the end, but they are the older men who have no families or children with them. It is the nature of all of us to want to spend our old age in the place we remember with the most pleasure, and the alien of more than middle age naturally thinks back to the scene of his younger days as the best place to pass his final years. It is the young and the second generation who will take up citizenship, but those who come to prepare the way for the rest of the family cannot be hurried into this advance either by law or outside effort. If, as Mr. Creel suggests, the Federal Government will adopt a system by which a large number of one race may be given land in the same locality and monetary help, thousands may be benefited, and the land will be in the hands of some of the best intensive farmers on earth.

With the German and English races, it is quite different. Few of them come to us who are of the peasant class or are uneducated. They make good citizens in that they are sober and industrious, but comparatively few of them have become citizens, and such a crisis as the present quickly shows that the welfare of their adopted country is a secondary consideration when compared with the interests of the country of their birth.

If our Government fails to make over aliens into good citizens, the failure is not with the poor and uneducated, but with the well-to-do and well-educated foreigner who comes into our business world, taking all and giving nothing.

Bibliography

Creel, George, "The Hopes of the Hyphenated," in The Century Magazine, Vol. 91, No. 3, January 1916, p. 350-363 with illustrations accompanying this article reprinted from THE CENTURY for February, 1898, and March, 1903, and additional illustrations drawn by A. Castaigne "Deported Pen," 1916.

"Current Comment," in The Century: A Popular Quarterly, Vol. 91, No. p. 637

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.