The Ellis Island Experience: A Detailed Look at Immigrant Inspection Procedures in 1901

📌 Discover the meticulous inspection process at Ellis Island in 1901, where immigrants faced medical exams, legal inquiries, and interviews before entering the U.S. A must-read for teachers, students, genealogists, and historians interested in immigration history and Ellis Island procedures.

Immigrant Being Questioned Through An Interpreter at Ellis Island. The Interpreter (above middle) and a Recorder (far left) Interview Newcomers at Ellis Island. NYPL 79880. | GGA Image ID # 19f4b9efe0

The Ellis Island Immigration Inspection Process in 1901 🗽🚢

This article provides a compelling and detailed examination of the immigrant inspection process at Ellis Island in 1901, highlighting the challenges, scrutiny, and systematic procedures faced by newcomers to the United States. It offers a rich historical perspective on how medical, legal, and economic concerns shaped U.S. immigration policies at the turn of the 20th century.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this article is an invaluable resource, helping to contextualize the rigorous screening process that millions of immigrants endured upon arrival in America.

From medical inspections to legal interviews, from contract labor investigations to deportation proceedings, this exploration of Ellis Island provides a powerful insight into the immigrant experience, highlighting the resilience of those who sought a new life in the U.S.

Procedure Before Reaching Ellis Island

Various witnesses connected with the inspection service in New York describe the methods of inspection at length. When a vessel approaches the harbor, it is boarded by one or two inspectors, who play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the system by examining the cabin passengers. These men, with their expertise and dedication, are confronted with 100 or 150 passengers at a time, and they have an hour and a half for an examination covering the period from touching at quarantine to landing at the dock.

Cabin passengers are asked questions designed to ensure fairness and equity, to ascertain whether they are likely to become a public charge or whether they are under contract to perform labor. If suspicion arises, the individual is brought to Ellis Island for further investigation. No one is allowed to mingle with the steerage passengers until they have passed through the inspection office on the island, ensuring a fair and just process for all.

General Procedures at Ellis Island

After landing at Ellis Island, immigrants pass before the medical officers of the Marine Hospital Service. The rigidity of the medical inspection depends on the general appearance and character of the immigrants. In many shiploads, only a casual inspection is necessary. The greatest difficulty is found in the fact that Italians and Syrians are especially subject to trachoma and favus.

The medical examination of emigrants before embarkation is insufficient. The most effective examination of this kind is at Liverpool, but even there, a physician views them at the rate of 2,000 an hour, even without uncovering their heads. The surgeons in Europe do not recognize two diseases that are grounds for exclusion: trachoma and favus.

After medical inspection, the immigrants file in lines of 30 each, according to the manifests furnished by the steamship company, before the immigration inspectors. These inspectors are registry clerks who speak the immigrants' several languages. Each registry clerk has a steamship manifest before him and examines each applicant to ascertain if there is any discrepancy.

Sometimes, as many as 4,000 persons pass through the office in a day, but the verification is correct, at least as far as the count of the immigrants goes.8 Two or three witnesses complain that the immigration officers are scarcely qualified to perform their duties satisfactorily. An inspector ought to be able to judge each individual according to his merits upon the basis of many considerations.

Poorly Paid Inspectors

The inspectors are poorly paid, and the interpreters are often incompetent to secure correct information. The commissioner of immigration at the port of New York contends that applying the civil-service examination to the position of immigration inspector disadvantages the service.

The system may be satisfactory for clerical positions, but no academic examination based on book learning or linguistic knowledge can guarantee that a person will have the necessary common sense and honesty to decide whether an immigrant is desirable or not. The bureau in New York has had difficulty with men who have been chosen under the civil service rules. The law, moreover, protects men who have never taken an examination.

Immigration inspectors are required to detain for special inquiry all who are not plainly and unquestionably entitled to admission. Under this rule, they detain about 13 to 15 percent of the immigrants. In 1898-99, about 25,000 persons were examined before boards of special inquiry. The proportion of those who require such examination varies greatly in the case of different vessels.

Responsibility of the Steamships

Since steamship companies are required to provide for immigrants during their detention, the amounts paid by the different companies are a fair index of the immigrants' character. These amounts vary from 2 cents per capita for the passengers on board to 50 cents per capita. Only 3 or 4 may be detained on some vessels, while a ship bringing immigrants from Italy may have three-fourths to three-fifths of the passengers detained.

Immigrant Appears Before the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island circa 1907. NYPL 1693106. | GGA Image ID # 19f4d976bc

The board of special inquiry consists of four inspectors specially designated. An affirmative vote of three members is required for admission. Any member dissenting has a right to appeal to the Secretary of the Treasury, and the immigrant has the same right. The decisions of the board, however, are seldom overruled. If the immigrant is excluded, the steamship company bears the expense of deportation.

Contract Laborers

Contract laborers often come as cabin passengers, and it is here that the greatest difficulty in their detection occurs. If the inspector detains the alleged contract laborer, he is then brought before the board of special inquiry for examination, the same as other immigrants who are detained. The authority of the immigration inspectors, on approval by the Secretary of the Treasury, in ordering the deportation of an immigrant whom they deem ineligible is final. The courts recognize this, and they will refuse to review their action.

The law provides for the punishment of an importer who contracts for his employment in this country in addition to the deportation of the contract laborer. There have been but few cases of conviction, although in 6 years, some 4,000 contract laborers were deported.

This is because the law requires that the contract be proven and does not provide punishment for the mere inducement, request, solicitation, or offer of employment. The agreement must also be made in a foreign country to convict the importer.

At present, very few such contracts are made. The more common practice is for the foreman to ask his foreign workers whether they have any friends or relatives they would like to bring to the United States. In this way, large numbers of immigrants reach this country to replace Americans at lower wages.

It is asserted that the wholesale importation of contract labor has practically been stopped. However, the person making the contract is acquitted.

The Criminal Element

Criminals.—The immigration law provides only for the exclusion of persons convicted of a crime, but not for those charged with a crime or those deemed immoral. Although it provides for the exclusion of polygamists, it is impossible to prove such a charge. Consequently, a constant stream of Mormon converts, of whom 90 to 95 percent are women, are continually coming to this country.

Immigration through Canada

The law does not restrict immigration from Canada, and the inspection of those who come from Europe through Canada is wholly inadequate. The United States Commissioner agreed with the Canadian steamship companies, allowing them to board the ships at Canadian ports and pay the United States head tax for those destined for this country. The railroads through Canada agree to transport those not granted a certificate of inspection by these inspectors, entitling them to enter the frontier.

Notwithstanding these agreements, a large number of immigrants from Europe evade the law by giving someplace in Canada as their destination, which relieves them of inspection by the United States officers, and then after remaining there only a short time, they cross over to the American side. This is affirmed to be the greatest loophole in the restriction of legislation. As a remedy, it is proposed that inspectors should be placed along the Canadian border.

Steamship Companies

Before 1893, steamship agents in Europe were very little restricted to persons to whom they sold tickets. The result was an indiscriminate emigration to the United States. The act of 1893, compelling the steamship companies to deport those of their passengers who the inspectors might reject, has made the European agents of the companies the most effective inspectors under the law.

Indeed, the steamship representatives maintain that this inspection class is much superior to that of consular officers or direct representatives of the United States Government.

The reasons given are that the companies hold their agents responsible for immigrants to whom tickets have been sold in case these immigrants are deported. These agents are fully informed of all the details of American legislation and furnished with minute instructions regarding the classes of ineligible immigrants.

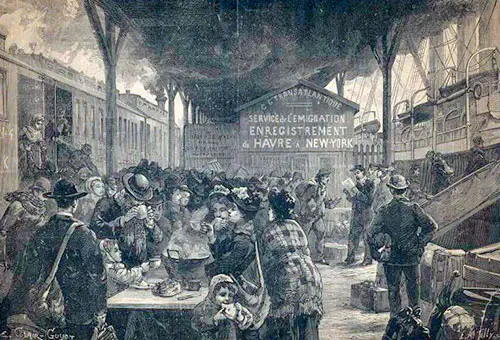

Immigrants at Le Havre, France, 1886. New York Public Library. | GGA Image ID # 21e98598f8

"Section G. Existing Legislation Restricting Immigration." In Industrial Commision on Immigration, Including Testimony, With Review and Digest, and Special Reports, and on Education, Including Testimony, with Review and Digest. Volume XV of the COmmission's Reports, Washington: Government Print Ofice, 1901, Page 16-18.

Who Should Read This & Why?

📚 Teachers & Students

✅ Ideal for U.S. history, immigration studies, and social justice lessons

✅ Explains the immigrant experience through first-hand accounts and historical analysis

✅ Offers insights into early 20th-century public health, labor laws, and government policies

🏡 Genealogists & Family Historians

✅ Helps researchers understand what ancestors went through at Ellis Island

✅ Explains how names, medical conditions, and legal status could impact immigration records

✅ Details procedures that might explain missing or altered family records

⚖️ Historians & Immigration Policy Researchers

✅ Provides a case study of immigration control measures and their effectiveness

✅ Explores early labor laws, public health concerns, and social attitudes toward immigration

✅ Highlights how government oversight and steamship companies shaped immigration policies

Most Fascinating Aspects of This Article

1. The First Line of Inspection: Boarding the Ship & Quarantine ⚓🚢

🔹 As the vessel approached New York Harbor, inspectors boarded to examine first- and second-class passengers, screening for signs of disease or suspicious circumstances.

🔹 Steerage passengers were kept separate from those in first and second class until they passed through Ellis Island’s full inspection process.

🔹 Cabin passengers could be sent to Ellis Island if there were suspicions about their economic status or health condition.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: This dual inspection process highlights class disparities, as wealthier travelers were often allowed to disembark without further scrutiny, while steerage passengers faced intense inspections.

2. The Medical Inspection: Separating the Fit from the Unfit 🏥👀

🔹 Immigrants lined up in groups of 30 for a rapid medical evaluation performed by the U.S. Marine Hospital Service.

🔹 Doctors were trained to spot contagious diseases, disabilities, and signs of mental illness.

🔹 The most common causes for rejection included trachoma (a contagious eye disease), favus (a scalp fungus), and other conditions seen as public health risks.

🔹 Immigrants marked with a chalk symbol (e.g., “K” for hernia, “E” for eye disease, “X” for mental illness) were detained for further examination.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: Ellis Island was the first large-scale health checkpoint in U.S. history, laying the groundwork for modern immigration health screenings.

3. The Legal Interview: Proving Economic & Moral Fitness 📜✍️

🔹 Each immigrant faced an interrogation by registry clerks who verified their information against the ship’s manifest.

🔹 Inspectors checked for discrepancies and attempted to identify contract laborers, criminals, or those considered "morally unfit".

🔹 13-15% of immigrants were detained for further questioning.

🔹 Many inspectors were underpaid and lacked proper training, which sometimes led to arbitrary or biased decisions.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: Even minor errors in documentation or misunderstandings due to language barriers could lead to deportation.

4. The Board of Special Inquiry: A Last Chance for Entry ⚖️🗳️

🔹 Those flagged for additional scrutiny faced a panel of four inspectors who would vote on their fate.

🔹 At least three out of four votes were required to approve an immigrant for entry.

🔹 If denied, the immigrant had the right to appeal to the Secretary of the Treasury, but most decisions were final.

🔹 The cost of deportation fell on the steamship companies, incentivizing them to screen passengers before departure.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: This appeals process was one of the earliest forms of due process in U.S. immigration law, though denied immigrants often had little recourse.

5. Steamship Companies & Their Role in Immigration 🛳️💼

🔹 Before 1893, European steamship agents sold tickets indiscriminately, leading to mass immigration without regulation.

🔹 After new laws were enacted, steamship companies became the first line of immigration enforcement, deporting those denied entry at Ellis Island at their own expense.

🔹 Agents were responsible for ensuring that passengers met U.S. immigration criteria before selling tickets.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: This shows how private corporations played a major role in controlling immigration before federal agencies expanded their authority.

6. Immigration Loopholes: The Canadian Route 🇨🇦➡️🇺🇸

🔹 The lack of strict border control between Canada and the U.S. allowed many immigrants to enter the country illegally.

🔹 Steamship companies paid the U.S. head tax for passengers traveling through Canada.

🔹 Some immigrants falsely claimed a Canadian destination, only to cross into the U.S. days later.

💡 Why It’s Interesting: This demonstrates how immigration laws had unintended loopholes, similar to modern-day concerns over border security.

Key Takeaways for Research & Essay Writing

📌 For Students & Teachers:

🔹 A fantastic primary source for discussions on immigration policy and how Ellis Island reflected broader societal fears about disease, poverty, and crime.

🔹 Highlights how racial, economic, and class biases shaped U.S. immigration laws.

📌 For Genealogists & Family Historians:

🔹 Explains why some ancestors’ names or details might have been changed during the registration process.

🔹 Helps understand why certain individuals were detained or deported.

📌 For Historians & Policy Analysts:

🔹 Provides a case study on the evolution of immigration control and its impact on public health, labor, and national security.

🔹 Shows how the partnership between government agencies and private steamship companies shaped modern immigration policy.

Final Thoughts: The Harsh Reality of Ellis Island Immigration

Ellis Island was a place of both hope and heartbreak. While millions successfully entered the U.S., thousands were rejected due to health concerns, labor restrictions, or bureaucratic errors. This article provides a compelling glimpse into the human side of immigration history, revealing the emotional struggles and resilience of those who sought a new life in America.

🔍 Did your ancestors pass through Ellis Island? Have you ever wondered what they experienced during their inspection?

📖 Explore this fascinating history and uncover the realities of immigrant life at Ellis Island! 🗽🚢