The Deportation of the I. W. W. - 1919

Introduction

The article "Deportation of the IWW," published in 1919, discusses the U.S. government's efforts to suppress and deport members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a labor organization known for its radical views and activism. The article examines the legal actions taken against the IWW during the post-World War I Red Scare, highlighting the intersection of labor rights, political ideology, and immigration policies.

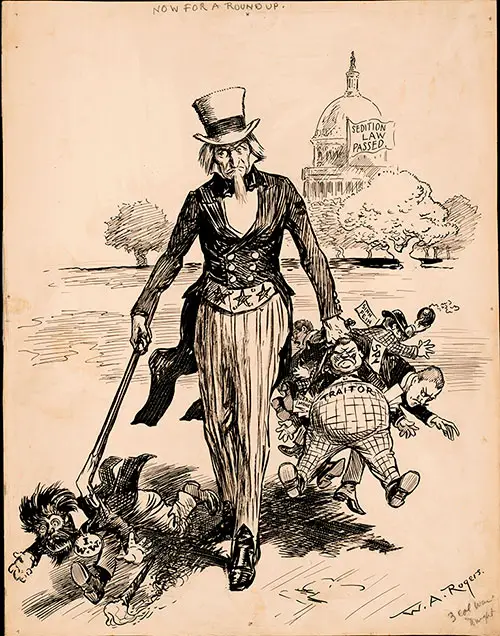

Political Cartoon, "Now for a Round-up" by William Allen Rogers, Artist, 1918. The drawing shows Uncle Sam rounding up men labeled "Spy," "Traitor," "IWW," "Germ[an] money," and "Sinn Fein" with the United States Capitol in the background displaying a flag that states "Sedition law passed" referring to the Sedition Act of 1918. Library of Congress # 2010717793. | GGA Image ID # 15447f84ef

By Charles Recht, General Counsel of the New York Bureau of Legal Advice.

On 5 November 1916, an incident occurred in the City of Everett, State of Washington, which was known as the "Bloody Sunday" of the "Free Speech Fight." This incident forms the keynote to the treatment of the I. W. W. (Industrial Workers of the World) members and shows the reasons for their deportation.

Six men on the excursion steamer "Verona" were killed by a sheriff and his officers, more were drowned, and dozens were wounded. During the subsequent trial, it was determined that some deputy sheriffs were well-supplied with liquor. As a result, they became infuriated and began shooting wildly.

Jefferson Beard, one of the deputy sheriffs, was shot and killed. The murder of this man (although the I. W. W. charges it, he was killed by one of the other deputy sheriffs) resulted in an indictment against seventy-four members of the union.

The trial before Judge Ronald began on 5 March 1917 and ended on 5 May 1917. It resulted in a complete victory for the workers, as all the I. W. W.'s were acquitted. This incident must be remembered to realize the strength of the prejudice that was created and still prevails in the Northwest.

Strikes were taking place daily—when Congress placed a new and effective weapon in the hands of the employers—a law making the deportation of labor leaders possible.

Patriotism was used to cover up profiteering. The law passed in February 1917 provides that the all-time limit shall be removed. The number of years an alien shall have toiled here shall not count in his favor if he dares to voice his disapproval of our economic and social conditions.

In a country where sixty percent of the commonwealth is owned by five percent of the people, there are likely to be people sharply disagreeing with the system.

While the law provides for the deportation of those who "believe in anarchy" or the "unlawful destruction of property," it fails to define what constitutes "anarchy." This omission is the net to catch strikers and labor "agitators." The law of 6 October 1918 is even more stringent

Industrial unrest grew greater after the "Verona" incident—it became acute in the general strike in Seattle in 1919—and the deportation of some of the men seems to have been an ineffective preventive measure. Industrial unrest still exists in Seattle and elsewhere.

Toward the end of 1917, the Industrial Workers of the World lumber branch called a general convention in the City of Seattle. As some of the delegates arrived, they were seized by the local police, the Seattle Minutemen, and the sheriff and turned over to the Immigration authorities for deportation.

There was no charge against these men except for the Industrial Workers of the World membership. The general sentiment of the Northwest was that the new Immigration Law was passed expressly to enable the authorities to break up that powerful labor organization.

Among the men arrested was one John Berg, an old man who had been in the Everett "Free Speech Fight," and the injuries he had sustained there at the hands of a deputy made him a disabled person for life.

The treatment of the men held by the Immigration Commissioner did not even acquire the semblance of legality, which was prevalent in police hearings in Russia under the Czar. Every method of coercion, misrepresentation, misquotation, and denial of justice was used against the prisoners. There are abundant proofs of this.

For instance, to show the cooperation, to say the least, of the local Immigration authorities with the lumber mills, the following letter taken from the Department records may be quoted:

"No. 35012|380 January 29, 1918.

Commissioner of Immigration,

Seattle, Wash.

Dear Sir:

I have to report that yesterday, Deputy U. S. Marshal Wainwright, while at Mt. Vernon, Wash., learned that a strike had been called in one of the lumber companies by several of the I. W. W. members and some of the said members had been taken into custody by the sheriff of Skagit County. Mr. Wainwright telephoned U. S. Attorney Allen, who called me, requesting that this service start a deportation action against the alien ring leaders of the strike.

At the same time, the sheriff of Mt. Vernon telephoned BEN HAGMARK, who he stated was an alien and an I. W. W. agitator. I requested Deputy Marshal Wainwright bring the man to this city for investigation. Upon the man's arrival, he admitted his connection with the organization and his belief therein. Papers and documents in his possession indicate that he was an organizer of the order.

We, therefore, respectfully recommend that a telegraphic warrant for the arrest of this man be obtained on the ground that he has been found advocating and teaching the unlawful destruction of property after he entered the United States. He was a person likely to become a public charge."

(Signed) Thomas M. Fisher.

TMF/AM Immigrant Inspector."

Sometimes, the arrests were made by some of the so-called "Minutemen." It is not taxing the imagination to surmise that these "Minutemen" generally consist of people vitally interested in and identified with commercial interests.

However, if any proof is needed, the following photograph clearly shows the cooperation of the "Minutemen," the Department of Justice, and the Chamber of Commerce.

The arrested men, kept in detention stations in Seattle for fourteen and fifteen months, were finally herded into a train and brought to Ellis Island, New York. This heavily guarded train arrived in New York on February 10, 1919, its passage through the country being heralded in newspaper headlines as the flight of the "Red Special." All kinds of fictitious stories of the terrible terrorists" and the "dangerous I. W. W." were circulated through the daily press.

When the "Special" unloaded its human cargo, the men were conveyed to Ellis Island. No one was permitted to see the prospective deportees—Miss Caroline A. Lowe, an attorney of Chicago, regularly employed by the I. W. W. organization asked for admission. It was denied.

Woman Attorney for Banished "Reds" at Ellis Island. Caroline Lowe, Attorney for Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), was rushed to New York from Chicago in an Endeavor to Stop the Deportation of Foreign Mal-Contents. Government Officials Refused to Permit Her to Interview Prisoners on Ellis Island, Awaiting Deportation. © Underwood & Underwood 15 February 1919 War Department. National Archives & Records Administration 165-WW-429P-1228. NARA # 45532730. | GGA Image ID # 14e1b533a5

Finally, a writ of habeas corpus was used. It was argued at length before Judge John C. Knox, sitting in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. The testimony elicited at the hearing is instructive.

It developed that a written authorization signed by the IWW men had Mr. Byron H. Uhl, Deputy Commissioner of Immigration at Ellis Island, authorizing one of the counsels to proceed with the case. Despite that, the writ was dismissed for technical reasons, such as the attorneys' inability to show authorization to represent the men.

Incidentally, Miss Lowe's testimony, as the petitioner for the writ, revealed discrimination against the IWW in court decisions.

The testimony concerns a defective search warrant issued by the Department of Justice against the Chicago headquarters of the IWW on September 5, 1917, when all of the leading IWW offices in the land were raided.

The attorneys for the IWW organization moved in court to cancel this warrant and secure the return of the papers seized. Similar proceedings had previously been taken in a somewhat different case, in one of Veeder, the attorney for the Armour-Swift-Cudahy Corporations, the Chicago Packers.

In both cases, the return of the papers was essential to the respective defendants as the legality of the indictments depended on the legality of the seizure of the documents. The difference in results, however, appears in this sworn testimony.

"Re-cross-examination by Mr. Recht (on page 61 of the Record). Question: Just one question: Was the Veeder case, Miss Lowe, a case involving the Chicago Packers not? Answer: Yes.

Q. In that case, the papers were ordered returned 2

A. As I recall, it must have been.

Q. This case was a case of the IWW 2

A. Yes.

Q. And the warrant was even weaker?

A. Yes.

Q. And the papers still need to be returned, in this case, the IWW?

A. Not returned and not returned today.

Q. That is all. Step off."

After the dismissal of the writ, which, nevertheless, was dismissed without prejudice to a new application, and through the attorneys' efforts, permission was given to examine the records on file in Washington.

Although the testimony was incorrectly transcribed, having been taken by prejudiced stenographers, the inspector often acting as his stenographer, besides acting as judge and prosecuting attorney—despite that fact, the testimony disclosed such erroneous conclusions that after a delay of three weeks, fourteen of the IWW men were unconditionally released from the island by the department.

The story of the suffering of each of these men would go beyond the bounds of this article. They had been incarcerated for fourteen months in the detention stations, some of them under conditions that impaired their health.

Nineteen of the thirty-eight sent initially to Ellis Island remain there. Five men, sick and discouraged, submitted to deportation a few days after arriving at the island: although it is five weeks since they sailed, no word has been received from them by any of their friends.

They are as fine a set of men as could be found among the pioneer workers of the Northern forests. Almost half of them came from England, Scotland, and Ireland. They are not newcomers to America. Some have been here for more than thirty years.

Through the attorneys' efforts, one was just released. He is over sixty years old. So far as he knows, he may have been born in the United States. This is the only country he has ever known—he has no knowledge of his parents. The chief reason for his attempted deportation to Scotland seems to be that his name is E. McGregor Ross. He also had been in jail for fourteen months.

Another McDonald, though only a laborer, writes English, which would put many college graduates to shame. When he saw the Statue of Liberty, he was moved to poetry and wrote the following:

“Song of the Deportees."

Far across the foam-flecked ocean

Came the hordes from Europe's shore

To enjoy the freedom tendered

To the ones oppressed so sore

By a gold-crowned king or regent

Or a noble or a knight,

We were with those hordes from Europe

From oppression, we took flight.

With a song of joy for freedom

Some of us first saw this land,

We could feel our serfs' chains slipping

From our minds, our tongues, our hands.

We could see Bartholdi's statue—

How the light shone on the sea,

Lighting up the path of freedom

In this land of liberty.

Now we've helped to fell the forest

And we've dug deep in the mines;

We have built towering buildings.

We have laid the railway lines.

And because we asked to share them—

All the profits of our toil—

We must leave this land of freedom

And to others leave the spoil.

In the shadow of the statue

Bartholdi's hand-designed

We are waiting for the mandate.

That will make us leave behind.

All the friends and kin and loved ones

We have here on this fair shore.

We are waiting to be exiled.

From this land forevermore."

The attorneys are charging these deportees that powerful influences and the desire of the lumber corporations to rid themselves of that element in labor, which affects protection through organizations and unions, were behind these deportations and the enactment of the laws. The authorities stoutly deny this.

While it is challenging to obtain clear connecting evidence that satisfies the requirements of a court of justice, the photograph of a letter sent out to the different lumber corporations in the West is a sufficiently identifying clue to anyone.

Of course, the social aspect of the question is a much larger one. The Immigration Law as it exists today gives the Department of Labor such tremendous power that to prevent abuses, its enforcement would have to be entrusted to angels.

The Immigration Inspectors are not saints. It is true that the Commissioner-General of Immigration at Washington, D.C., Mr. A. Carminati, and the Counsellor, Mr. Parker, are kind-hearted and upright men. However, ours is still a government of laws and not of men.

The extension of the Immigration Bureau's powers is typical of the growth of the Executive Department of the Government, which has progressively been and is now encroaching upon the Judiciary and Legislative Departments.

The powers given to the Labor Department have been bitterly condemned by Edgar Lee Masters, a lawyer-poet who argued the Turner Case in the United States Supreme Court in 1904.

Among the men still held and to be deported is a Native American. He is being expelled because, under the Immigration Law, the Immigrant Inspector has the power to decide the question of birth, that is, whether a man is an alien and from what country he comes.

The Immigrant Inspector has the power to determine whether a man is an anarchist or not. He also has the right to define what, in his opinion, constitutes anarchy. No appeal lies from this so-called finding of fact.

This country's residence length no longer protects a man from deportation. No matter how many years he has been a naturalized citizen, his citizenship by naturalization no longer protects him because such naturalization can be revoked.

The question of alien deportation is connected with the earliest traditions of this Republic. Immediately after Washington's administration, the Federalist Party enacted a similar measure, the Alien and Sedition Law.

This Alien and Sedition Law and its attempted enforcement was the doom of the Federalist Party. The Alien and Sedition Laws were wiped off the statute books by Jefferson, and the Federalist Party was wiped out of existence. Will Fate give us another Thomas Jefferson?

Charles Recht, "The Deportation of the I. W. W.," in Pearson's Magazine, New York: Pearson's Magazine, Inc., Vol. 40, No. 7, May 1919, pp.295 -298.

Conclusion

The deportation of IWW members was a significant event in the broader context of the Red Scare, reflecting the intense fear of radicalism and the lengths to which the U.S. government would go to curb perceived threats to national security. This crackdown on labor activists not only weakened the IWW but also set a precedent for how political dissent, particularly from immigrant communities, would be handled in the future.

Key Points

- 🚫 Government Crackdown: The article details the U.S. government's legal actions against the IWW, targeting its members for deportation under the guise of national security.

- ⚖️ Legal Justifications: Authorities used the Espionage Act and other legal frameworks to justify the deportation of IWW members, branding them as dangerous radicals.

- 🛠️ IWW's Labor Activism: The IWW was known for its militant approach to labor rights, advocating for workers' control and opposing war, which made it a target for the government.

- 🌍 Impact on Immigrants: Many IWW members were immigrants, and their deportation highlighted the vulnerability of immigrant labor activists in the face of government repression.

- 📜 Red Scare Context: The deportations occurred during the Red Scare, a period marked by widespread fear of communism and anarchism in the United States.

- 👥 Public Perception: The IWW was often depicted in the media as a dangerous and subversive organization, influencing public opinion in favor of the deportations.

- 🔍 Surveillance and Raids: The government conducted extensive surveillance and raids on IWW offices, leading to arrests and deportations of key members.

- 📉 Decline of the IWW: The deportation of its leaders and members contributed to the decline of the IWW as a powerful labor organization in the U.S.

- 🗽 Civil Liberties Concerns: The actions taken against the IWW raised concerns about civil liberties and the rights of individuals to political dissent.

- 🕊️ Legacy of Repression: The article suggests that the deportation of the IWW members was part of a broader pattern of political repression that would have lasting effects on American society.

Summary

- Introduction to the Deportation of IWW Members: The article discusses the U.S. government's campaign to deport members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) during the Red Scare, focusing on the legal and political context.

- Legal Actions Against the IWW: Authorities used laws like the Espionage Act to target IWW members, accusing them of being radical threats to national security.

- Impact on Immigrant Workers: Many IWW members were immigrants, making them particularly vulnerable to deportation, which weakened the labor movement.

- IWW's Radical Stance: The IWW's advocacy for militant labor rights and opposition to war placed it in direct conflict with the U.S. government.

- Public and Media Perception: The IWW was portrayed as a dangerous organization, which shaped public opinion in favor of government actions against it.

- Surveillance and Raids: The government intensified its surveillance and raids on IWW offices, leading to the arrest and deportation of key figures.

- Decline of the IWW: The deportation of its leaders contributed to the organization's decline as a significant force in the American labor movement.

- Civil Liberties Issues: The article raises concerns about the impact of these actions on civil liberties and the right to political dissent.

- Broader Context of Repression: The deportations were part of a larger pattern of political repression during the Red Scare, with lasting implications for American society.

- Conclusion and Legacy: The article concludes by reflecting on the long-term effects of the government's crackdown on the IWW and its implications for future labor and political activism.