Pastry Making Simplified - 1923

By Mary D. Warren

The fundamentals of pastry making must be mastered before one can achieve success in pie making. Whether the finished result is to be just a plain, substantial, home everyday sort of pie or a thistle down creation of puff paste, or any one of the many variations between the two, one must understand the rules of the process, quite as the artist must understand the mixing of his pigments.

In fact one must, in a way, have the deft touch of the artist to be able to make really fine pastry, but fortunately this touch may be acquired by practice and experiment and attention to the rules.

There are three classes of pastry: a plain but flaky and tender sort that answers excellently for the usual pie, or as a foundation for a baked fruit pudding or a hearty meat pie or some other dish which must be appetizing, though not too rich or expensive; the second type is slightly richer, rather more delicate, very flaky and liner than the first variety, and is usually reserved for fine pies, for various little entrees and savories, and for making patty shells, tarts and similar dainties when puff paste is not desired.

Puff paste, the third form of pastry, is that very fine, rather spectacular variety of which the handsome vol-au-vent or the genuine patty shell and other rich and sumptuous dishes are made; and when one has learned the method of its manufacture it is no more difficult, though a little more tedious, than the ordinary pie crust to make.

IN MAKING all three types of pastry the same four ingredients are required: flour, shortening, salt, and cold water, though there are modifications of the foundation recipes in this branch of cookery just as there are in every other.

For instance, in the plain pastry a small quantity of baking powder is sometimes added, as I will explain later; in the flaky pastry two varieties of shortening are used; while in the puff paste only butter is permissible.

Flour for pastry may be of the kind which we know as pastry flour, or one may use any good all-round sort, taking care always that the brand is a reliable one; lard for pastry must be always fresh and firm, and of the best quality.

If one of the commercial substitutes is preferred it also should be cold and firm. Butter must be hard or, as the bakers say, tough; water must be icy cold and the pastry should, if possible, be made in a cool place; and if convenient the finished pie or tart or other product, even if made of the plain pastry, should be chilled for fifteen minutes to half an hour before it is baked. This will make the crust flakier and prevent its shrinking from the sides of the pan during the baking.

If a cooked filling is to be used in a two crusted pie, always cool it before it is placed in the pan, for a hot filling will cause the upper crust to shrink and will spoil the appearance of the finished pie.

On the other hand, the filling for a custard or other one-crusted pie should be placed in the pan hot; then the pie will bake more evenly, and the outer part will not be finished before the center.

Grease the pans for plain or flaky pastry—then the crust will be browner on the underside— but wet them with cold water for puff paste. It is well, even when using fine pastry for the upper crust of a pie, to make the lower crust of the plain pastry, for the richer sort will absorb juices and become heavy and indigestible.

A few directions now as to the correct oven temperature for pastries of all varieties will be appropriate, for the baking is very important. All classes of pastry require a hot oven for their baking; what old-fashioned folks would have termed a quick oven, but what we who know the value of the oven thermometer understand to mean from 425 to 450 degrees Fahrenheit.

For plain pastry or pies with two crusts 425 to 450 degrees will be correct. Flaky pastry if used for pies or for the upper crust on a two-crusted pie will require the same temperature, while small articles made from flaky pastry will need 450 degrees to make them perfect.

Puff paste demands an oven temperature of 450 to 500 degrees, according to the size of the article made from it. A hot oven and cold pastry form one of the surest roads to perfection. The temperatures given are intended for use with a reliable oven thermometer which can be placed inside the oven.

Gold Medal Flour - Eventually - Why Not Now © 1916 Washburn-Crosby Co.

Now for our first foundation formula. This is one in which I have included baking powder. It is intended for the beginner in pie making, or for the housewife who has difficulty in achieving good plain pastry:

- 1 ½ Cups of Flour

- ¼ Teaspoon of Baking Powder

- ½ Cup of Lard

- About ¼ Cup of Cold Water

- ½ Teaspoon of Salt

SIFT flour, salt and chop baking powder together, and chop in the cold shortening—which may be either lard or one of the good commercial substitutes—or rub it in with the tips of the fingers; when thoroughly blended make a well in the center of the mixture and pour the water in a little at a lime, tossing some of the flour and lard into it gradually.

It is of great importance that the water should be thoroughly incorporated with the dry ingredients, for unless it is well distributed the pastry will be tough or brittle instead of tender and flaky. Never use any more water than the flour will barely absorb, for too much liquid will be the ruination of any pie.

Next turn the mass out on a scantily floured molding board and, without kneading it or handling it any more than you can possibly help, roll it out with a floured rolling pin, using long, swift, deft motions; when it has become a sheet of a quarter of an inch in thickness it is ready to use.

Be very careful in handling the dough to be light-handed; too vigorous manipulations, too much zealousness in working it, spell failure. Try to regard the ingredients in your pastry as so much gossamer and chiffon, rather than prosaic flour and lard, and handle them accordingly.

Plain pastry may be converted into a delicate flaky variety by rolling out, dotting over with cold crumbly butter, then folding over and rolling lightly until the butter is incorporated into the dough in layers.

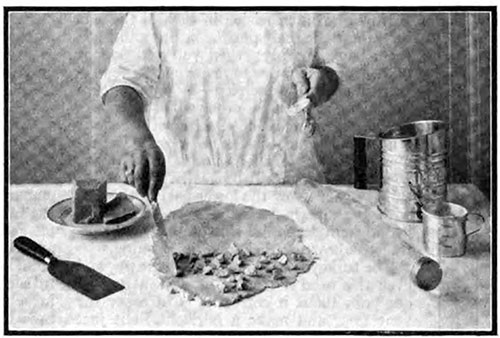

Flaky pastry may be made on the same foundation rule, or one may use a separate and distinct recipe for it. For the first method, roll the plain pastry out in a sheet, as directed, then cut two tablespoonfuls of butler into tiny pieces and scatter them over tile surface of half the sheet and just dust with flour.

Fold the other half of the pastry over this, press the edges together all around, and roll out again the same way; this time sprinkle only a teaspoonful of cold crumbly butter over the paste, with a dusting of flour, and fold again. Roll out and the pastry is ready for use; but if you can conveniently give it a half hour's sojourn in the refrigerator it will be vastly improved.

But if you are desirous of making only some dainty little patisseries for luncheon or afternoon tea and have no wish to prepare the foundation of plain pastry, then you may use this formula for flaky pastry:

- 1 ½ Cups of Flour

- ½ Teaspoon of Salt

- ¼ Cup of Lard

- ¼ Cup of Butter

- About ¼ Cup of Ice Water

PLACE the butter in a bowl of cold water and wash all the salt and buttermilk from it. When it has become waxy and pliable pat it in a little cake, fold in cheesecloth and set away in the refrigerator.

Sift the flour and the salt together and chop in the cold lard or rub it in with the finger tips, then moisten with the very cold water, as in making the plain pastry, and turn out on a floured board.

Roll the pastry out in a sheet and place the butter pat on one half of it, fold the other half over, luck in the edges all round, and roll it out in a sheet; dust with flour and fold in three, then roll it out again, dust with llour and fold, place on a pan in the refrigerator, to become thoroughly cold, then roll out in a sheet and cut as desired.

McDougall's Self Raising Flour © 1907 Mrs. Beeton's Every Day Cookery

Now we arrive at puff paste, the aspiration of every woman who likes to cook, but too often her bite noire as well. Formerly puff pastry was made with eggs, but modern methods require only flour, salt, butter, and ice water.

To expert makers of puff paste it may seem a sacrilege to suggest a quick, short method for its making, but the modern housewife must needs learn short cuts, and I am quite sure she will welcome this modern method which has done away with much of the labor and mystery of puff-pastry manufacture, so that by this simple and easy process this type of pastry becomes as light and in complex a matter as the making of the most homely or frugal pie.

There are, however, a few preliminaries that must not be overlooked if one would succeed in producing really fine puff paste.

First, the ingredients for the pastry must be cold, the room in which it is made should be at least cool, and the utensils themselves also should be chilled for a while in the refrigerator before the work is begun.

These preparatory steps having been taken, one may proceed to the formula for the pastry:

- 2 Cups of Sifted Flour

- ½ Teaspoonful of Salt

- 1 Cup of Butter

- About ¼ Cup of Cold Water

A CHOPPING bowl is one of the best utensils for making puff paste. It should of course be very clean and very cold. Sift the flour and salt into it, then cut the chilled butter into pieces and drop them into the flour.

Now with the cold chopping knife cut the butter into the flour until it is well incorporated with it but still remains in distinct pieces about the size of peas.

Then make a little well in the center of the flour-and-butter mixture and pour in a part of the cold water; toss the dry ingredients into the water and see that the latter is well distributed.

Add more as necessary, and finally turn the cold pastry, which up to this moment has not been handled at all, out on a cold molding board— an old marble slab which has been well scoured is ideal for this work —and without kneading or working it in the least press it into a square; then roll it out, letting the bits of butter fall as they will, into a sheet longer than wide.

Fold this in three, gathering in any stray crumbs, and turn it halfway round, then roll again, and turn the pastry about.

Do this in all four times, placing the pastry in the refrigerator between each time rolling if it seems to be growing warm, then fold it once more and place it on a pan, cover with a piece of cheesecloth and chill it for an hour, or longer if convenient.

When you are ready to bake your pie or other desserts be very sure that your oven is hot before you take the pastry from the refrigerator. Puff pastry must be baked in an oven heated to at least 450 degrees Fahrenheit.

Five hundred degrees will be better if the heat of the oven can be controlled quickly and one has no other duties to prevent her from watching the baking rather closely.

Very cold pastry and a very hot oven are the only secrets to successful puff-pastry making; the baking must be practically finished before the butter has an opportunity to melt. Then, and then only, will the puffing be entirely satisfactory.

Fruit pies may be made from the plain pastry or from a combination of the plain and flaky pastry. In the latter variety the pans will be lined with the plain and the pies topped with the flaky pastry. Such a pie is usually very fine if the baking has been carefully managed.

From the flaky pastry one may make very fine out-of-the-ordinary pies, or the same pastry may be used in preparing any of the delicate little patisseries usually made from the puff paste.

Tarts, turnovers, rissoles, cheese puffs and patties are all very satisfactory when made from it. Whichever pastry may be selected the method for its use should be the same, and one must always observe the rule of very little handling, cold pastry and a hot oven.

Patty cases made from puff paste may be a single thickness of the dough with the center cut nearly but not quite through, or they may be built up with rims, the centers oj which are baked separately and used as covers if wished.

Delicious pastry cases may be made from flaky pastry, rolled quite thin, cut in rounds, and fitted snugly over inverted muffin or patty pans. Prick well to prevent blistering and bake in a hot oven until a delicate brown.

PATTY cases are cut from the pastry rolled about a quarter of an inch thick. They may be of any desired size. Cut the rounds for the foundations, and if puff paste is used place them on pans which have been slightly dampened with cold water.

Then with a small cutter press the center of the pastry almost through, set the pan aside to chill the patty cases for half an hour, then brush gently with the yolk of an egg beaten with two or three tablespoonfuls of milk or water.

As the pastry will not rise to its full height where the egg yolk touches it, care must be taken not to permit the glaze to spread over the sides of the patty cases. Place the pan containing the pastry on the lower shelf of the oven and bake in a temperature of 500 degrees Fahrenheit to a russet brown.

When the cases are taken from the pan lift the little center lid and scoop out the soft inside portion with a small spoon; then the patty cases are ready to be filled with creamed chicken and mushrooms, with oysters, sweet breads, tuna fish or with some delectable sweet creamy mixture to be served as a dessert.

Patty cases may be built with rims if preferred, and if the flaky pastry is used this is always advisable.

Mary D. Warren, “Pastry Making Simplified,” in The Ladies’ Home Journal, November 1923, p. 161, 169