Guion Line and Inman Line

1882 Ocean Steamships Article by S. G. W. Benjamin - Part 3

Fineness of lines is equally essential, together with the proper distribution of weights, and the like. The great average speed exhibited by the modern steamship is due in large part to the momentum of such a vast weight, which, once started, has a tremendous force in overcoming resistance.

Thirty years ago sixteen days was a fair allowance for the passage between England and New York by steam. By gradual steps the point was reached when eleven days was the minimum, and this startled the world. Then began a rivalry between the Inman and White Star lines, attended by a succession of runs showing a gradual increase of speed, which proved a great advertisement for these lines.

In 1871 the average time of twenty-four crack voyages by these lines was eight days, fifteen hours and three minutes. The Adriatic's best westward time was forty-three minutes less. It should be remembered that the westward passage is generally longer than in the other direction, owing to westerly winds and the Gulf Stream.

In emulation of this speed in 1877 the City of Berlin, of the Inman line, made the trip to Queenstown from New York in seven days, fourteen hours and twelve minutes, and in the same year the Britannic, of the White Star line, crossed from Queenstown in seven days, ten hours and fifty-three minutes.

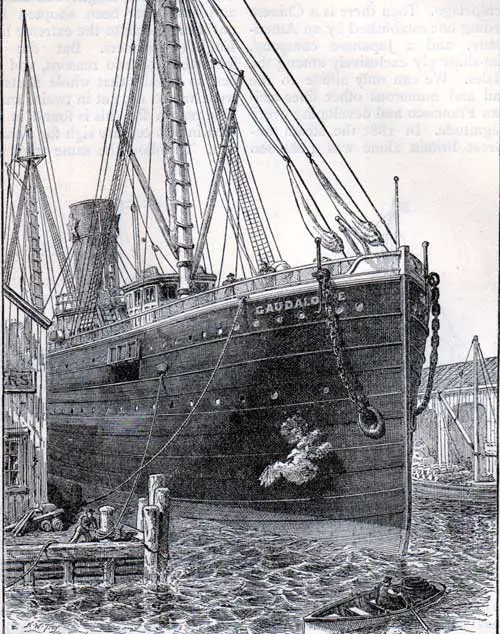

Illustration of the Bow of an American Steamer The Gaudalope

In 1879 a new rival appeared in this field, the Arizona, of the Guion line. This steamship made the eastward passage in 1880 in seven days, ten hours and forty-seven minutes, and in one trip in 1881 she lessened this time about three hours. This seemed to be about the best that could be expected of these superb ships, when the new Guion steamer, Alaska, after a number of astonishing runs, accomplished the westward passage between the two ports, on April 18, 1882, in seven days, six hours, and twenty minutes, actual time, against heavy seas.

In a subsequent trip eastward she ran the distance in six days and twenty-two hours, actual time. In this, the quickest passage ever made across the Atlantic, the Alaska traveled 2895 knots, being about an average of 4I84 knots per day, for seven successive days. (See table of Quickest Trips Below)

It will be observed that the increase of speed has been graduated in proportion to the gradual increase of size. The ships of 185o were rarely much over 2500 tons, and were barely 300 feet long. Now the average length of ocean steamers is upward of 400 feet, while 500 feet is not uncommon.

Two Ways of Crossing the Ocean

The City of Rome is 586 feet long, and registers 8826 tons; the Servia is 530 feet, and 8500 tons; the Alaska is 52o feet, and 6932 tons. The Austral, intended for the Australian trade, is 474 feet long and 48 feet 3 inches broad, and registers 9500 tons. The measurements of this vessel, and of the new Cunarder Cephalonia, which is 44o feet long by 46 feet beam, indicate that the reaction against extreme length has already commenced in the great ship-yards of Great Britain, being in each of these cases less than ten beams to the length.

Another feature of the modern steamer is the system of compartments, which may serve to stiffen the vessel and should insure safety from injury by collision, but has not proved a certain element of safety.

The bluff bow or straight stem is another peculiarity of the contemporary screw steamer. It was originated by the Americans, the great length of the modern ship obviating the necessity of a bowsprit for head-sail, and the cut-water being therefore a useless expense.

The Inman line alone among prominent lines retains the cut-water and figurehead, as shown in the accompanying cut of the City of Rome. But it is already questioned in some quarters whether it would not be well to restore some form of cut-water, or projection, as a means of reducing the great danger now resulting from collision with the sharp edged bow. Nothing can be claimed for the straight stem on the score of beauty; but utility and economy are of prime importance in commercial naval architecture.

Quickest Trips of Ocean Steamships On Record (1882)

| Steamer | Sailed From | Time | Date | Arrived At | Time | Date | D | H | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | Sandy Hook | 17:42 | 30 May 1882 | Queenstown | 20:04 | 6 Jun 1882 | 6 | 22 | 00 |

| Arizona | Sandy Hook | 10:10 | 27 Sep 1881 | Queenstown | 22:20 | 4 Oct 1882 | 7 | 7 | 48 |

| Servia | Sandy Hook | 17:25 | 18 Jan 1882 | Queenstown | 05:53 | 26 Jan 1882 | 7 | 8 | 06 |

| Britannic | Queenstown | 16:35 | 10 Aug 1877 | Sandy Hook | 23:06 | 17 Aug 1877 | 7 | 10 | 53 |

| Germanic | Queenstown | 10:25 | 6 Apr 1877 | Sandy Hook | 17:40 | 13 Apr 1877 | 7 | 11 | 37 |

| City of Berlin | Queenstown | 19:00 | 5 Oct 1877 | Sandy Hook | 04:50 | 13 Oct 1877 | 7 | 14 | 12 |

| City of Rome | Sandy Hook | 10:29 | 22 Apr 1882 | Queenstown | 06:15 | 30 Apr 1882 | 7 | 15 | 24 |

| Gallia | Sandy Hook | 11:28 | 4 May 1881 | Queenstown | 10:40 | 12 May 1881 | 7 | 18 | 50 |

From Sandy Hook to Queenstown deduct 4 hours 22 minutes for difference in time.

Queenstown to Sandy Hook add 4 hours 22 minutes for difference in time.

That the employment of masts and rigging is not greatly detrimental to the average speed of a fast steamer is shown by the fact that the fastest trips have been made by steamers carrying the heaviest spars. The steamer of the present day is provided with jury masts, rather than the heavy spars she would carry if she were a sailing ship.