Evolution of the Ocean Steamship

1882 Ocean Steamships Article by S. G. W. Benjamin - Part 1

The employment of steam as motive power is by no means a modern idea. The possibilities of steam were known to the ancients; its applications were described by Hero, 13o B. C. Roger Bacon, in the fourteenth century, made some experiments, and Blasco de Garay constructed a rude steam-boat at Barcelona in 1543. Later, Papin built a steam-boat in Germany, which was of sufficient importance to arouse the superstitious dread or conservative opposition of the bargemen, who destroyed it.

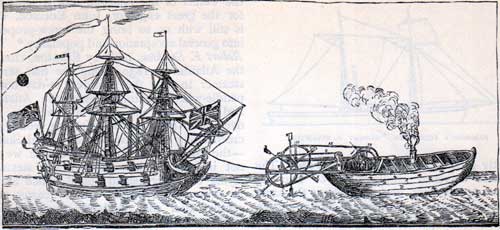

Many others gave their attention to the subject, but Jonathan Hulls of Liverpool appears to have been the first to reduce the marine steam-engine to actual practice. In 1737 he published a pamphlet describing his stern-wheel boat, accompanying it with an engraving, which is yet in existence, and from which it would appear that it was capable of towing a large vessel.

It is a little curious that the first form which the invention followed was that of the stern-wheel. Those who think that the first thought is the best may find confirmation of that opinion by observing that not only is the stern-wheel widely used on the rivers of the west to-day, but stern propulsion under a modified form is, after many experiments, and a long trial of lateral propulsion, the plan upon which the world has finally settled for marine navigation.

The principle of the screw propeller suggested itself early in the history of steam. At first it was attempted with a sort of Archime dean screw; but the bladed propeller was soon found to have greater efficiency. Of course, as in all great inventions, there are many claimants for the priority of invention. But although the great discoveries have generally been made simultaneously by active minds resident far apart and even ignorant of each other's existence, the fame of the invention is generally accorded to the man who first reduces the new invention to practice.

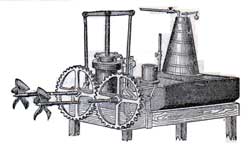

Fulton has the credit of inventing steam navigation, but his boat, the Clermont, was a paddle-boat, the idea of which he borrowed from Symington's steamer, Charlotte Dundas; while two years earlier that great inventive genius, John Stevens, of Hoboken, N. J., had built a steamboat propelled by a screw, the model of which may now be seen in the Museum of the Stevens Institute of Technology at Hoboken. Men are now living who have seen Stevens's and Fulton's boats and the Servia, the great Cunarder, on the waters of the river up which Hudson steered the Half Moon not three centuries ago.

The Savannah was the first steamer which crossed the Atlantic. (Note 1) She was originally intended for a sailing ship of three hundred and fifty tons, but was purchased on the stocks by Mr. Scarborough, who deserves credit as the first to send a steamship across the most stormy of seas.

HULLS'S STEAMER

Moses Rogers was engineer and Captain Stephen Rogers was master. On the 26th of May, 1819, the Savannah sailed from Savannah on her memorable voyage. She arrived without mishap at Liverpool in twenty-two days. In 1825 the steamer Enterprise went from England to Calcutta. But the acceptance by the world of steam navigation was not so rapid at the outset as one might think, for the rate of speed attained was often surpassed by the splendid runs of the packet ships.

Propeller Built by John Stevens in 1804

It is said of Captain Cobb, who made many fine trips in a sailing packet, that on leaving Liverpool for New York he gave a letter for his wife to the captain of a steamer that sailed on the same day for New York. After bowling across the Atlantic to Sandy Hook at a fine rate, he learned from the pilot that the steamer was not yet in sight. Laying his ship alongside the dock without delay, Captain Cobb went to his house and awaited the arrival of the steamer.

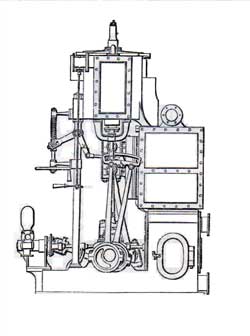

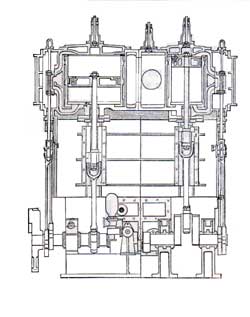

Machinery of First Propeller Built by Stevens

When she, too, had anchored, her captain hastened ashore to deliver to Mrs. Cobb the letter from her husband, and much to his chagrin was met at the door by Captain Cobb himself. The inefficiency of side-wheels, together with the enormous cost of the fuel required for a trip, was the second cause operating against the employment of steam. The fine old steamship Lafayette, for example, registered three thousand tons; her machinery weighed nearly one thousand one hundred tons and she required upward of one thousand tons of coal. Judge what was the space left for remunerative cargo.

Two great modifications in the steam navigation of the seas have within a comparatively short period covered the seas with an intricate and almost ubiquitous net-work of steamship lines. We refer to the adoption of the screw-propeller and the compound engine. The former gives greater speed with a given power, and the latter vastly greater power with far less fuel.

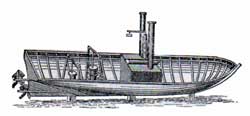

Propeller "Phoenix," Built by Stevens in 1806

The almost universal employment of iron for ocean steamships, beginning about the same time with the improvements in motive power, must also be considered as by no means an unimportant element in bringing forward the enormous speed of steam navigation on the seas, if for no other reason than that the larger stowing capacity of iron ships over wooden ones places a larger surplus of tonnage in the market in proportion to the steam power employed.

We have used the word " adoption " advisedly, for the invention of both the screw and the compound engine was either nearly simultaneous with or antedated the paddlewheel and ordinary beam engine. The idea of the screw for propelling was suggested ages ago. Stevens's steamer Phoenix made a sea-voyage with a screw from New York to Philadelphia in 1808, seeking the waters of the Delaware because Fulton and Livingston had the patent right to steam navigation on the waters of the Hudson. But it remained for the great engineer, John Ericsson, who is still with us, to bring the screw-propeller into general acceptation and popularity. (Note 2)

Ericsson's Propeller Steamer "Robert F. Stockton"

The Robert F. Stockton, built by Ericsson, crossed the Atlantic in 1839, being the first screw-steamer to take the venture; today not a paddle-wheel steamer crosses the Atlantic, and but a few old craft of that sort, too decrepit to break up for kindling wood, still creep along the coast of the United States, -- the last of their kind.

Of course we do not include in this category the steamers plying on Long Island Sound, which are in no sense ocean boats. For a quarter of a century after the Stockton arrived in New York paddle-wheels were the fashion.

The previous year (1838) the Sirius and the Great Western arrived in New York on the same day, the former from Cork, and the latter from Bristol in fifteen days, and at the very time when distinguished scientists were trying to demonstrate that it was impossible to carry a sufficient amount of coal to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Compound Marine Engine

|

|

|---|---|

| Front elevation | Side elevation |

The Great Britain, with four masts, came to New York in 1846, and excited as much astonishment as the Great Eastern did fifteen years after. The writer well remembers being taken on board by his father, and as he pushed through the dense throng of visitors, he gained an impression of size such as surpasses that produced by a sight of the much larger leviathans of to-day.