The Great Western - Steamer from 1837

Photographs Show the Great Eastern Docked at Harbor in New York City, New York. Also, a "Western Hotel" Coach and People on the Dock. Stereograph c1860. GGA Image ID # 13eca3c25e

The Great Western was launched on July 19, 1837, and was towed from Bristol to the Thames to receive her, machinery, where she was the wonder of London. She left for Bristol on March 31, 1838; and arrived, after having had a serious fire on board, on April 2d.

In the meantime others had been struck with the possibility of steaming to New York; and a company, of which the moving spirit was Mr. J. Laird, of Birkenhead, purchased the Sirius, of 700 tons, employed between London and Cork, and prepared her for a voyage to New York.

The completion of the Great Western was consequently hastened; and she left Bristol on Sunday, April 8, 1838, at 10 A.M., with 7 passengers on board, and reached New York on Monday, the 23d, the afternoon of the same day with the Sirius, which had left Cork Harbor (where she had touched en route from London) four days before the Great Western had left Bristol. The latter still had nearly 200 tons of coal, of the total of 800, on board on arrival; the Sirius had consumed her whole supply, and was barely able to make harbor.

Model of the Persia and Scotia

It is needless to speak of the reception of these two ships at New York. It was an event which stirred the whole country, and with reason; it had practically, at one stroke, reduced the breadth of the Atlantic by half, and brought the Old and New World by so much the nearer together.

The Great Western started on her return voyage, May 7th, with 66 passengers. This was made in 14 days, though one was lost by a stoppage at sea. Her average daily run out was 202 miles, or about 8 1/2 knots per hour; in returning she made an average of close upon 9.

Her coal consumption to New York was 655 tons, though in returning it was but 392 tons—due no doubt to the aid from the westerly winds which generally prevail in the North Atlantic in the higher latitudes. She made in all, between 1838 and 1843, 64 voyages across the Atlantic, her average time from Bristol or Liverpool to New York, with an average distance of 3,062 1/2 knots, being 15 days 12 hours, and from New York eastward, over an average distance of 3,105 knots, 13 days 6 hours.

Her fastest westward passage was in 12 days 18 hours; her longest, in 22 days 6 hours. Her fastest eastward was in 12 days 7 1/2 hours; and longest, in 15 days. The largest number of passengers carried was 152, and she averaged throughout 85.

In 1847 she was sold to the West India Steam Packet Company, and in 1857, about the time that Mr. Brunel was launching his last and greatest ship, she was broken up at Vauxhall; and her final province no doubt was to feed the drawing-room fires of the West End of London, a fate to which many a worn-out wayfarer of the seas is yearly devoted.

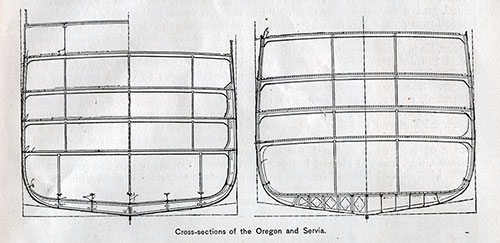

Cross-sections of the Oregon and Servia.

The founding of Cunard Steam Ship Company

Steam communication between England and America had thus been demonstrated as possible beyond a doubt, and others were not slow to make the venture. The Great Western Company themselves determined to lay down a second ship; and it having been quickly seen that the mails must be henceforth carried by steam, a gentleman from Halifax, Nova Scotia, appeared upon the scene, who was destined to connect his name indelibly with the history of steam upon the Atlantic.

This was Mr. Samuel Cunard, who had nursed the idea of such a steam line for some years, and who now, with Mr. George Burns, of Glasgow, and Mr. David McIver, of Liverpool, founded the great company known by Mr. Cunard's name.

The establishment of this line and the building of the Great Britain (page 519) by the Great Western Company are two most notable events in steam navigation—the one putting the steam traffic between the two countries on a firm and secure basis; the other marking a notable step in the revolution in construction and means of applying the propelling power, destined before many years to be completely accepted to the exclusion of the wooden hull and the paddle-wheel. It is not fair to speak of the use of iron in the Great Britain for the hull, in a general way, as the beginning of the change; she was only the first large ship to be built of this material.

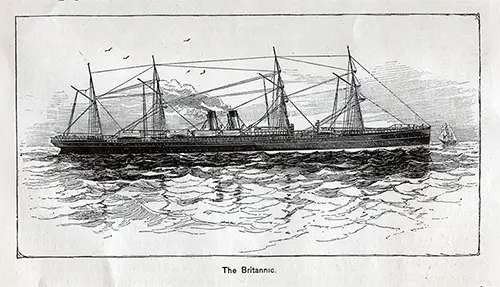

The Britannic

The credit of the introduction of iron is largely to be awarded to Mr. John Laird, of Birkenhead, who in 1829 built a lighter 60 feet long, 13 feet 4 inches in breadth, and 6 feet depth of hold; and in 1833, a paddle-wheel steamer, the Lady Lansdowne, of 148 tons, 133 feet long, 17 feet broad, and 9 feet 6 inches deep. "

In the following year Mr. Laird constructed a second paddle-steamer, for G. B. Lamar, Esq., of Savannah, United States, called the John Randolph. This was the first iron vessel ever seen in American waters. She was shipped in pieces at Liverpool, and riveted together in the Savannah River, where for several years afterward she was used as a tug-boat."

Though Mr. Laird was the ablest upholder of iron as a material for shipbuilding, and was the largest builder in it, the idea existed before him—Richard Trevithick and Robert Stevenson so early as 1809 proposing iron vessels, " and even suggested 'masts, yards, and spars to be constructed in plates, with telescope-joints or screwed together;' and in 1815 Mr. Dickenson patented an invention for vessels, or rather boats, to be built of iron, with a hollow water-tight gunwale " (Lindsay, vol. iv., p. 85).

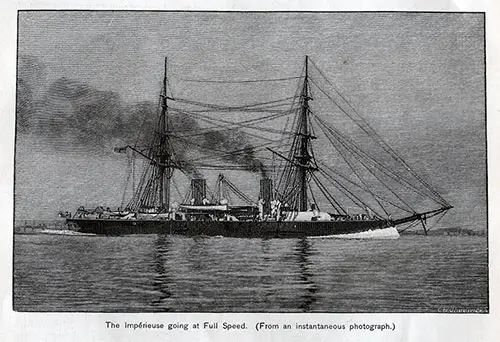

The Impérieuse, going at Full Speed. (From an instantaneous photograph.)

But nothing came of these proposals, and the first iron vessel mentioned was built in 1818 by Thomas Wilson, near Glasgow—the first steam vessel being the Aaron Manby, " constructed in 1821 at Horsley " (Lindsay). "

Up to 1834, Mr. Laird had constructed six iron vessels altogether;" the largest of these was the Garryowen, of 300 tons, for the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. Others of considerable size by the same builder followed, and the material began to come into use elsewhere. In 1837 the Rainbow, of 600 tons, by far the largest iron steamer which had yet been built, was laid down at Birkenhead.

It will thus be seen how bold was the step taken by Mr. Brunel when, in 1838, he advised the Great Western Company to use iron as the material for their new ship, which was to be of the startling size. of 3,443 tons displacement. Nor were his innovations to stop with size and material. On his earnest recommendation to the company it was decided, in 1839, to change from the first design of the usual paddlewheels to a screw.