Hidden Passengers: The Dangers, Tricks, and Fates of Stowaways (1906)

From death-defying escapes to tragic misfortunes, stowaways in the early 1900s risked their lives to cross the seas illegally. Some hid in lifeboats, freight crates, and engine rooms, while others faced death, deportation, or imprisonment. Discover the astonishing true stories of transatlantic stowaways and the maritime laws that tried to stop them.

An interesting read about a few of the more intriguing stowaways from the early 1900s. You'll chuckle about the exploits of some, be amazed at the exploits of others, and learn about the unfortunate stowaways who made poor choices.

The annual number of stowaways that come to port on the transatlantic liners is far greater than expected, considering the constant vigilance of captains and mates. Of these, however, only a small percentage are able to land. Most of them are discovered and returned before the ship drops her pilot on the other side.

Sometimes, the hold reveals a pitiful tragedy when the vessel discharges its cargo. If a stowaway hides himself among the bales and boxes below, and the ship encounters rough weather, the pitching and tossing shifts the pieces of freight, and the secret passenger is crushed to death or entrapped among the huge piles or dies of starvation if the voyage is a protracted one.

Such an unfortunate was discovered in the hold of the S. S. Maryland last winter when she docked in Philadelphia after a stormy passage, and an emaciated corpse half devoured by rats was taken out with the cargo.

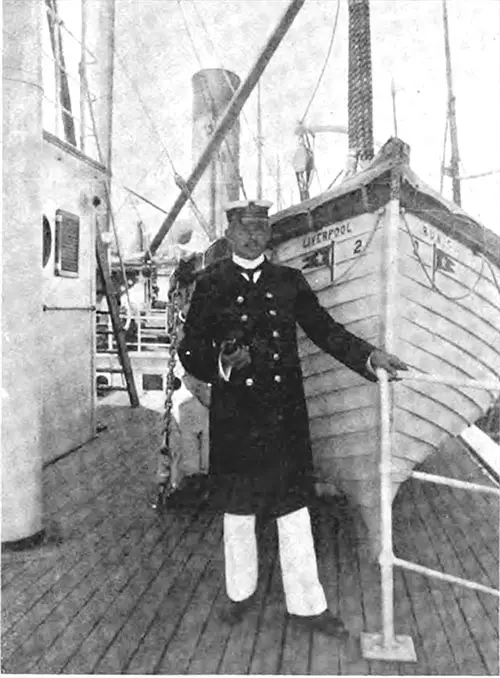

The Stowaway's Favorite Hiding Place - One of the Ships Lifeboats. The New Age, March 1906. | GGA Image ID # 14b1a1a877

An intelligent stowaway who fully understands the risks he runs watches for an opportunity. He tucks himself away in a lifeboat, where he finds water, provisions, and pure air. At the same time, the boat's jacket protects him from sun and rain. At night, he can come out of his snug retreat and stretch his legs with the stokers or the steerage passengers without much fear of detection.

The lifeboats are supposed to be overhauled and re-stocked with fresh bread and water on every voyage. Still, this duty is often omitted on a busy ship like an Atlantic liner. So, the stowaway's chances of discovery are lower than any other place on board. But in winter, when the freezing spray dashes high over the bulwarks and deck fittings and ventilators are crusted with ice, a berth in a lifeboat has some undeniable drawbacks.

Occasionally, one of these salt-water tramps hides in the narrow spaces between the boilers and is roasted alive before he can escape from his fiery prison.

Many stowaways crawl into the coal bunkers, where they are soon discovered, hauled out, and made to feel that the way of the transgressor is brutal at sea. Sometimes, the stokers take pity on one, bring him food and drink, and teach him how to take his airings after dark in the part of the ship where he is least likely to encounter an officer.

Often, the stowaway has friends in the steerage who conceal him. But he succeeds in evading the keen eyes of his mates during the voyage. In that case, there is not one chance in a thousand that he will be able to leave the ship undetected, and many ingenious are his devices to effect a landing.

An amusing instance was William Campbell, who dodged aboard the tramp steamship Hypatia at Liverpool and, on reaching New York, was ordered by the authorities to "move on" to the River Platte, the vessel's ultimate destination. But the stowaway longed to become a free American and had no intention of proceeding.

He was five feet seven inches tall, tipped the beam at one hundred and sixty-four pounds, was thick-shouldered and deep-chested, and the only way to liberty lay through a smooth iron bound port hole thirteen inches in diameter.

Nothing daunted, he stripped himself to the skin, and with the aid of the sympathetic cook who provided a bucket of slush with which he greased himself all over and a couple of friendly dockers to pull him by main force, he managed to squeeze through this narrow gate to freedom.

Another stowaway who tried it on another ship but neglected to grease himself stuck fast halfway through the port hole and had to be sawed out.

Johann Beck, A Plucky German Stowaway. The New Age, March 1906. | GGA Image ID # 14b1fb107e

A plucky stowaway was Johann Beck, the German house painter, who shipped himself in a box as freight on the S. S. La Patria from Hamburg and, after a sixteen-day voyage, arrived in New York more dead than alive. He found friends in this land of big hearts and could remain in the country he had suffered so much to reach.

Quite as courageous and even more persevering was Bozo Gacina, an Austrian boy sixteen years old. They left his native town of Dalmatia for Trieste, where he smuggled himself aboard a steamer. It took him to Alexandria, where he repeated the trick with the same success and reached Liverpool.

There, he stowed himself away for the third time on the Cunarder Umbria but, upon arriving in New York, was handed over to immigration officials, who deported him. Two weeks later, he was turned loose in Liverpool again.

But with perseverance worthy of a better cause, he hid himself on the Umbria for the second time, selecting for his stateroom the donkey engine used for distilling water; only the fact that the supply did not give out on the way over, and there was no necessity for starting up the boiler, saved the young adventurer from a horrible death. He was allowed to land.

The youngest stowaway on record was three-year-old Raffaleo Zaccarina on the Citta di Milano from Naples. A note addressed to Signora Zaccarina, New Haven, was pinned to his clothing: "I send you the boy as promised."

Little Berth Walman of Bermuda. One of the Youngest Stowaways. The New Age, March 1906. | GGA Image ID # 14b1d6b5d9

Occasionally, the extra passenger is a woman. Little Bertha Walman of Bermuda thought she would like to see New York and hid on the SS Pretoria. She was discovered on the way up and, despite her tears and lamentations, returned to the little white island of her birth.

The oldest stowaway in petticoats was a significantly aged French woman discovered in the steerage by the purser of La Lorraine when the ship was one day out from Havre. She was disabled, without clothes, without funds, and able to speak only the dialect of Brittany.

Though suffering from chronic hip disease, she had walked over two hundred miles from Cotes-du-Nard, Brittany, to Havre, and having no money, she depended on the charity of people along the road. The ship's officers treated her kindly and saw that she fared, as did the other steerage passengers who had paid their way, but she was deported.

A cool hand was a young man who partook of three meals daily, mingled freely with the passengers, slept in a berth on La Touraine, and was not discovered until the ship reached Ellis Island. He returned to France less luxuriously, being put to work with the stokers.

Two lads were found concealed between the bedding in the crew's quarters on the S. S. Servia just before the tug left her off the S. E. coast of Ireland. One was sent ashore, but the Captain was obliged to keep the other willy-nilly. Anticipating such a possibility, the shrewd rascal had stripped and thrown every rag of clothes overboard.

It was impossible to bring him on deck in the altogether and equally impossible to find clothes for him before the tug's departure, so he was carried to New York and back to his great delight.

A war-time stowaway was the Spanish lad Pedro Urizar, who concealed himself on the Spanish warship Reina Mercedes when she left Bilboa for Cuba and who became Admiral Cervera's cabin boy.

When the Spanish fleet was destroyed, he was rescued by the crew of Texas and brought to New York, where he elected to remain when peace was declared and the other prisoners were exchanged.

A homesick and penniless French man begged the French Consul at Colon, C. A., to send him home. This, however, the Consul had no power to do. "But," he said, "I can send you to Point-a-Pitre (Gaudaloupe)."

The man embarked for Point-a-Pitre, but when the ship was about to leave that place for Havre, he could not be found, though a thorough search was made for him, and it was sure that he had not gone ashore. A few miles outside the harbor, he appeared before the astonished Captain. "Where were you hidden that you could not be found before we sailed?" demanded the irate commander.

The homesick one pointed to one of the empty flour barrels the baker had put on the deck. These barrels are always thrown over the side when the vessel is clear of the harbor.

"I was there," he said, "your men looked among them but not into them." The French Captain, struck by the man's ingenuity, sent him to work with the coal trimmers and allowed him to leave the ship unmolested at Havre.

The S. S. Origaba was known to have a stowaway on board when leaving Vera Cruz. Still, he could not be found, even after every square foot of space was systematically searched from stem to stern.

Even the cargo was moved and inspected. Before leaving the next port, a fever port, the ship was fumigated to guard against possible infection. The stifling sulfur fumes smoked out Mr. Stowaway. Still, neither threats nor persuasions could induce him to reveal his hiding place.

Sometimes, the masters of sailing ships, generally short-handed, are not sorry to find two or three stowaways aboard to swell the crew at no extra expense to the owners.

Once in a while, though, a stowaway will not work, as was the case with a Spaniard from Barcelona, who concealed himself in a lifeboat on a French liner bound from Marseilles to Rio de Janeiro. When discovered, he took it very coolly and refused to go when ordered forward with the coal-passers. "I will not work," he said haughtily to the wraith Captain, "and you will take me to Brazil."

He was put in irons on the way and lodged in jail at Rio, but evidently, he well understood the law's delay in South America and had laid his plans accordingly. The ship was obliged to sail before his case came into court, and as the Captain was not there to press the complaint, he was allowed to go.

In extreme cases, the ship's officers may sympathize with a stowaway and make no special effort to rout him out before the vessel is beyond the harbor.

The officers and crew of a British tramp discharging coal at Puerta Barrios, Guatemala, took compassion on the wretched negroes on the dock who toiled all day in a tropic sun receiving in return only the blows, kicks, and curses of a brutal master.

When the steamer sailed, she carried twenty-six stowaways, not one of whom was seen out of his hiding place during the forty-eight-hour run to Vera Cruz. At that port, they were routed out and went ashore quite happily.

On a steamer plying between Alexandria and Liverpool, two little Arabs of the donkey-boy type were found concealed in a lifeboat when the ship was well on its way to England. When marched before the Captain, they offered the naive excuse that they had fallen asleep on board and did not awaken until they were far out at sea.

They were put to work with the coal trimmers, and I fear the good-natured Captain was looking the other way when the ship reached her dock in the Mersey, for they disappeared as soon as the gangplank was out.

Ten days later, on the outward passage, one of the little fellows turned up again, a grotesque figure attired in the red tunic of an infantryman but wearing his native fez or trebuchet. Trebuchet, in a great show of anger, the Captain asked him why he was not satisfied to stay in Liverpool.

"Ah! No, like Alexandria," said the swarthy rascal, gesticulating grimy hands and rolling sparkling black eyes. When I lay down in the street to sleep at night, a great man comes along with silver buttons on. He kicks me and says, "Move on there!"

A tragic fate was that of the boy Morris Zucker of New York, who stowed away on the steamer Levington, who was discovered and handcuffed but jumped overboard on reaching Savannah and drowned. Strangely enough, his body did not rise until Lexington's next arrival, when it came up alongside in the very spot where it had gone down.

The British Colonies get their share of stowaways, as do Americans. The Captain of a large sailing ship bound from Liverpool to Sydney, N. S. W., told me that he rooted out no less than seventeen stowaways of all ages and descriptions from different holes and corners of his vessel on the last voyage.

Each repeated the same hard luck story of no work, starvation, and the hope of bettering themselves in the Colonies. In the days of stately sailing ships when a glamor of romance hung over the sea, the unwelcome passenger was usually a lad who wanted to be a sailor.

The Captain of one of the Hamburg American liners took his first voyage as a stowaway. But the modern steamship stowaway is of a different mold. Men who have been doing Europe and gone broke in the process, prodigal sons returning penniless to the parental roof, and human derelicts drifting about from country to country with the wanderlust strong within them but no means to gratify it except by beating their way from port to port.

These are the general types of a class in which the steamship companies find a greater tax every year. Landing stowaways before the English coast is quitted has become an everyday occurrence on all the large steamers, especially the cargo boats. If the pilot has been dropped, it is a complex and often dangerous bit of work to put him near enough to the English coast to lower a boat and send him ashore.

The engines must be stopped, and valuable time must be lost, while there is always more or less danger of drifting on the rocks that girdle the British Isles. The Phenix liner St. Andrew, Antwerp to New York, struck a ledge off Shanklin, Isle of Wight, while approaching shore to remove ten stowaways and sustained severe damage.

The stowaway shrewd enough to hide himself until it is too late to land him costs the owners a pretty penny a hundred dollars and perhaps more if he gives them the slip on arriving out, and three or four of them every voyage is a heavy addition to the annual expense of any line.

If he happens to be an American citizen, he is free to walk down the gangplank as soon as the ship touches a United States port, but if he is an alien and the Captain, through carelessness or otherwise, allows him to land, the vessel is liable to a fine of $500.

In England, this troublesome tramp of the seas can be imprisoned for six months but usually gets only fourteen days, so this law does not abate the nuisance at all, as the ordinary stowaway is from a class familiar with jails and quite ready to risk "doing time" in his efforts to reach fresh fields and pastures new on the hither side of the Atlantic.

The stowaway discovered too late to be landed is likely to receive anything but gentle treatment from the wrathful Captain, who desires not only to punish him but also to discourage others from following his example.

The hardest, roughest work aboard is the stowaway's portion. He is generally put to work shoveling coal, a back-breaking, never-ending task on a trans-Atlantic liner. However, if the Captain is a tender-hearted man, and the case one that appeals to his sympathies, he may only put him to washing down decks.

This was the task allotted to a New York war correspondent who found himself stranded and penniless in the streets of Liverpool at the end of the Boer war and stowed away on a big White Star steamer.

The ship's officers saw that he fared a little better than the average stowaway. He worked faithfully across the country, getting home at any cost through manual labor.

An Impudent Stowaway. The New Age, March 1906. | GGA Image ID # 14b20433e3

Before the ship sailed again, he came down to the pier in fashionable attire and was royally entertained by his mates. It was hard to believe the well-groomed young gentleman in faultless tweeds was the same ragged, grimy, and disreputable-looking wretch who was yanked out of a lifeboat by the third mate. It led with no gentle hand to the captain, being treated to a running fire of choice expletives.

On this same vessel, another stowaway was a man of education who once managed one of the largest stock-broking firms in New York. Yet, another had been chief draughtsman in a Paterson, N. J., Engine Works. Both had come down through drink.

But the sentimental side of the stowaway has ceased to exist, and he is now a distinct source of annoyance, trouble, and expense to all concerned. It is almost impossible to prevent his coming aboard.

Stowaways have been known to live ten days on a ship before it sailed, as there is always a great deal of confusion on a steamer in port, people constantly coming and going, and always changes in the crew of stokers and coal-passers, so it is easy for the officers to think that a strange face belongs to a new hand.

Penalties vary between countries, but everywhere, they fall heaviest on the shipmaster. In a U.S. port, the culprit must be placed under special surveillance during the vessel's stay.

The cost of all this care must come out of the captain's pocket. Still, the payment of fifty or seventy-five dollars does not cover the extent of his responsibility for a heavy fine, which must also be paid if the stowaway escapes.

Vessels trading to Venezuelan and Colombian ports find it impossible to sail without many of these undesirable passengers, as they come aboard under the pretense of selling fruit or birds and hawk their wares about the decks until they find an opportunity to conceal themselves.

The Brazilian government has found it necessary to make a stringent law for stowaways. However, it must be confessed that it does little good. The nuisance has steadily increased in recent years, and British ship-owners and captains are now petitioning the authorities to deal more severely with stowaways.

Leaving the cost of his passage and probable fines out of consideration, his uninvited presence, especially on the mail boats, causes delay prejudicial to everyone interested in the vessel or the voyage except himself, who pays the passage of emigrants, but the Argentine Republic.

Minna Irving, "A Human Derelict – The Stowaway," in The New Age Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 3, March 1906, p. 216-221

Recap and Summary of "A Human Derelict—The Stowaway (1906)" 🚢🔎🕵️

This intriguing article explores the world of stowaways in the early 20th century, revealing their motivations, survival tactics, tragic fates, and the consequences for ship captains and authorities. The detailed stories range from daring escapes to horrifying deaths, illustrating the perils and persistence of stowaways who sought passage across the world without paying.

The narrative covers various stowaway experiences, from runaway children and war refugees to failed businessmen and thrill-seekers. Some were lucky enough to land permanent residency, while others were returned, punished, or even killed due to the dangers of hiding on ships.

Relevance to Ocean Travel and Historical Significance 🌊🚢

This historical account of stowaways is particularly valuable for:

Teachers & Students 📚 – Provides real-life examples of early 20th-century migration challenges, maritime law, and social class struggles.

Genealogists 🧬 – Highlights hidden immigration stories, especially for those who had ancestors who may have entered countries illegally via ship.

Historians 🏛️ – Explores the evolution of transatlantic travel, immigration restrictions, and the dangers of illegal sea travel.

Maritime Enthusiasts ⚓ – Details how stowaways survived aboard steamships, their hiding places, and the consequences for ship crews.

Most Engaging Content ✨

🔹 The Deadly Cost of Stowing Away 💀 – Some stowaways met gruesome fates, including one crushed in a chain locker, another roasted alive near the boiler, and one who suffocated in the ship’s cargo hold. These stories highlight the immense risks taken by those who sought free passage.

🔹 The "Greased Escape" Through a Porthole 🚪 – A daring stowaway in Liverpool greased himself with kitchen slush and squeezed through a 13-inch porthole to freedom, with crew members pulling him through. Another got stuck mid-way and had to be sawed out!

🔹 Children and Women Among the Stowaways 👩👦 – Some young children and women attempted to stow away, including a three-year-old boy sent to America with a note pinned to his clothing and an elderly French woman with a hip disease who walked 200 miles to board a ship illegally.

🔹 The German Painter Who Survived in a Box 🎨 – Johann Beck, a German house painter, hid inside a freight box on a ship for 16 days, nearly starving to death, but managed to stay in America after arrival.

🔹 The Unrepentant Stowaway 😏 – A Spaniard refused to work after being discovered aboard a ship, arrogantly declaring, “I will not work, and you will take me to Brazil.” The crew imprisoned him and later had him jailed in Rio.

🔹 Stowaways Who Became Soldiers or Officials 🎖️ – Some stowaways were absorbed into their new countries, including a Spanish boy who became a warship’s cabin boy and a former stockbroker who reinvented himself after reaching America.

🔹 Ship Captains' Struggles with Stowaways ⛴️ – Many captains had no legal authority to punish stowaways but were liable for heavy fines if they allowed them to land illegally. One ship suffered severe damage while trying to drop off ten stowaways, proving how costly the problem had become.

Noteworthy Images 🖼️

📷 "The Stowaway’s Favorite Hiding Place—One of the Ship’s Lifeboats

Shows how some stowaways evaded capture by hiding in lifeboats, an ingenious yet dangerous tactic, especially in stormy weather.

📷 "Johann Beck, A Plucky German Stowaway.

Highlights the resilience and determination of stowaways, such as Beck, who risked his life inside a shipping crate for a chance at a better life.

📷 "Little Bertha Walman of Bermuda—One of the Youngest Stowaways

Depicts how even children attempted to stow away, adding an emotional layer to the stories.

📷 "An Impudent Stowaway.

This suggests some stowaways were defiant and confident, viewing their actions as adventurous rather than illegal.

This riveting collection of real-life stowaway tales offers a thrilling look at maritime history, human desperation, and the extremes people would go to for a new life. 🚢🔍📜