Roer to Rhine: YANK Magazine’s Gritty WWII Combat Report – 6 April 1945

By SGT Ralph G. Martin, YANK Staff Correspondent

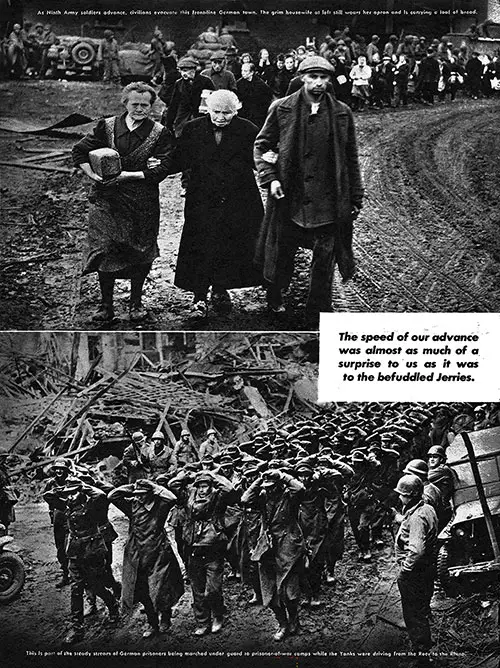

Roer to Rhine: The Speed of Our Advance Was Almost as Much of a Surprise to Us as It Was to the Befuddled German Prisoners-Of-War. (Yank, 6 April 1945, p. 2) | GGA Image ID # 234b923f4e. Click to View a Larger Image.

📘 Review & Summary: “Roer to Rhine” – A WWII Combat Correspondent’s Frontline Report

By Sgt. Ralph G. Martin – YANK, The Army Weekly – 6 April 1945

✍️ Overview & Historical Relevance

Sgt. Ralph G. Martin’s gritty dispatch from the frontlines during the U.S. Ninth Army’s rapid advance from the Roer to the Rhine is both riveting and unfiltered. This YANK Magazine article captures a crucial, transitional moment in WWII as American forces pushed deep into German territory, leading to the collapse of Nazi resistance in the West.

For teachers, students (13+), genealogists, military historians, and families of veterans, this article is an exceptional primary source. It offers direct insight into:

- The pace and intensity of U.S. armored operations in 1945.

- The confusion and collapse of German forces.

- The realities of occupation and liberated civilians.

- Combat fatigue, humor, irony, and the mindset of U.S. troops.

It also functions as a snapshot of war reporting styles during WWII—blunt, evocative, and full of soldier vernacular, which itself is historically and culturally informative.

With the Ninth Army at the Rhine—In a comfortable-looking living room, dirty, bearded doughfeet were puffing on liberated German cigars, discussing interesting characteristics of the different women of the world. Stretched out on a sofa, the platoon sergeant was talking on the telephone.

"Listen, sister," he said, "this is a very damned important call. I have a personal message from the citizens of the Bronx to Der Führer himself. Ring him again. I don't care how busy he is."

Everyone in the room temporarily forgot the conversation about women and gathered around the sergeant. The sergeant put the receiver in the center of the group so that all could hear the excited German guttural of the telephone operator.

When they finally stopped laughing, the sergeant said, "I guess they still don't know we took this town."

The Ninth Army sweep from the Roer to the Rhine was so fast that the Germans didn't know where we were coming from or where we were going or even where we were.

As for us, it was like a fever. The speed of it even excited some of the battle-weary boys—cartoonist Bill Mauldin's fugitives from the law of averages.

To the different guys, it was the St. Lo breakout, the push-up southern France, the race to Rome, the smash across Sicily, and the final phase of the Tunisian campaign.

They were all talking like this: "Well, maybe this is it. Let's meet the Russians in Berlin next week. We'll all be home in a couple of months. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

In the cellar underneath the rubble of Roerich, the general stared at a map, his face shining like a bridegroom's on his wedding night.

"Look where they are now," he said, pointing to a mark on the map. "Hell, they're 12 miles in front of the front."

He was talking about Task Force Church of the 84th Division, made up of beaucoup tanks and truck-loaded troops. At 0700 that morning, they took off and just kept going. Whenever they bumped into any SP fire from either flank, they detrucked some troops, detoured some tanks to mop up, and continued to move forward as fast as they could.

Now, only four hours later, they were away in front of everybody. On the map, their push looked like a skinny, long finger.

Before the day was over, the skinny finger had reached out and captured a rear-echelon German repple depple complete with staff, personnel, and more than 100 replacements. Poking around the German rear, the finger also grabbed a whole enemy field-artillery battalion, intact.

The most indignant of all the German artillery officers was the paymaster. "It isn't fair," he protested in German. "You were not supposed to capture me. This wasn't supposed to be a front." But the front was everywhere. It was sprawling like a fresh ink blot. As soon as the Germans tried to rush reserves to one sore spot, we would bust out somewhere else. Then the whole front almost completely disintegrated into space.

"I am going nuts here," said an arm-waving MP at the crossroads. "Everybody asks me where this outfit is and where that outfit is. Hell. I don't even know where my own outfit is. One of thTe boys just passed through this morning and said they were moving, and he didn't know where." Then he told about a buddy of his who had it even tougher. He was assigned to a guard yard filled with several hundred PWs; then, suddenly, the detachment received orders to withdraw, and they forgot all about this guy. Later that afternoon, the tired, worried, hungry MP approached Capt. Horace Sutton of New York, N. Y., and the 102d Division, and said: "Look, Captain. I don't know where my outfit is. I don't know if I am getting any relief. And I don't know what to do with all these prisoners. Can you help me?"

Prisoners poured in from everywhere. Long convoys of trucks were packed with them. Hundreds of others walked back, carrying their own wounded. Occasionally, a column of forward-marching Yanks would pass by a backward-marching column of [captured German soldiers]. Sometimes there would be a stirring silence. But every once in a while, you could hear the doughfeet talk it up:

"Jeez, some of them are babies, just lousy babies."

"Why don't you goose-step now, you [enemy troops]."

"And to think that they may send some of those bastards back to the States. Why don't they keep them here? There are plenty of cities to rebuild."

"Just what is your opinion now of the general world situation, Mr. Kraut?"

Almost 3,500 refugees from around the world are crowded together in the vast courtyard in Erkelenz. All of them had been doing slave labor of one kind or another for the Germans.

"You are now under the supervision of the American Military Government," said Eugene Hugo of St. Louis, Mo. "We will feed you and take care of you until we can get you back to your native country."

He made his explanation in English and then translated it into French, German, and Russian. The refugees just stood there entranced, as if they were listening to some great, wonderful music. Finally, one Russian woman broke out hysterically, sobbing, "We have been waiting for this for four years. For four years. . . ."

Erkelenz had been taken only that morning, but it was already so rear echelon that the only outfits in town by night were some Quartermaster and service troops. Some QM boys were wandering around in and out of cellars of some of the houses, hunting for liquid refreshment that might have been overlooked, when they stumbled onto a basement full of Germans. Sitting right next to the Jerries was a pile of unused hand grenades.

The kidneys of the Quartermaster boys almost started functioning again then and there. Still, the Germans only wanted to be friends. They explained that they had tried to surrender all day long, but nobody wanted to stop long enough to pick them up. So they came down to this cellar, waiting impatiently for somebody to come downstairs so that they could surrender and get something to eat.

They couldn't understand it. Why were the Americans in such a hurry?

It wasn't a breeze everywhere. There were plenty of spots where the Krauts decided to stay put until they were kaput. There was this flat, 5,000-yard-long field partially surrounded by a semicircle of thick woods. Planted in the woods were a dozen AT guns, plus some liberally scattered SP guns, machine-gun nests, and tanks. The guns were all pointed, waiting and ready for the American armor to try to get through.

G-2 of the 5th Armored knew what the score was, but alternative detours would take too much time. A slow, slugging battle would be too expensive in the long run, and besides, these enemy guns had to be knocked out anyway. So the tank boys just raced across the field at full speed, their weapons firing. Not all the tanks made it. Some got hit on the run; others bogged down in the mud and sat like dead ducks until the German AT guns picked them apart and burned them up.

When the show was over, after the last tank had swept past the field, there were no more AT guns in operation, no more SP guns or enemy tanks either. The 5th Armored boys also shot up two American light tanks, which the Germans were using minus the USA insignia.

Frenchmen walked down the road, wearing their blue berets and their neat, frayed pants. There had been a strict shortage of MPs, so much so that one MP was often detailed to bring back 300 prisoners all by himself. When these ex-French soldiers volunteered their services, all of them were given K-rations and deputized as corrections officers. You could see satisfied expressions on their faces when they prodded the Germans to walk a little faster.

"It is nice to have a gun pointed the other way," one of them said in French.

There was a lot of cheek-kissing, French style, when the XIII Corps liaison officer, Capt. George Kaminski spotted one of the incoming French refugees. The two of them had been in the same place and in the same Infantry company four years before. Now, the liaison officer informed the refugee about their mutual acquaintances. This one was wounded and is running a perfume shop in Paris; this other one is down in Colmar; somebody else is dead.

Before the Roer jump-off, our troops had found just as many dead Germans as live ones in these tiny, rubble-filled towns. But Muenchen-Gladbach was different. It was full of live Germans, estimated at 75,000. And practically all of them were trying to butter us up and sneak inside our sympathies. Especially the women, who felt their favors were worth bartering for food.

"[German] officers had their own women living here with them," said Capt. Bennett Pollard of Baltimore, Md., at the CP of the 1st Battalion, 175th Regiment of the 29th Division. The CP was a complicated network of hallways and cellars, with triple-decker steel beds for the enlisted men and separate rooms for the officers.

The German CO had a private blonde, who was still there when the troops came into the city during the night. Capt. Pollard held up a flimsy nightgown that he had found on the German Soldier's bed. "I guess we really surprised them all right," he said.

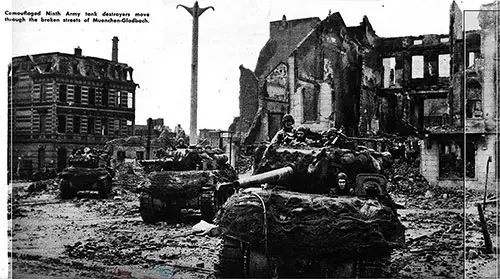

Camouflaged Ninth Army Tank Destroyers Move Through the Broken Streets of Muenchen-Gladbach. (Yank, 6 April 1945: 3) | GGA Image ID # 234ba427c5

The captain told how absolutely still it was when they marched in, how they heard nothing except their marching.

There had been no sniping, and the only isolated case of enemy activity was the report of two teller mines being placed on tank treads on the roads during the night. They had been discovered in time.

Everything was smooth and easy so far. Too smooth, he said.

There was nothing smooth about the push into S, which sits smack on the Rhine, just opposite Düsseldorf. The Germans had built a big trench along the railroad tracks, and they studded it with their small, accurate mortars and fast-firing machine guns. After considerable artillery preparation, the doggies of Able, Baker, and Charley Companies of the 1st Battalion, 329th Regiment of the 83d Division, finally swept through it at 0300 with marching fire. They just walked in and kept shooting.

They kept shooting even when they came down the Neuss main street because the houses were with snipers. Within the next few hours, some of the Germans ran into the cellars and were burrowed out by hand grenades; some of them just continued firing all day long, killing some doughs, and then, when they ran out of ammo, came out smiling cheerfully, ready to surrender. Some of these Volksturm boys just conned the situation, stopped shooting, took the Volksturm armbands off their civilian clothes, and ran outside with bottles of cognac to greet the American liberators.

“We caught a couple of those bastards in the act,” said the Battalion CO, Lt. Col. Tim Cook of Snyder, Tex. “I had a tough time trying to stop my boys from shooting the whole bunch of them.

‘These people seem to think that if they take down their Third Reich flags and scratch out Hitler’s face on the big portrait on the wall of their front parlor, they’re automatically anti-German and our bosom buddies. I don’t trust any of these bastards.”

The first day in Neuss was typical of a whole week’s war.

Civilians were strutting around town, not paying any attention to snipers’ bullets, well knowing that they weren’t targets. Shells were dropping in the town’s outskirts, near the river, only a few blocks away, and every once in a while, the soldiers around the city square would look around for doorways to run into. But most of the guys didn’t seem to be worried too much. A few of them were tinkering with a nonworking, deserted civilian auto. Several dozen others were riding around on bicycles. Some even wore top hats.

If you wanted to see the Rhine River and Düsseldorf, you had to go to the noisy, unhealthy part of town and climb to the top of one of the significant buildings.

Somebody told us where a good spot was— two blocks down, turn right. You can’t miss it.

A window in the top-floor toilet was the 3rd Battalion OP. From there, you could not only see Düsseldorf and the big bridge over the Rhine, but you could also see the war almost as clearly as if it were a play and you were sitting in the eighth row center.

You could see the Krauts dug in for a last-ditch stand in front of the bridge (which was scheduled to be blown up soon), and you could see our guys ducking and running and falling flat. And you could see mortar fire falling among them. During all this, on the floor below us, some older women were scrubbing floors, occasionally staring at the visitors—American soldiers with expressionless faces.

Back at the center of the town, sitting behind a heavy machine gun, Pfc. John Becraft of Brooklyn, N. Y., and C Company didn’t seem to give much of a damn about the Rhine.

“I’d rather see the Hudson,” he said.

🎯 Noteworthy Content & Why It Engages Readers

🔥 Most Compelling Sections:

The "telephone call to Hitler" anecdote delivers humor amid chaos, revealing soldier morale and gallows humor.

Task Force Church’s rapid armored advance is described in exciting detail, showcasing the daring speed and improvisation of U.S. tank operations.

POWs and civilians’ reactions add a powerful human dimension to the campaign, particularly the scenes of Russian and French forced laborers weeping with joy upon liberation.

The detailed encounter in Neuss, with its trench warfare, snipers, and deceptive civilian surrender, is a microcosm of the fog of war.

📷 Highlighted Images

🖼️ Image: 📌 Caption Summary

Roer to Rhine Frontline: “Speed of our advance was as surprising to us as to POWs” — Emphasizes shock and momentum.

Burned-Out Tank & Düsseldorf View: Illustrates destruction and the vast scale of the Allied push.

Muenchen-Gladbach: Camouflaged U.S. tank destroyers navigating rubble — stark visualization of urban warfare.

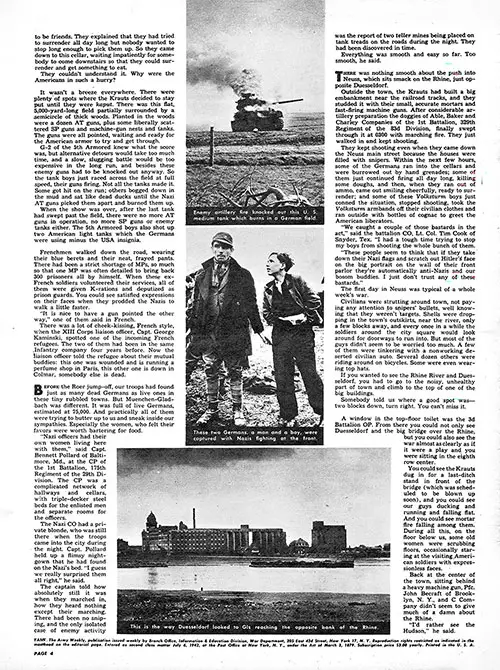

Captured Germans (Man & Boy): Raises ethical and emotional questions about youth in combat.

“Rhine-to-Hudson” Quote: Powerful close that humanizes the soldier’s longing for home.

🔎 Mini Dictionary of Uncommon Terms

Term: Definition

Doughfeet: Slang for U.S. infantry soldiers (aka “doughboys”).

SP guns: Self-propelled guns—artillery mounted on a vehicle.

Repple Depple: Replacement depot for processing new troops.

AT guns: Anti-tank guns.

Volksturm: German home defense militia, often older men and boys.

OP: Observation Post.

K-Rations: Compact field food rations for U.S. soldiers.

🎓 Educator’s Note

📚 For Classroom Use:

This article is a powerful teaching tool on the human experience of war. It provides:

- Authentic soldier perspectives.

- Real-world WWII geography and military operations.

- Ethical dilemmas about occupation, POW treatment, and civilian behavior during wartime.

💡 Encourage students to contrast this narrative with textbooks to explore tone, bias, and narrative style in primary sources.

📢 Final Thoughts

The Roer to Rhine article from YANK, The Army Weekly offers an unvarnished look at the final Allied offensives in WWII. It blends journalism with soldier storytelling, revealing both strategic movements and raw human emotion. Preserving this article within the GG Archives enhances public access to WWII history and offers an excellent foundation for critical thinking, military research, and intergenerational storytelling.

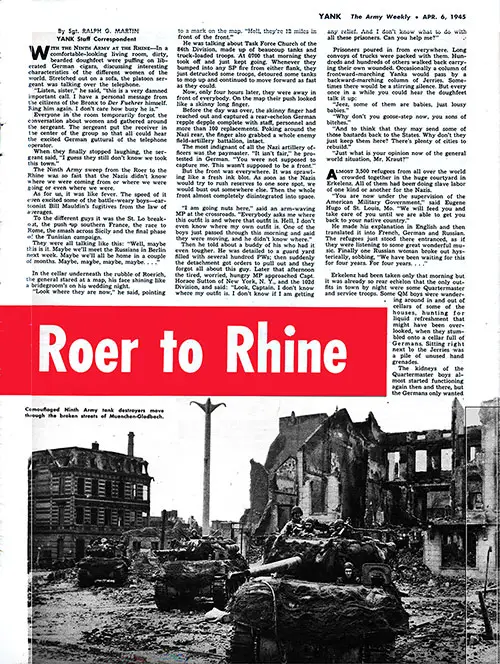

"Roer to Rhine," Article by Yank Staff Corresponden SGT Ralph G. Martin, Page 3. (Yank, 6 April 1945: 3) | GGA Image ID # 234bb076b5. Click to View a Larger Image.

"Roer to Rhine," Page 4. Photos Include: (Top) Enemy Artillery Fire Knocked Out This US Medium Tank Which Burns in a German Field; (Middle) Captured: A German Soldier and a Youth Who Had Been Forced Into Combat—Highlighting the Desperate State of German Resistance.; and (Bottom) This is the Way Duesseldorf Looked to GIs Reaching the Opposite Bank of the Rhine. (Yank, 6 April 1945: 4) | GGA Image ID # 234bc50586. Click to View a Larger Image.

Magazines on or about the United States Army, Their Personnel, Training Camps, Actions and Institutions

GG Archives

Yank Magazine - 1945-04-06

- Roer to RhineBy Sgt. Ralph G. Martin

- IWO:D+8 By Sgt. Bill Reed

- Yanks at Home and Abroad

- Why Ain'.t They in Uniform By CpI. Hyman Goldberg

- 10th Mountain Division By Cpl. George Barrett

- Burma Hermits By Sgt. Walter Peters

- People On The Home Front By Pfc. Debs Myers

- The Reconversion of Sgt. McDougall By S/Sgt. Gordon Crowe

- Scenes On A World War II Era Aircraft Carrier - The Flat-Top

- Cindy Garner YANK Pin-up Girl

- Army Camp News - April 1945

YANK Magazine - 1945-04-27

- Navy On The Rhine By Sgt. Ed Cunningham

- Yanks at Home and Abroad

- Women Who Want To Go Abroad

- Bankers Hours By Sgt. Ozzie St. George

- Hollywood, California and World War II

- Army Camp News - 27 April 1945

- The Shooting at Aachen - Franz Oppenhof

- The Battett - Return on Rotation

- Sports During the War?

- Jinx Falkenburg - YANK Pin-up Girl

- Seeing Paris - GI Tourists in April 1945

- Behind The Japanese Lines on Luzon

ArmyDigest - 1963-12

Other Army Sections

Primary Military Collections