Spanish Influenza Bulletin - 1918

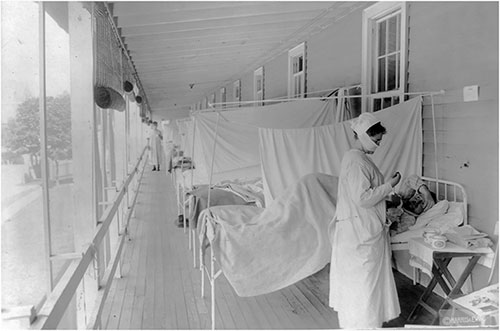

Nurse Taking Patient's Pulse at Influenza ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Wash., DC. Photo by Harris & Ewing ca. 1 November 1918. Library of Congress # 2016648028. GGA Image ID # 1501d60006

The superintendents of hospitals are apparently in doubt as to the proper attitude to assume with reference to accommodating persons suffering from influenza.

A number of them are under the impression that unless they provide an isolation ward or isolation rooms, they will not be permitted by the regulations of the Department of Health to care for these cases.

If the prevalence of influenza increases to any degree, it will he manifestly impossible to provide hospital care for any considerable proportion of the cases, and the general hospitals will have to be depended upon to assist. The restrictions upon isolation of patients in hospitals should, therefore, not be severe.

A modified quarantine will he accepted by the Department of Health in institutions. In other words, their patients may be kept in the general ward but separated from pneumonia cases so as to avoid the danger of super adding a pneumococcus or other bacterial infection to the attack of influenza.

Moreover, ample space should be allowed between the beds and screens should be placed around the beds of patients suffering from influenza, so as to prevent the transmission of influenza to other ward patients through coughing, sneezing, or other means of contact.

It is of course assumed that nurses who care for influenza patients will be instructed in each institution to carefully wash their hands before coming in contact with other patients and that they will exercise due caution with regard to the destruction and care of discharges from the nose, mouth, throat, and respiratory system.

Suggestions as to the Diagnosis of So-Called Spanish Influenza

Without doubt, private physicians in increasing numbers will report not only cases in which they have made a definite diagnosis of influenza, but in which such diagnosis is difficult, and I am reasonably certain that they will make requests that diagnosticians of the bureau be sent to give aid in arriving at a conclusion.

I am, therefore, submitting a very brief sketch which is to serve as an aid to the diagnosticians, several of whom have requested information with reference to the diagnostic features of Spanish Influenza.

In our experience, the cases which have been seen thus far generally give a history of an attack of Coryza or acute bronchitis, which subsides in a few days, but is followed in about two or three weeks by the onset of the symptoms which have been commonly described as constituting the picture of Spanish Influenza.

In other words, it seems as if a special susceptibility is created by a previous attack of coryza or acute bronchitis. The onset of the attack is rather sudden without prodromal symptoms as a rule, and is characterized by fever of varying degree, marked headache, marked pains in the bones and joints, frequently by chillness, and is usually associated with coryza and acute bronchitis.

In many cases and particularly those of the severer type, the conjunctivae and the throat are somewhat injected. The headache marked pains in the back and joints, prostration and fever, constitute the chief and outstanding symptoms.

Anorexia is also present and in a number of instances the patient vomits at the onset of the disease, and this vomiting may be frequently repeated. In robust and well-nourished individuals, the attack is as a rule fairly mild and rapidly subsides after the second or third day, terminating in almost all instances after a duration of three or four days.

The picture, generally speaking, is the familiar one which has been presented year after year in the typical cases of influenza. The severer types of cases are generally observed in under-nourished persons who have been subject to considerable nervous and physical strain and have thus far been almost exclusively among persons who have arrived from foreign ports.

My attention has been called to a tendency on the part of several physicians to jump at conclusions that patients suffering from symptoms which have just been described are necessarily cases of influenza, when in reality a typical follicular exudate on the tonsils clearly showed that the symptoms are attributable to an ordinary attack of follicular tonsillitis.

It is timely, I believe, to warn against this possible error in diagnosis. A few cases have been observed in which the manifestations have been largely gastric, with vomiting as the prominent symptom; a number of cases on the other hand have been seen in which the attack seemed to concentrate itself upon the respiratory organs.

The large majority of cases ran mild courses and the tendency toward the development of bronchial pneumonia as a complication has been observed, so far as our experience goes, in only a relatively small number, and these as a rule were cases in which the patient was up and about and tried to fight off the attack.

To sum it all up. the diagnosticians must not expect to find a new symptom- complex and those who have in the past seen a large number of cases of influenza, will readily recognize the cases which seem now to the current.

It is desirable so far as practicable, to have cultures taken from the throat and the blood to isolate, if possible, the organism responsible for the disease. This step seems, however, to be futile if the case is seen after the first or second day.

"Spanish Influenza," and "Suggestions as to the Diagnosis of So-Called Spanish Influenza," in the Weekly Bulletin of the Department of Health, City of New York, New Series Vol. VII, No. 39, 28 September 1918, pp. 303-304.