Expert Medical Advice on Influenza - 1918

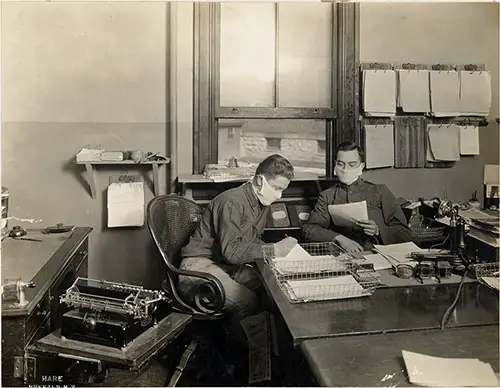

Spanish Influenza in Army Hospitals. In Hospital Number 4 at Fort Porter, New York, the Epidemic Was Guarded Against so Closely That Persons of the Office Force Used Masks at Work. Showing Dictation Being Giving Through the Masks. Photograph circa 19 November 1918. National Archives and Records Administration RG 165-WW-269B-33. NARA ID # 45499355. GGA Image ID # 150784d6e6

Disagreement Among Physicians at the recent Chicago meeting of the Public Health Association, regarding many important points in the character and treatment of influenza, is reported in the daily press.

Nevertheless a substantial agreement on some other points quite as vital appears clearly from a reading of the medical journals, and practical suggestions for the home-care of patients will be found in a statement issued by the British Royal College of Physicians, quoted at the end of this article.

Experts would seem to be at one in looking upon the present epidemic as simply a variety of a well-known disease prevalent, with occasional outbursts of violence, for hundreds of years.

They agree that it is a germ disease and that it is very contagious at close range, although probably not communicable through air, water, or material objects; that its danger consists largely in the likelihood that it will be accompanied or followed by a peculiarly virulent type of pneumonia, whose occurrence is favored by neglect or wrong treatment, and finally that not all persons are equally susceptible, those in weakened physical condition usually succumbing first.

Points still open to discussion are the reasons for epidemics in general and for this one in particular, the nature of the precise germ or group of germs responsible for it, and the efficiency of various forms of preventive and curative treatment, including quarantine, as generally practiced, inoculation with serum, the "influenza mask," and the use of various drugs.

Regarding the outbreak itself, whose world-wide character has earned it the name of "pandemic," the writer of a leading editorial in The Lancet (London, November 2) speaks as follows:

"If those who feel ill would stay at home, if those who are well would avoid traveling in railway-carriages with the windows closed, or in unventilated trams and busses; and, above all, if the public would forego picture-palaces or other crowded places of amusement so long as the epidemic continues, much would be done to limit the spread in populous centers."

The fact that the army camps have been excellent places to study the disease unaffected by local conditions makes a recent article by Dr. George A. Soper. Major U. S. A., one of the most interesting reports on its progress. Dr. Soper, writing from the Army's Division of Infectious Diseases and Laboratories in Washington to The Journal of the American Medical Association (Chicago, December 7), states his belief that "had it not been for the pneumonia, the pandemic would not have attracted much attention."

The disease has come in "waves," often with the violence of an explosion. He goes on:

"Within about a week after the outbreak of the influenza, there occurs an ominous prevalence of pneumonia. The pneumonia does not exist as a separate epidemic but is always a follower of influenza. How the two diseases are related is not positively known. It is clear that the influenza paves the way for the pneumonia, if it does not actually produce it."

Steps taken by the military authorities to combat the disease fall under three heads, and apparently any efforts elsewhere must also be similarly classified. Major Soper gives them as "isolation, sanitation, and education." These he briefly explains as follows:

"1. By isolation is meant any and all procedures by which infected could be separated from the susceptible persons. Included in this list were steps for the prevention of crowding, quarantine, head-to-foot sleeping, the separation of heads at mess, and the use of cubicles and masks.

"2. Under sanitation may be included the cleaning and airing of barracks and bedding, the oiling of floors to keep down the dust, the boiling of mess kits, and many other procedures.

"3. Education, always a predominant motive in the Army, was applied as never before to the prevention of disease among troops. The medical officers were taught what to expect in the way of symptoms and what principles of prevention to put into effect. The men were taught something of the principles of disease-transmission and how to carry out their part of the work of prevention."

As a result of these methods the disease "is already practically gone in most army camps." Much can be done in military camps, of course, that cannot be done in civil communities, but their example points the way.

It must be said that some physicians have doubted the permanent efficacy of any kind of quarantine measures and have pointed out that in New York, where they have been few, the disease, on the whole, has been less violent than in Boston, where, after the first outbreak, they were exceptionally strict.

Still, such measures have been chiefly relied on, although in different degree, by most American cities, and their necessity has not been widely questioned.

With regard to means of transmission, Dr. Soper is very clear.

He says:

"It is a fundamental assumption that influenza is produced when, and only when, material from the mouth or nose of infected persons gets into the mouth or nose of someone who is susceptible. As is plainly recognized in respect to intestinal infections, the hand probably plays an important part in the transmission of influenza. Coughing and sneezing help greatly to spread the infection.

"It has long been known that interchanges of bacteria occur commonly from mouth to mouth under ordinary conditions of social intercourse. Most of these organisms are harmless under normal conditions of health. That their capacity for harm is sometimes increased, sometimes reduced, according to various circumstances, is highly probable…

"The conditions that govern susceptibility to influenza are not understood. Good general health, absence of fatigue and of cold and hunger are methods of prevention which have long been advocated by many and which in spite of scientific criticism still have much to recommend them. Whatever conduces to low bodily tone is believed by most persons to favor infection.

Some, however, hold that specific immunity either does or does not exist, and that wet feet, insufficient bedding, chill, hunger, and fatigue have nothing to do with susceptibility.

"Vaccination against pneumonia is practicable; but such preventive treatment is in the experimental stage as respects influenza. As to natural immunity, one attack is believed to protect against another, and some people seem to be immune without ever having experienced an attack."

If "low bodily tone" conduces to the disease, as Dr. Soper thinks, evidently his second point— "sanitation"—is of vital importance. Municipal action in this direction is hardly notice able, owing to the stress placed on isolation.

Such attention as is paid to it is individual, under the advice of the medical profession. When we come to the third head, "education," we find that more is probably being done by public bodies than in any previous epidemic.

Leaflets have been scattered broadcast, through the medium of public and educational bodies, schools, public libraries, and associations of all kinds, to enlighten the public regarding the disease, its symptoms, and the methods of preventing and fighting it.

From the supplements to the United States Public Health Reports by Surgeon-General Rupert Blue, we quote the following paragraphs, which not only show the extent of these efforts at popular education, but will serve to give our readers some idea of the devices and methods approved by government experts.

General Blue Says

"It is very important that every person who becomes sick with influenza should go home at once and go to bed. This will help keep away dangerous complications and will, at the same time, keep the patient from scattering the disease far and wide. It is highly desirable that no one be allowed to sleep in the same room with the patient. In fact, no one but the nurse should be allowed in the room.

"If there are cough and sputum or running of the eyes and nose, care should be taken that all such discharges are collected on bits of gauze or rag or paper napkins and burned. If the patient complains of fever and headache, he should be given water to drink, a cold compress to the forehead, and a light sponge.

"Only such medicine should be given as is prescribed by the doctor. It is foolish to ask the druggist to prescribe and may be dangerous to take the so-called 'safe, sure, and harmless' remedies advertised by patent-medicine manufacturers.

"If the patient is so situated that he can be attended only by someone who must also look after others in the family, it is advisable that such attendant wear a wrapper, apron, or gown over the ordinary house clothes while in the sick-room, and slip this off when leaving to look after the others.

"Nurses and attendants will do well to guard against breathing in dangerous disease germs by wearing a simple fold of gauze or mask while near the patient…

"In guarding against disease of all kinds, it is important that the body be kept strong and able to fight off disease germs. This can be done by having a proper proportion of work, play, and rest, by keeping the body well clothed, and by eating sufficient, wholesome, and properly selected food. In connection with diet, it is well to remember that milk is one of the best all-around foods obtainable for adults as well as children.

"So far as a disease like influenza is concerned health authorities everywhere recognize the very close relation between its spread and overcrowded homes. While it is not always possible, especially in times like the present, to avoid such overcrowding, people should consider the health danger and make every effort to reduce the home overcrowding to a minimum. The value of fresh air through open windows cannot be overemphasized.

"Where crowding is unavoidable, as in streetcars, care should be taken to keep the face so turned as not to inhale directly the air breathed out by another person.

"It is especially important to beware of the person who coughs or sneezes without covering his mouth and nose. It also follows that one should keep out of crowds and study places as much as possible, keep homes, offices, and workshops well aired, spend some time out of doors each day, walk to work if at all practicable—in short, make an effort to breathe as much fresh air as possible."

A statement issued by the British Royal College of Physicians, and published in the London Times Weekly (November 15), declares that "this outbreak is essentially identical, both in itself and in its complications, including pneumonia, with that of 1890," and "has no relation to plague, as timely advice is given to the public:

"Well-ventilated, airy rooms promote well-being, and to that extent, at any rate, are inimical to infection; drafts are due to unskillful ventilation, and are harmful; chilling of the body surface should be prevented by wearing warm clothing out of doors.

"Good, nourishing food, and enough of it, is desirable; there is no virtue in more than this. Alcoholic excess invites disaster; within the limits of moderation each person will be wise to maintain unaltered whatever habit experience has proved to be most agreeable to his own health.

"The throat should be gargled every four to six hours, if possible, or, at least, morning and evening, with a disinfectant gargle, of which one of the most potent is a solution of twenty drops of liquor soda chlorinate in a tumbler of warm water.

"A solution of common table salt, one tea spoonful to the pint of warm water, is suitable for the nasal passage; pour a little into the hollowed palm of the hand and snuff up the nostrils two or three times a day.

"Since we are uncertain of the primary cause of influenza, no form of inoculation can be guaranteed to protect against the disease itself. From what we know as to the lack of enduring protection after an attack, it might in any case be assumed that no vaccine could protect for more than a short period.

"But the chief dangers of influenzas lie in its complications, and it is probable that much may be done to mitigate the severity of the affection and to diminish its mortality by raising the resistance of the body against the chief secondary infecting agents.

"No vaccines should be administered except under competent medical advice. No drug has as yet been proved to have any specific influence as a preventive of influenza. At the first feeling of illness or rise of temperature the patient should go to bed at once and summon his medical attendant.

"Relapses and complications are much less likely to occur if the patient goes to bed at once and remains there till all fever has gone for two or three days; much harm may be done by getting about too early.

"Chill and overexertion during convalescence are fruitful of evil consequences. The virus of influenza is very easily destroyed, and extensive measures of disinfection are not called for.

Expectoration should be received, when possible, in a glazed receptacle in which is a solution of chloride of lime. Discarded handkerchiefs should be immediately placed in disinfectant, or, if of paper, burned.

"The liability of the immediate attendants to infection may be materially diminished by avoiding inhalation of the patient's breath, and particularly when he is coughing, sneezing, or talking.

"A handkerchief should be held before the mouth, and the head turned aside during coughing or sneezing. The risk of conveyance of infection by the fingers must be constantly remembered, and the hands should be washed at once after contact with the patient or with mucus from the nose or throat.

"Each case must be treated, as occasion demands, under the direction of the medical attendant. No drug has as yet been proved to have any specific curative effect on influenza, though many are useful in guiding its course and mitigating its symptoms. In the uncertainty of our present knowledge considerable hesitation must be felt in advising vaccine treatment as a curative measure.

"A period of enfeeblement following an attack of influenza should never be disregarded, as it is apt to mask the presence of other morbid conditions."

"Expert Medical Advice on Influenza," in The Literary Digest, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, Vol. LIX, No. 13, Whole No. 1497, 28 December 1918, p. 23 & 117.